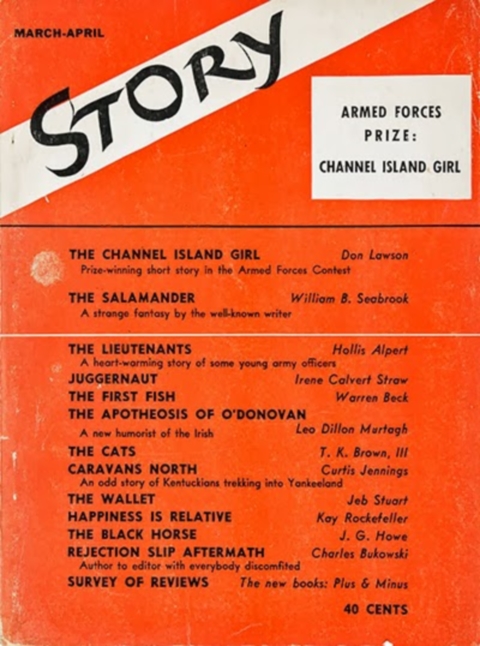

“Everyone’s got to start somewhere,” a banal platitude that expresses a truism worth repeating: wherever you are, you’ve got to get started. If you’re John Updike (who would have been 82 years old yesterday), you start where so many other accomplished figures have, the Harvard Lampoon. If you’re Charles Bukowski… believe it or not, you actually start in an equally renowned publication. Bukowski’s first fiction appeared in Story, a magazine that helped launch the careers of Cheever, Salinger, Saroyan, Carson McCullers and Richard Wright.

But if you’re Charles Bukowski, you come out swinging. Your first published work in 1944 is a nonsense story written as an eff you to the editor, Whit Burnett. You feature Mr. Burnett as a character, along with a cat who shakes hands (sort of), a prostitute named Millie, a few card-playing drunks, an imperious “short story instructress,” and a mysterious “bleary-eyed tramp.” Oh, and you open the story by quoting verbatim one of Burnett’s rejection letters:

Dear Mr. Bukowski:

Again, this is a conglomeration of extremely good stuff and other stuff so full of idolized prostitutes, morning-after vomiting scenes, misanthropy, praise for suicide etc. that it is not quite for a magazine of any circulation at all. This is, however, pretty much the saga of a certain type of person and in it I think you’ve done an honest job. Possibly we will print you sometime but I don’t know exactly when. That depends on you.

Sincerely yours,

Whit Burnett

I won’t spoil it for you—you must read (or listen to below) “Aftermath of a Lengthy Rejection Slip” for yourself—but the letter sets up a typically Bukowskian punchline: wry and sarcastic and wistful and lyrical all at once.

Bukowski was 24 and had only been writing for two years by this time. He later recalled being very unhappy with the publication. For one, writes Booktryst, “it had been buried in the End Pages section of the magazine as, Bukowski felt, a curiosity rather than a serious piece of writing.” However, Bukowski had already sent Story dozens of what he considered serious pieces of writing before penning “Aftermath,” which he admits he tamed for the sake of Burnett’s sensibilities. In an interview near the end of his life, Bukowski remembered submitting to the magazine “a couple of short stories a week for maybe a year and half. The story they finally accepted was mild in comparison to the others. I mean in terms of content and style and gamble and exploration and all that.”

Bukowski may have been bitter, but his first publication, and last submission to Story, might deserve credit for inspiring a lifetime of boozy material: looking back, he recalls that after the perceived slight, he “drank and became one of the best drinkers anywhere, which takes some talent also.” Everybody’s got to start somewhere.

Booktryst has more to the story, as well as several images of the rare 1944 Bukowski issue of Story. Above, in two parts, listen to the story in the wonderfully dry baritone of Tom O’Bedlam, whom you may already know from our previous posts on Bukowski’s poems “Nirvana” and “So You Want to Be a Writer?”

Related Content:

Three Interpretations of Charles Bukowski’s Melancholy Poem “Nirvana”

Listen to Charles Bukowski Poems Being Read by Bukowski Himself & the Great Tom Waits

So You Want to Be a Writer?: Charles Bukowski Explains the Dos & Don’ts

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness