“Just listen. Silence is the poetics of space. What it means to be in a place…. Silence isn’t the absence of something, but the presence of everything.” – acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton

The study of acoustic ecology doesn’t get much mainstream attention. But if you’ve been a reader of Open Culture, you’ve likely come across a post about preserving natural sounds by streaming recordings of the world’s many environments. These projects all, in one way or another, contribute to goals articulated by Canadian composer and writer R. Murray Schafer, the “self-declared father” of acoustic ecology, which involves the study, conservation, and appreciation of environmental sound.

As Neil Clarke notes at Earth.fm, Schaffer’s complex discipline can seem difficult to grasp, as it “straddles ‘acoustics, architecture, linguistics, music, psychology, sociology and urban planning.’ ” Maybe all we need to know to appreciate the goals of Earth.fm — another excellent entry in a growing list of natural-sound streaming sites – comes through in Clarke’s description of Schaffer’s World Soundscape Project (WSP):

It was hoped that, eventually, the WSP would be able to create a balance “between the human community and its sonic environment.” To this end, listening and “ear-cleaning” practices, including “soundwalks” – a walking meditation where a high sonic awareness is maintained – were designed to increase individuals’ consciousness of the sounds around them. By prompting engagement with the realities of contemporary soundscapes, listeners were intended to gain awareness of their part in these soundscapes’ creation, and therefore appreciate their responsibility towards them.

Schaffer began recording soundscapes (a word he coined) in Vancouver in the early 70s. Since then, his work has inspired and complemented that of other field recordists/acoustic theorists/sound archivists like Bernie Krauss and Gordon Hempton. Although the early acoustic ecologists could not have foreseen streaming media, it has without a doubt become for many of us a dominant vehicle for sound in our daily lives, including sounds of the natural world.

Without an appreciation for the sounds of natural silence (which we know, since John Cage, does not mean absolute quiet), our understanding of rainforests, deserts, and oceans as living, breathing realities can become dulled, just as much as we lose touch with the green spaces outside our windows. Reconnecting through sound has the dual effect of calming our inner states and attuning us more closely to the outer world as it is, without the distractions of recorded music and video laid overtop.

