The brainlessness and hypocrisy of television has long been a source of fun and social commentary in punk rock—from Black Flag’s “TV Party” (“I don’t even bother to use my brain anymore”) to the Dead Kennedys’ “M.T.V. –Get Off the Air” (“… feeding you endless doses / of sugar-coated mindless garbage”). It’s fitting then that one of the seminal moments in punk history happened on television, orchestrated by Sex Pistols manager and arch provocateur Malcolm McLaren, who knew as well as anyone how to manipulate the media. The notorious Bill Grundy interview, which you can watch—likely not for the first or even second time—above, rocketed the Sex Pistols to national infamy overnight, simply because of a few swear words and some slightly rude behavior.

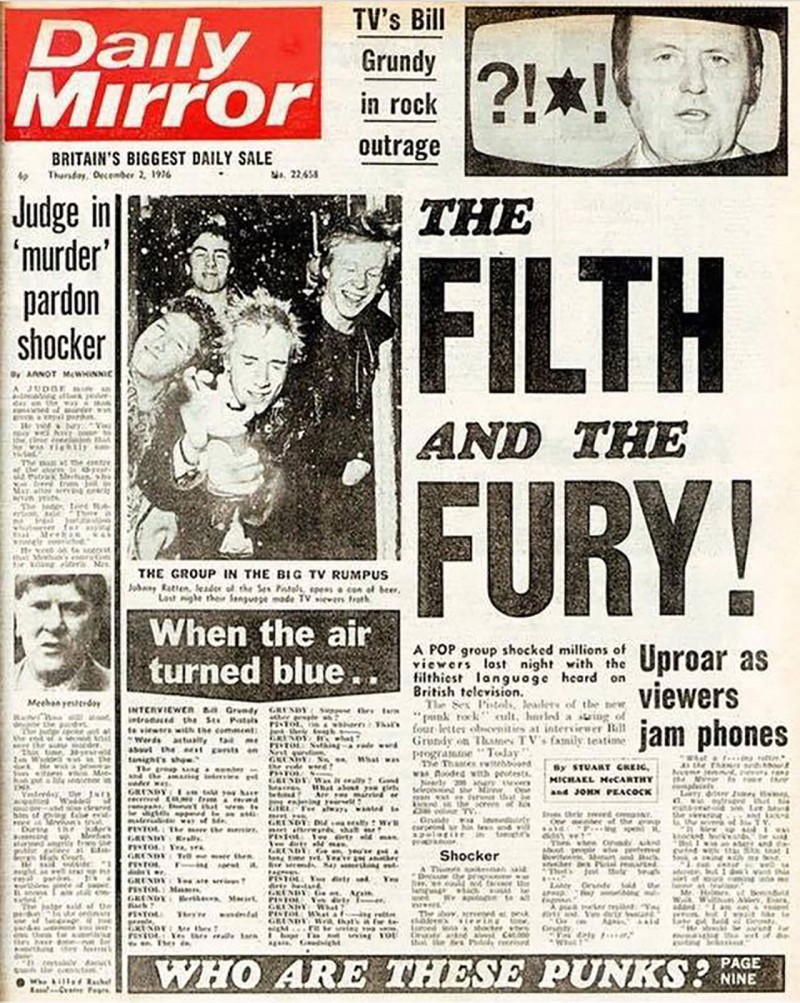

Though the U.S. does its damndest to keep up these days, no one in 1976 could match the outrage machinery of the UK press. As rock photographer and manager Leee Black Childers put it in the oral history of punk, Please Kill Me, the tabloids “can work the populace into a frenzy.” McLaren goes on record to say, “I knew the Bill Grundy show was going to create a huge scandal. I genuinely believed it would be history in the making.” We might expect him to take credit after the fact, but in any case, it worked: the day after the band’s appearance on the Grundy-hosted Today show on Thames Television, every tabloid paper featured them on the front page. The Daily Mirror provided the title of Julien Temple’s 2000 documentary with their clever headline, “The Filth and the Fury.”

Even in 2008, a survey showed the Grundy interview as the most requested clip in UK television history. With all this hype, you might be disappointed if you’re one of the few who hasn’t seen it. Though f‑bombs on TV can still cause a minor stir, a few mumbled curse words will hardly garner the kind of publicity they did forty years ago. McLaren claims punk rock began that day on the Today show, and that’s true, at least, for the viewing public who would have been treated to an appearance from Queen if Freddie Mercury hadn’t developed a crippling toothache. Instead, they were introduced to Paul Cook in a Vivienne Westwood naked breasts t‑shirt, and Glen Matlock, Steve Jones, and Johnny Rotten tossing insults at Grundy, who egged them on, hit on the teenage Siouxsie Sioux, part of the band’s entourage, and may have been drunk, though he denied it.

It may be one of the least witty exchanges in television history, and that’s saying a lot. But for all the pearl-clutching over the band’s crudity, it’s maybe Grundy who comes off looking the worse. More interesting than the interview itself is the hyperbolic fallout, as well as what happened immediately afterward. The station was flooded with complaints, and for some reason, its telephone system rerouted unanswered calls to the green room, where the band and their followers had decamped. “A producer on the programme ignored instructions to remain in the room,” notes Jon Bennett at Team Rock. “The result? The group started answering the phones and dishing out even more abuse. How this evaded the press at the time remains a mystery.” Indeed. It’s doubtful McLaren could have planned it, but the image evokes the sneer of every punk who has ever spit on the pious insistence that TV spoonfeed its viewers middle-class decorum with their advertising, sports, wish-fulfilling fantasies, and infotainment.

Related Content:

Watch the Sex Pistols’ Very Last Concert (San Francisco, 1978)

The Sex Pistols’ 1976 Manchester “Gig That Changed the World,” and the Day the Punk Era Began

The Sex Pistols Play in Dallas’ Longhorn Ballroom; Next Show Is Merle Haggard (1978)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness