Do a search on the word “polymath” and you will see an image or reference to Leonardo da Vinci in nearly every result. Many historical figures—not all of them world famous, not all Europeans, men, or from the Italian Renaissance—fit the description. But few such recorded individuals were as feverishly active, restlessly inventive, and astonishingly prolific as Leonardo, who left riddles enough for scholars to solve for many lifetimes.

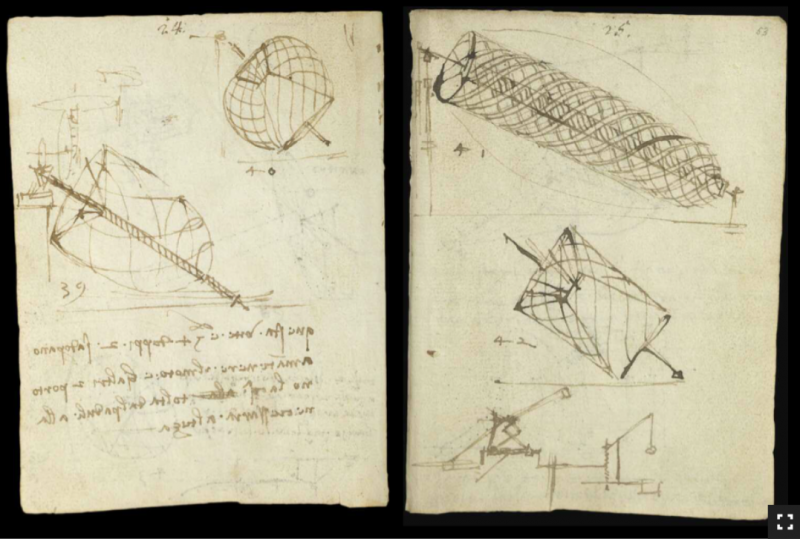

Leonardo himself, though world-renowned for his talents in the fine arts, spent more of his time conceiving scientific studies and engineering projects. “When he wrote in the early 1480s to Ludovico Sforza, then ruler of Milan, to offer him his services,” remarks Catherine Yvard, Special Collections curator at the Victoria and Albert National Art Library, “he advertised himself as a military engineer, only briefly mentioning his artistic skills at the end of the list.”

