Image via Wikimedia Commons

The word quixotic derives, of course, from Miguel Cervantes’ irreverent early 17th century satire, Don Quixote. From the novel’s eponymous character it carries connotations of antiquated, extravagant chivalry. But in modern usage, quixotic usually means “foolishly impractical, marked by rash lofty romantic ideas.” Such designations apply in the case of Jorge Luis Borges’ story, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” in which the titular academic writes his own Quixote by recreating Cervantes’ novel word-for-word.

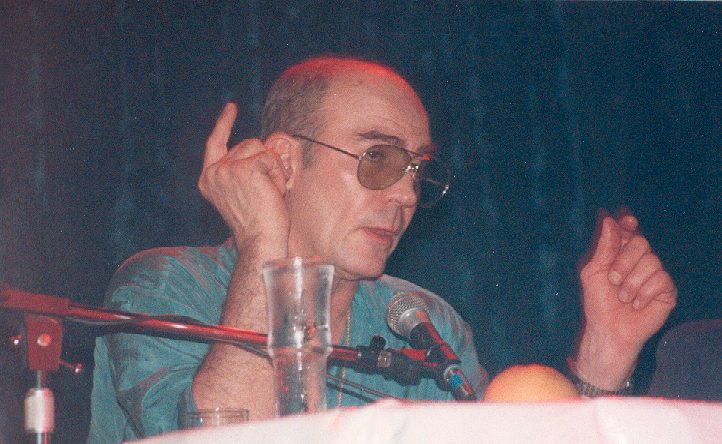

Why does this fictional minor critic do such a thing? Borges’ explanations are as circuitously mysterious as you might expect. But we can get a much more straightforward answer from a modern-day Quixote—an individual who has undertaken many a “foolishly impractical” quest: Hunter S. Thompson. Though he would never be mistaken for a knight-errant, Thompson did tilt at more than a few windmills, including Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, from which he typed whole pages, word-for-word “just to get the feeling,” writes Louis Menand at The New Yorker, “of what it was like to write that way.”

“You know Hunter typed The Great Gatsby,” an awestruck Johnny Depp told The Guardian in 2011, after he’d played Thompson himself in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and a fictionalized version of him in an adaptation of Thompson’s lost novel The Rum Diaries. “He’d look at each page Fitzgerald wrote, and he copied it. The entire book. And more than once. Because he wanted to know what it felt like to write a masterpiece.” This exercise prepared him to write one, or his cracked version of one, 1972’s gonzo account of a more-than-quixotic road trip, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Menand points out that Thompson first called the book The Death of the American Dream, likely inspired by Fitzgerald’s first Gatsby title, The Death of the Red White and Blue.

Thompson referred to Gatsby frequently in books and letters. Just as often, he referenced another literary hero—and pugnacious Fitzgerald competitor—Ernest Hemingway. He first began typing out Gatsby while employed at Time magazine as a copy boy in 1958, one of many magazine and newspaper jobs in a “pattern of disruptive employment,” writes biographer Kevin T. McEneaney. “Thompson appropriated armloads of office supplies” for the task, and also typed out Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and “some of Faulkner’s stories—an unusual method for learning prose rhythm.” He was fired the following year, not for misappropriation, but for “his unpardonable, insulting wit at a Christmas party.”

In a 1958 letter to his hometown girlfriend Ann Frick, Thompson named the Fitzgerald and Hemingway novels as two especially influential books, along with Brave New World, William Whyte’s The Organization Man, and Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything (or “Girls before Girls”), a novel that “hardly belongs in the abovementioned company,” he wrote, and which he did not, presumably, copy out on his typewriter at work. Surely, however, many a Thompson close reader has discerned the traces of Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and Hemingway in his work, particularly the latter, whose macho escapades and epic drinking bouts surely inspired more than just Thompson’s writing.

In Borges’ “Pierre Menard,” the title character first sets out to “be Miguel de Cervantes”—to “Learn Spanish, return to Catholicism, fight against the Moor or Turk, forget the history of Europe from 1602 to 1918….” He finds the undertaking not only “impossible from the outset,” but also “the least interesting” way to go about writing his own Quixote. Thompson may have discovered the same as he worked his way through his influences. He could not become his heroes. He would have to take what he’d learned from inhabiting their prose, and use it as fuel for his literary firebombs–or, seen differently, for his idealistic, impractical, yet strangely noble (in their way) knight’s quests.

Not since Thompson’s Nixonian heyday has there been such need for a ferocious outlaw voice like his. He may have become a stock character by the end of his life, caricatured as Uncle Duke in Doonesbury, given pop culture sainthood by Depp’s unhinged portrayal. But “at its best,” writes Menand, “Thompson’s anger, in writing, was a beautiful thing, fearless and funny and, after all, not wrong about the shabbiness and hypocrisy of American officialdom.” Perhaps even now, some hungry young intern is typing out Fear and Loathing word-for-word, preparing to absorb it into his or her own 21st century repertoire of barbed-wire truth-telling about “the death of the American dream.” The method, it seems, may work with any great writer, be it Cervantes, Fitzgerald, or Hunter S. Thompson.

Related Content:

Read 18 Lost Stories From Hunter S. Thompson’s Forgotten Stint As a Foreign Correspondent

Hunter S. Thompson, Existentialist Life Coach, Gives Tips for Finding Meaning in Life

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness