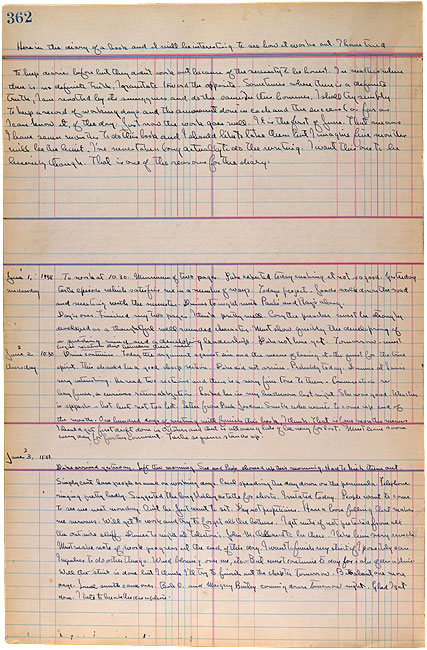

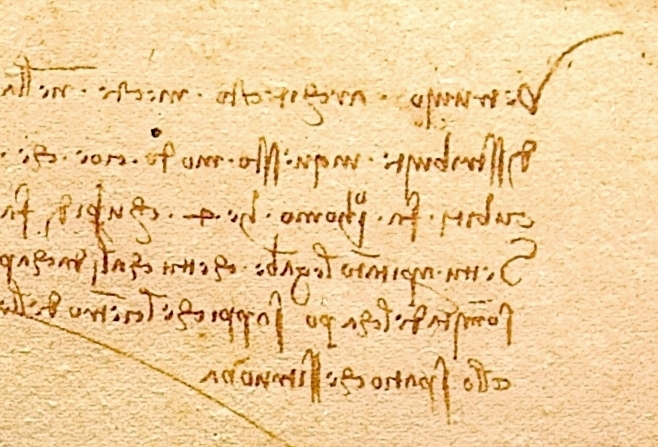

As the standout example of the “Renaissance Man” ideal, Leonardo da Vinci racked up no small number of accomplishments in his life. He also had his eccentricities, and tried his hand at a number of experiments that might look a bit odd even to his admirers today. In the case of one practice he eventually mastered and with which he stuck, he tried his hand in a more literal sense than usual: Leonardo, the evidence clearly shows, had a habit of writing backwards, starting at the right side of the page and moving to the left.

“Only when he was writing something intended for other people did he write in the normal direction,” says the Museum of Science. Why did he write backwards? That remains one of the host of so far unanswerable questions about Leonardo’s remarkable life, but “one idea is that it may have kept his hands clean. People who were contemporaries of Leonardo left records that they saw him write and paint left handed. He also made sketches showing his own left hand at work. As a lefty, this mirrored writing style would have prevented him from smudging his ink as he wrote.”

Or Leonardo could have developed his “mirror writing” out of fear, a hypothesis acknowledged even by books for young readers: “Throughout his life, he was worried about the possibility of others stealing his ideas,” writes Rachel A. Koestler-Grack in Leonardo Da Vinci: Artist, Inventor, and Renaissance Man. “The observations in his notebooks were written in such a way that they could be read only by holding the books up to a mirror.” The blog Walker’s Chapters makes a representative counterargument: “Do you really think that a man as clever as Leonardo thought it was a good way to prevent people from reading his notes? This man, this genius, if he truly wanted to make his notes readable only to himself, he would’ve invented an entirely new language for this purpose. We’re talking about a dude who conceptualized parachutes even before helicopters were a thing.”

Perhaps the most widely seen piece of Leonardo’s mirror writing is his notes on Vitruvian Man (a piece of which appears at the top of the post), his enormously famous drawing that fits the proportions of the human body into the geometry of both a circle and a square (and whose elegant mathematics we featured last week). Many examples of mirror writing exist after Leonardo, from his countryman Matteo Zaccolini’s 17th-century treatise on color to the 18th- and 19th-century calligraphy of the Ottoman Empire to the front of ambulances today. Each of those has its function, but one wonders whether as curious a mind as Leonardo’s would want to write backwards simply for the joy of mastering and using a skill, any skill, however much it might baffle others — or indeed, because it might baffle them.

If you’re interested in all things da Vinci, make sure you check out the new bestselling biography, Leonardo da Vinci, by Walter Isaacson.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Bizarre Caricatures & Monster Drawings

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Leonardo da Vinci’s Handwritten Resume (1482)

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To Do List (Circa 1490) Is Much Cooler Than Yours

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.