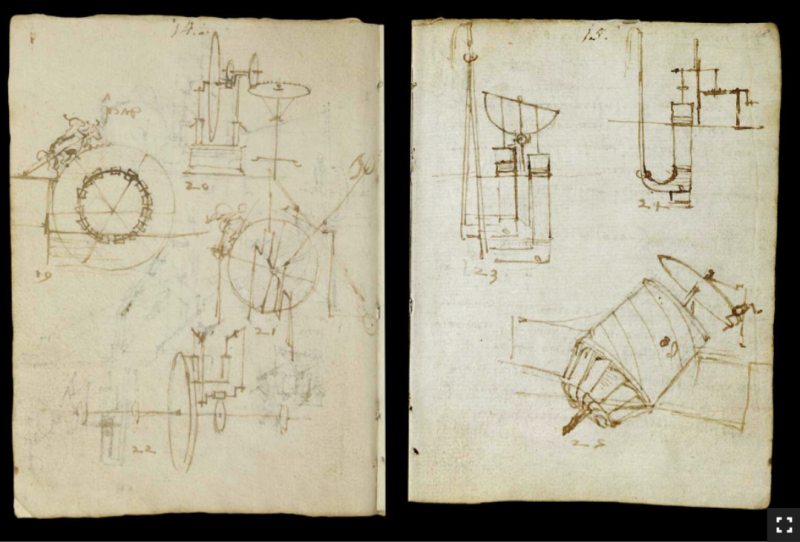

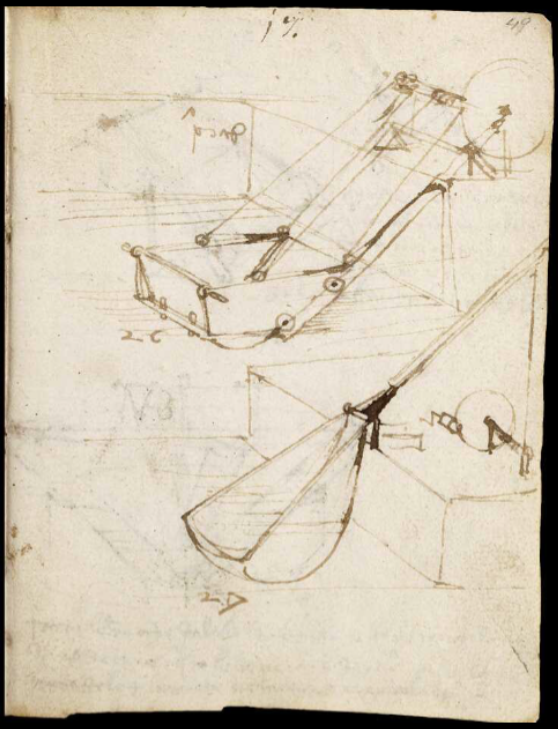

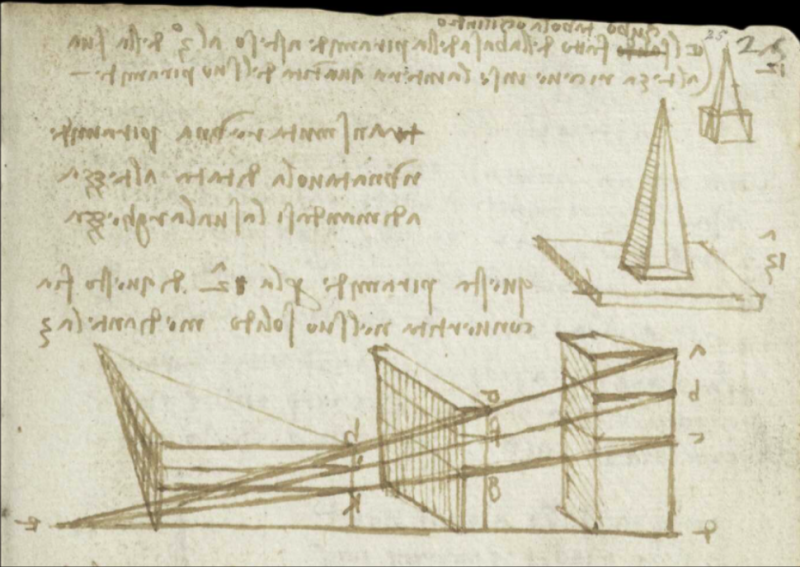

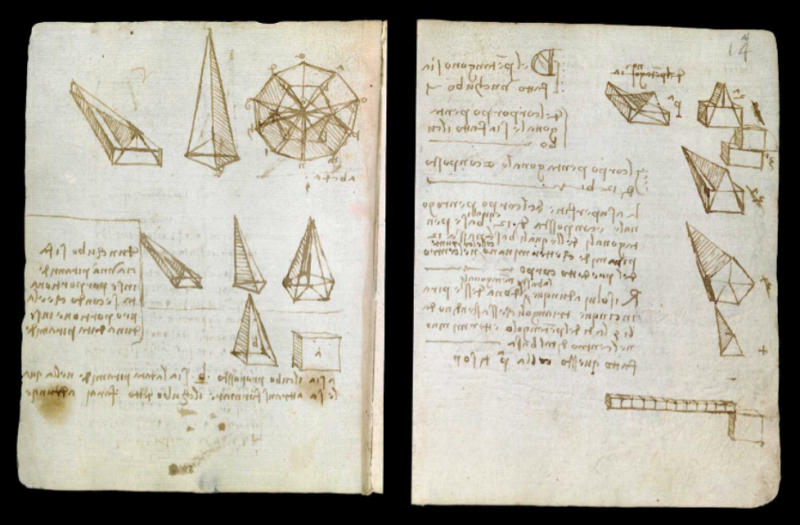

But since so few of his projects were, or could be, realized in his lifetime, we can only experience them through his mostly inaccessible, and generally indecipherable, notebooks, which he began keeping after the Duke accepted his application. “None of Leonardo’s predecessors, contemporaries or successors used paper quite like he did,” notes the Victoria and Albert Museum site, “a single sheet contains an unpredictable pattern of ideas and inventions—the workings of both a designer and a scientist.”

Part of the difficulty of piecing his legacy together stems from the fact that his hundreds of pages of notes have been distributed across several institutions and private collections, not all of them accessible to researchers. But ambitious digitization projects are erasing those barriers. We recently featured one, a joint effort of the British Library and Microsoft that brought 570 pages from the Codex Arundel collection to the web. As The Art Newspaper reports, the Victoria and Albert has now launched a similar endeavor, digitizing the Codex Forster notebooks, so named because they came from the private collection of John Forster in 1876.

This collection includes some of Leonardo’s earliest notebooks. Codex Forster I, now online, contains the earliest notebook the V&A holds, dating from about 1487, and the latest, from 1505. “Written in Leonardo’s famous ‘mirror-writing,’” the V&A notes, “the subjects explored within range from hydraulic engineering to a treatise on measuring solids.” Forster II and III should come online soon. “We are planning to make these two other volumes also fully accessible online in 2019 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death,” says Yvard.

The most innovative aspect of this particular project is the use of IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework), a technology that “has enabled us to present the codex in a new way,” remarks Kati Price, V&A’s head of digital media. “We’ve used deep-zoom functionality… to present some of the most spectacular and detailed items in our collection.” Scholars and laypeople alike can take a very close-up look at the many schematics and technical diagrams in the notebooks and see Leonardo’s mind and hand at work.

But while all of us can marvel at the sight of his engineering genius, when it comes to reading his handwriting, we’ll have to rely on experts. Let’s hope the museum will someday supply translations for nonspecialists. In the meantime, explore the digitized manuscripts here.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To Do List (Circa 1490) Is Much Cooler Than Yours

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness