FYI: If you sign up for a MasterClass course by clicking on the affiliate links in this post, Open Culture will receive a small fee that helps support our operation.

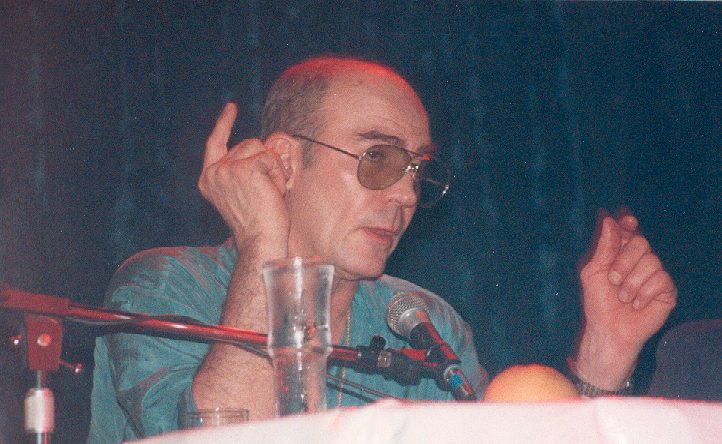

The one about the dog whisperer, the one about how job interviews and sports drafts work (or don’t), the one about the ideas Apple took from Xerox PARC to create the personal computer as we know it: most of us have a favorite Malcolm Gladwell article. (I happen to like the one on how an Austrian architect invented the American shopping mall, so much that I’ve previously cited it here on Open Culture.) Those all ran in the New Yorker, where Gladwell has contributed since 1996. Since then, his enterprises have expanded to include bestselling books, much-circulated TED Talks, and even a hit podcast. How does he do it?

We now have the chance to learn just that in a new online course taught by Gladwell himself, going live this spring on Masterclass. Though many know him only from his speaking or audiovisual media, the core of his work still gets done when he puts words on a page. Hence the title and subject matter of his Masterclass: “Malcolm Gladwell Teaches Writing.”

If you sign up for MasterClass through an All-Access Pass, we’re promised insight into how Gladwell uses ordinary subjects to help “millions of readers devour complex ideas like behavioral economics and performance prediction” and an understanding of how he “researches topics, crafts characters, and distills big ideas into simple, powerful narratives.”

“We’re going to talk about suspense, structure, research, humility, characters, puzzles, and semicolons,” says Gladwell in the course’s trailer above. He also mentions one of the common mistakes he’ll correct: that “writers spend a lot of time thinking about how to start their stories and not a lot of time thinking about how to end them.” If you’ve always wanted to write Gladwellian prose — “at an eighth grade level,” as he himself describes it, “but with ideas that are super sophisticated” — this Masterclass’ twenty lessons will get you putting in a few of the ten thousand (or so) hours you need to attain mastery. That might sound like a lot of time, but keep Gladwell’s words of guidance in mind: “The job of the writer is not to supply the ideas; it is to be patient enough to find the ideas.”

You can take this class by signing up for a MasterClass’ All Access Pass. The All Access Pass will give you instant access to this course and 85 others for a 12-month period.

Related Content:

Malcolm Gladwell: Taxes Were High and Life Was Just Fine

Malcolm Gladwell: What We Can Learn from Spaghetti Sauce

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.