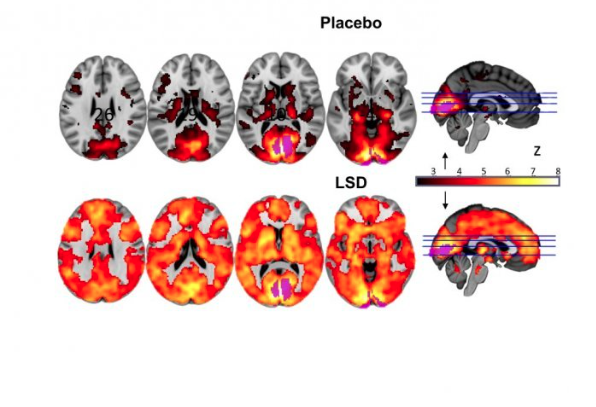

We’ve all had those moments of struggle to come up with le mot juste, in our native language or a foreign one. But when we look for a particular word, where exactly do we go to find it? Neuroscientists at Berkeley have made a fascinating start on answering that question by going in the other direction, mapping out which parts of the brain respond to the sound of certain words, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to watch the action on the cerebral cortices of people listening to The Moth Radio Hour — a popular storytelling podcast you yourself may have spent some time with, albeit under somewhat different circumstances.

“No single brain region holds one word or concept,” writes The Guardian’s Ian Sample on the “brain dictionary” thus developed by researcher Jack Gallant and his team. “A single brain spot is associated with a number of related words. And each single word lights up many different brain spots. Together they make up networks that represent the meanings of each word we use: life and love; death and taxes; clouds, Florida and bra. All light up their own networks.”

Sample quotes Alexander Huth, the first author on the study: “It is possible that this approach could be used to decode information about what words a person is hearing, reading, or possibly even thinking.” You can learn more about this promising research in the short video from Nature above, which shows how the team mapped out how, during those Moth listening sessions, “different bits of the brain responded to different kinds of words”: some regions lit up in response to those having to do with numbers, for instance, others in response to “social words,” and others in response to those indicating place.

You can also browse this brain dictionary yourself in 3D on the Gallant Lab’s web site, which lets you click on any part of the cortex and see a cluster of the words which generated the most activity there. The other neuroscientists quoted in the Guardian piece acknowledge both the thrilling (if slightly scary, in terms of thought-reading possibilities in the maybe-not-that-far-flung future) implications of the work as well as the huge amount of unknowns that remain. The response of the podcasting community has so far gone unrecorded, but surely they’d like to see the research extended in the direction of other linguistically intensive shows — Marc Maron’s WTF, perhaps.

via The Guardian

Related Content:

Free Online Psychology & Neuroscience Courses

Becoming Bilingual Can Give Your Brain a Boost: What Recent Research Has to Say

Steven Pinker Explains the Neuroscience of Swearing (NSFW)

This Is Your Brain on Jane Austen: The Neuroscience of Reading Great Literature

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.