If you’ve followed debates in popular philosophical circles, you’ve surely heard the critique of “scientism,” the “view that only scientific claims are meaningful.” The term doesn’t apply only in defenses of religious explanations, but also of the arts and humanities—long imperiled by sweeping budget cuts and now seemingly upended by neuroscience.

We have the neuroscience of music, of literature, of painting, of creativity and imagination themselves…. What need anymore for those pedants and obscurantists in their ivory tower academic cubicles? Sweep them all away for better MRI machines and statistical programs! Who, gasp the opponents of scientism, would hold such a philistine view? Maybe only a straw man or two.

For those in the emerging field of “neuroaesthetics,” the goal is not to vivisect the arts, but to observe what art—however defined—does to the brain. Neuroaesthetics, notes the Washington Post video above, theorizes that “some of the answers to art’s mysteries can be found in the realm of science.” As University of Houston Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Jose Luis Contreras-Vidal puts it in the video below, “the more we understand the way the brain responds to the arts, the better we can understand ourselves.” Such understanding does not obviate the mystery of art as, the Post writes in an accompanying article, “the domain of the heart.”

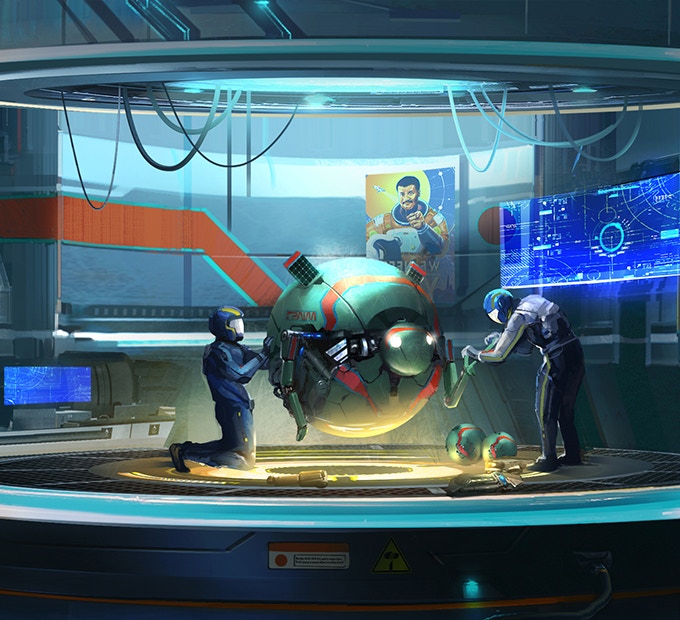

The spectacle of performing artists, writers, and musicians wearing skullcaps covered with wires while in the midst of their creative acts may look ludicrous to us layfolk. The University of Houston takes this research quite seriously, however, appointing three visual artists-in-residence to work alongside many others on Professor Contraras-Vidal’s ongoing neuroaesthetic projects, which also include dancers and musicians. In addition to studying artists’ brains, the NSF-funded project has recorded “electrical signals in the brains of 450 individuals as they engaged with the work of artist Dario Robleto in a public art installation.”

The Post summarizes some of the possible answers offered by this kind of research: arts such as dance and theater stimulate our desire to experience intense emotions together in a group as a form of social cohesion. Seeing live performances—and surely even films, though that particular art form is slighted in many of these accounts—triggers a “neural rush…. With our brain’s capacity for emotion and empathy, even in the wordless art of dance we can begin to discover meaning—and a story.” This brings us to the importance our brains place on narrative, on movement, the “logic of art” and much more.

For better or worse, neuroaesthetics is—at least at an institutional level—in some competition with those branches of philosophy classically concerned with aesthetics, though often the two endeavors are complementary. But using science to interpret art, or interpret the brain on art, should in no way put the arts in jeopardy. Serious scientific curiosity about the oldest and most universal of distinctively human activities might instead provide justification—or better yet, funding and public support—for the generous production of more public art.

Related Content:

How Information Overload Robs Us of Our Creativity: What the Scientific Research Shows

The Neuroscience of Drumming: Researchers Discover the Secrets of Drumming & The Human Brain

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness