So you want to be a rock and roll star? Or a writer, or a filmmaker, or a comedian, or what-have-you…. And yet, you don’t know where to start. You’ve heard you need to find your own voice, but it’s difficult to know what that is when you’re just beginning. You have too little experience to know what works for you and what doesn’t. So? “Steal,” as the great John Cleese advises above, “or borrow or, as the artists would say, ‘be influenced by’ anything that you think is really good and really funny and appeals to you. If you study that and try to reproduce it in some way, then it’ll have your own stamp on it. But you have a chance of getting off the ground with something like that.”

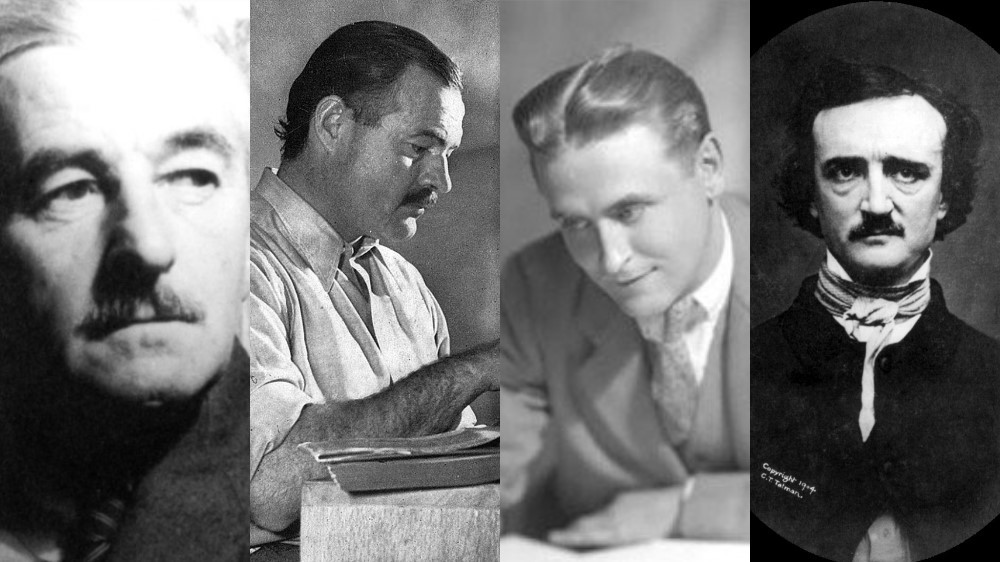

Cleese goes on to sensibly explain why it’s nearly impossible to start with something completely new and original; it’s like “trying to fly a plane without any lessons.” We all learn the rudiments of everything we know by imitating others at first, so this advice to the budding writer and artist shouldn’t sound too radical. But if you need more validation for it, consider William Faulkner’s exhortation to take whatever you need from other writers. The beginning writer, Faulkner told a class at the University of Virginia, “takes whatever he needs, wherever he needs, and he does that openly and honestly.” There’s no shame in it, unless you fail to ever make it your own. Or, says Faulkner, to make something so good that others will steal from you.

One theory of how this works in literature comes from critic Harold Bloom, who argued in The Anxiety of Influence that every major poet more or less stole from previous major poets; yet they so misread or misinterpreted their influences that they couldn’t help but produce original work. T.S. Eliot advanced a more conservative version of the claim in his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” We have a “tendency to insist,” wrote Eliot, on “those aspects or parts of [a poet’s] work in which he least resembles anyone else.” (Both Eliot and Faulkner used the masculine as a universal pronoun; whatever their biases, no gender exclusion is implied here.) On the contrary, “if we approach a poet without this prejudice we shall often find that not only the best, but the most individual parts of his work may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously.”

It may have been a requirement for Eliot that his literary predecessors be long deceased, but John Cleese suggests no such thing. In fact, he worked closely with many of his favorite comedy writers. The point he makes is that one should “copy someone who’s really good” in order to “get off the ground.” In time—whether through becoming better than your influences, or misreading them, or combining their parts into a new whole—you will, Cleese and many other wise writers suggest, develop your own style.

Cleese has liberally discussed his influences, in his recent autobiography and elsewhere, and one can clearly see in his work the impression comedic forbears like Laurel and Hardy and the writer/actors of The Goon Show had on him. But whatever he stole or borrowed from those comedians he also made entirely his own through practice and perseverance. Just above, see a television special on Cleese’s comedy heroes, with interviews from Cleese, legends who followed him, like Rik Mayall and Steve Martin, and those who worked side-by-side with him on Monty Python and other classic shows.

Related Content:

John Cleese Explores the Health Benefits of Laughter

John Cleese’s Philosophy of Creativity: Creating Oases for Childlike Play

John Cleese, Ringo Starr and Peter Sellers Trash Priceless Art (1969)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness