Which best describes your museum-going experience? Inspiration and spiritual refreshment? Or a soul crushing attempt to fight your way past the hoards there for the latest blockbuster exhibit, with a too-heavy bag and a whining, foot sore companion in tow?

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to lose yourself in contemplation of a single work? What about that giant one at the top of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Grand Staircase? For every visitor who pauses to take it in, another thousand stream by with hardly a glance.

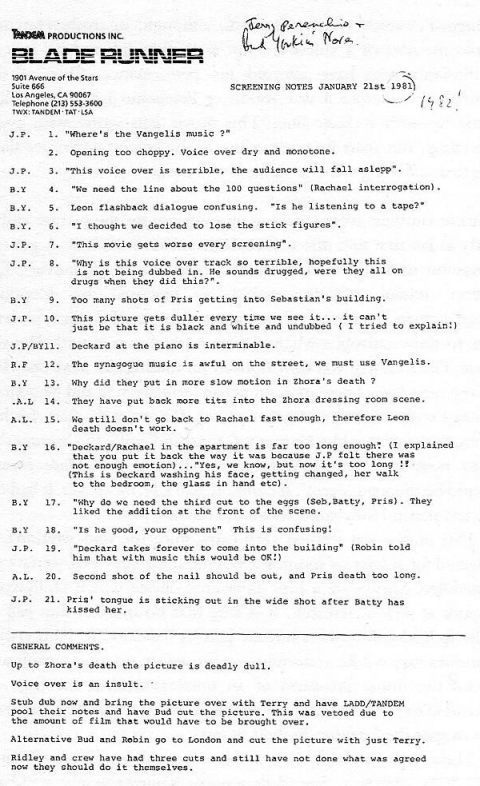

The above commentary by curator of Italian paintings, Xavier Salomon, may well turn Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s The Triumph of Marius into one of the Met’s hottest attractions. It’s often difficult for the average museum-goer to understand what the deal is in one of these densely populated, 19th century oils. Salomon supplies the needed historical context—general Gaius Marius parading captive Numidian king Jugurtha through the streets upon his triumphal return to Rome.

Things get even more interesting when he translates the Latin inscription at the top of the canvas: “The Roman people behold Jugurtha laden with chains.” In other words, you can forgo the hero worship of the title and concentrate on the bad guy. This, Salomon speculates, is what the artist had in mind when swathing Jugurtha in that eye-catching red cape. Jugurtha may be the loser, but his refusal to be humbled before the crowd is winsome.

As is 82nd and 5th, an online series that aims to celebrate 100 transformative works of art from the museum’s collection before year’s end. In addition to Salomon’s compelling thoughts on The Triumph of Marius, some pleasures thus far include Melanie Holcomb, Associate Curator of Medieval Art and The Cloisters, geeking out over illustrated manuscript pages and fashion and costume curator Andrew Bolton recalling his first encounter with one of designer Alexander McQueen’s most extreme garments. Each video is supplemented with a tab for further exploration. You can also find the talks collected on YouTube.

Brilliantly conceived and executed, these commentaries provide virtual museum-goers with a highly personal tour, and can only but enrich the experience of anyone lucky enough to visit in the flesh.

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of Free Art Catalogs from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Google Art Project Expands, Bringing 30,000 Works of Art from 151 Museums to the Web

Free: The Guggenheim Puts 65 Modern Art Books Online

Ayun Halliday has her fingers crossed for some commentary on the Met’s hunky Standing Hanuman.