When Joni Mitchell heard the great cabaret artist Mabel Mercer in concert, she was so struck by the older woman’s rendition of “Both Sides Now,” the enduring ballad Mitchell wrote at the tender age of 23, that she went backstage to show her appreciation:

… but I didn’t tell her that I was the author. So, I said, y’know, I’ve heard various recordings of that song, but you bring something to it, y’know, that other people haven’t been able to do. You know, it’s not a song for an ingenue. You have to bring some age to it.

Well, she took offense. I insulted her. I called her an old lady, as far as she was concerned. So I got out of there in a hell of a hurry!

But I think I finally became an old lady myself and could sing the song right.

This is just one of many candid treats to be found in Mitchell’s interview with Elton John, for his Apple Music 1 show Rocket Hour.

For the most part, Mitchell’s reminiscences coalesce around various iconic tracks from her nearly sixty years in the music industry.

“Carey,” off Mitchell’s 1971 album Blue, sparks memories of an exploding stove during a hippie-era sojourn in Matala on Crete’s south coast, with an Odyssey reference thrown in for good measure.

“Amelia” was hatched, as were most of the tunes on 1976’s Hejira, while Mitchell was on a solo road trip in a secondhand Mercedes, an experience that caused her to dwell on the first female aviator to cross the Atlantic solo. (She scribbled down lyrics that had come to her at the wheel whenever she pulled over for lunch.)

Regarding “Sex Kills” from 1994’s Turbulent Indigo, John quotes a Rolling Stone article in which Mitchell discussed the “ugliness” she was detecting in popular music:

I think it’s on the increase. Especially towards women. I’ve never been a feminist, but we haven’t had pop songs up until recently that were so aggressively dangerous to women.

“What did you mean by that?” John asks. “ People saying rap music with ‘my hos’ and stuff like that?”

“Oh, well, y’know, yeah,” Mitchell says, “Hos and booty, y’know, hahahah.”

She may not seem overly fussed about it now, but don’t get her started on what young women wear to the Grammys!

John also invited Mitchell to discuss three songs that have influenced her.

Her picks:

Lambert, Hendricks & Ross’s “Charleston Alley” (a musical epiphany as a high schooler at a college party)

Edith Piaf’s “Les Trois Cloches” (a musical epiphany as an 8‑year-old at a birthday party)

And Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” (dancing ‘round the jukebox at Saskatoon swimming pool)

Circling back to “Both Sides Now,” Mitchell prefers the orchestral arrangement she recorded as an alto in 2002 to the original’s girlish soprano, with its possibly unearned perspective. (“It’s not a song for an ingenue…”)

When I performed it, the orchestra gathered around me and I’ve played with classical musicians before and they were always reading the Wall Street Journal behind their sheet music and they always treat you like it’s a condescension to be playing with you, but everybody, the men — Englishmen! — were weeping!

Perhaps you too will be moved to tears, as singer-songwriter Brandi Carlile was during a performance of “Both Sides Now” as part of the 2022 Newport Folk Festival’s Joni Jam, Mitchell’s first show in 22 years, owing to a period of major disillusionment with the music business as well as a 2015 brain aneurysm.

Tune into more episodes of Elton John’s Rocket Hour here.

Related Content

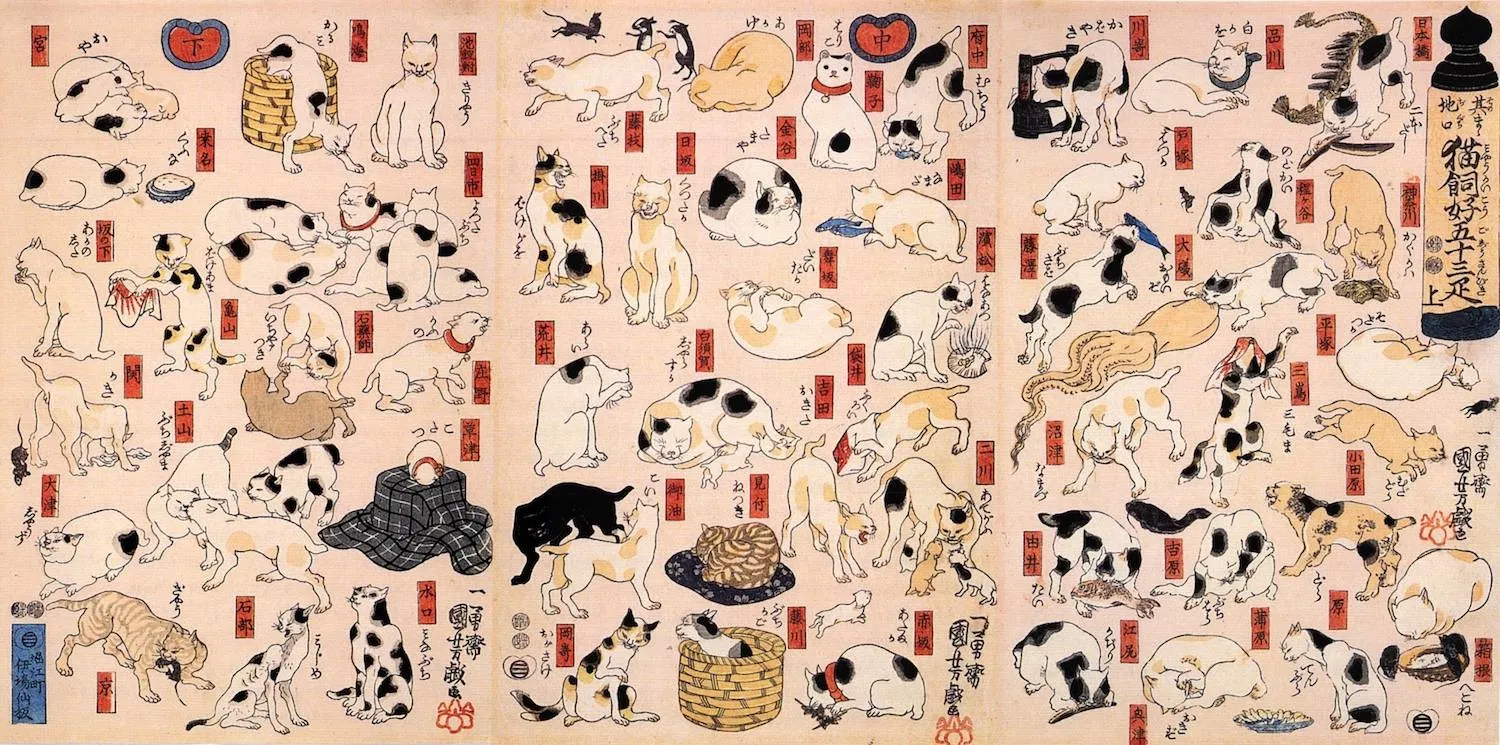

Songs by Joni Mitchell Re-Imagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers & Vintage Movie Posters

Hear Demos & Outtakes of Joni Mitchell’s Blue on the 50th Anniversary of the Classic Album

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and the soon to be released Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.