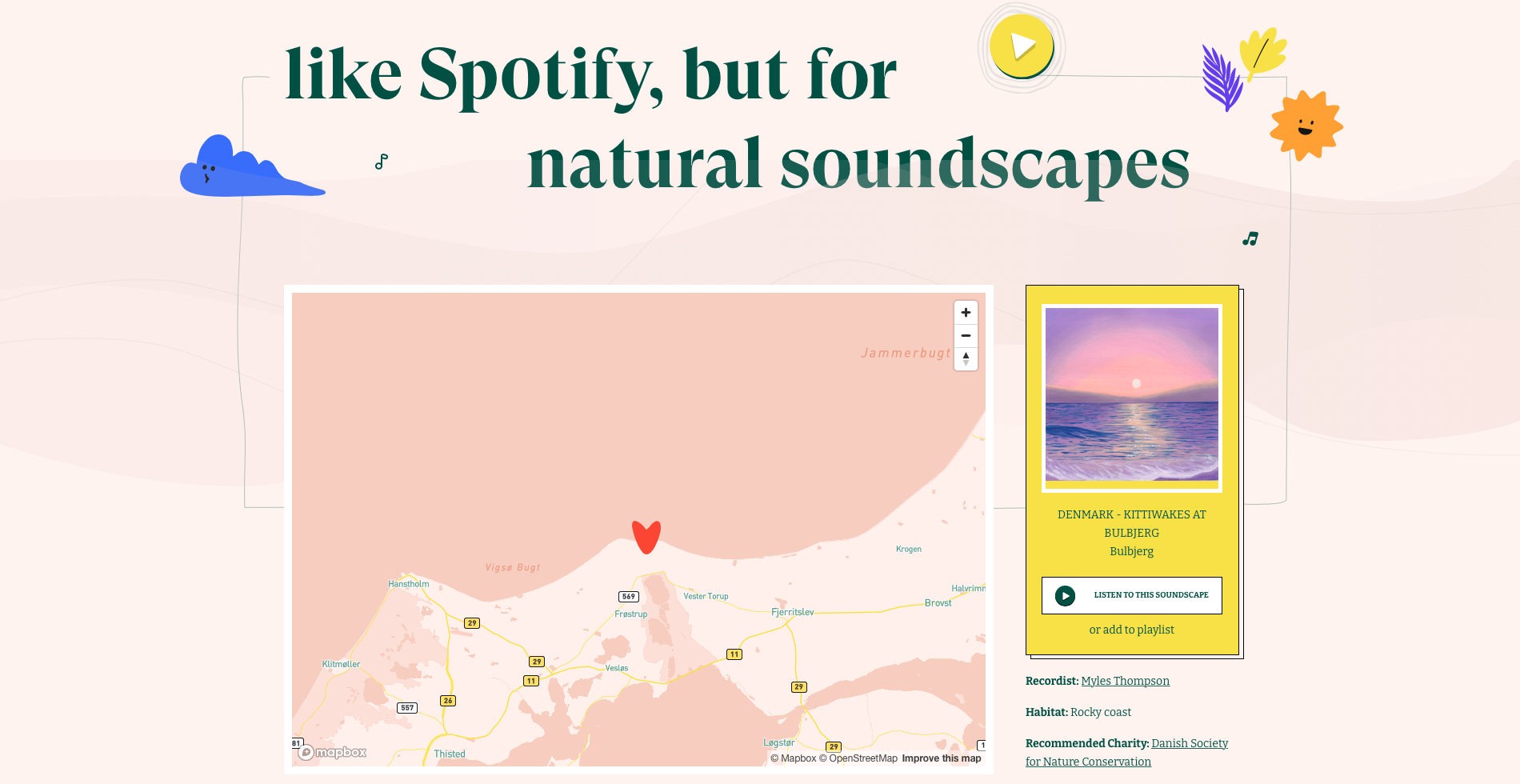

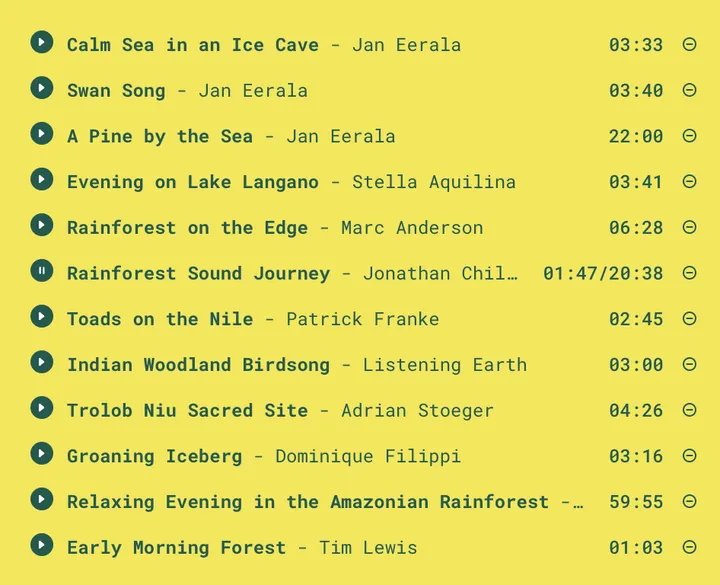

Billing itself as “like Spotify, but for natural soundscapes,” Earth.fm, offers not a rival streaming service, but an alternative in which users can make their own playlists, The Verge explains, “zipping from Brazil to Egypt in a matter of minutes.” New sounds are added every three days. “You can listen to bird species in Malaysia or India or forest sounds in Ghana. The sounds are gathered from numerous contributors who have experience recording the natural world in places including Brazil, Spain, Norway, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.”

We can intuit Earth.fm’s mission not only as therapeutic and preservationist but also as an ethical attempt to approach the crisis streaming media has introduced in the arts. Human-made sounds (or “anthropophy”) are just as much a part of our environment as those made by frogs, rivers, and antelope. Our constant, often mindless streaming, however — made possible by infinite digital repositories and cheap (for now) energy — can be seen as a form of noise pollution, and a significant contributor to energy overconsumption.

The ethics of streaming must account for the impact on the beings (in this case, us) who make these sounds. Big Tech commodification of music requires a “vast conversation,” argues an essay on the Earth.fm site, that includes “the format’s impact on those at the heart of this whole undertaking: those who create music.” By implication, Earth.fm and other sites that stream acoustic recordings of natural sounds (like those in the links below), offer an ethical alternative to music streaming — one that reconnects us, Elizabeth Waddington writes on the site, to “the music of a changing world.” Learn more about Earth.fm’s activities here.

Related Content:

Free: Download the Sublime Sights & Sounds of Yellowstone National Park

Sounds of the Forest: A Free Audio Archive Gathers the Sounds of Forests from All Over the World

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness