Over the course of this tumultuous year, new CIA director Mike Pompeo has repeatedly indicated that he would move the Agency in a “more aggressive direction.” In response, at least one person took on the guise of former Chilean president Salvador Allende and joked, incredulously, “more aggressive”? In 1973, the reactionary forces of General Augusto Pinochet overthrew Allende, the first elected Marxist leader in Latin America. Pinochet then proceeded to institute a brutal 17-year dictatorship characterized by mass torture, imprisonment, and execution. The Agency may not have orchestrated the coup directly but it did at least support it materially and ideologically under the orders of President Richard Nixon, on a day known to many, post-2001, as “the other 9/11.”

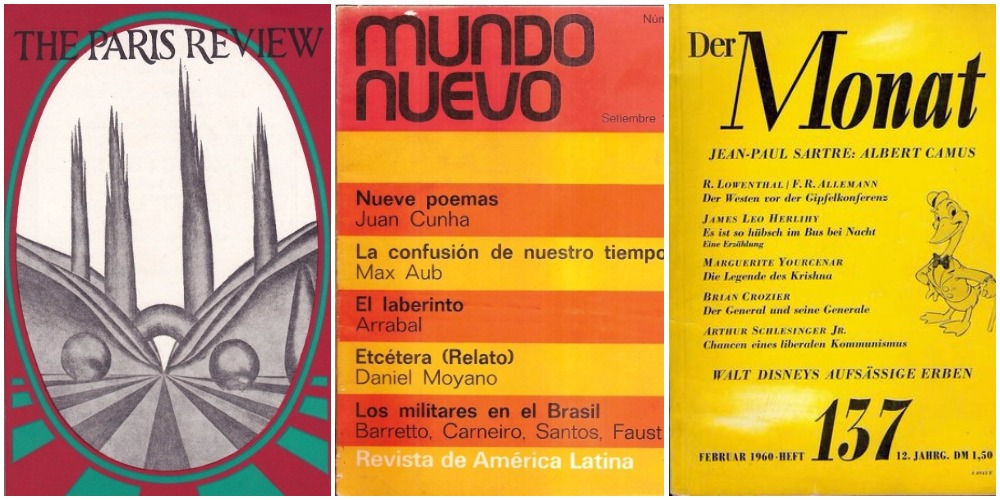

The Chilean coup is one of many CIA interventions into the affairs of Latin America and the former European colonies in Africa and Asia after World War II. It is by now well known that the Agency “occasionally undermined democracies for the sake of fighting communism,” as Mary von Aue writes at Vice, throughout the Cold War years. But years before some of its most aggressive initiatives, the CIA “developed several guises to throw money at young, burgeoning writers, creating a cultural propaganda strategy with literary outposts around the world, from Lebanon to Uganda, India to Latin America.” The Agency didn’t invent the post-war literary movements that first spread through the pages of magazines like The Partisan Review and The Paris Review in the 1950s. But it funded, organized, and curated them, with the full knowledge of editors like Paris Review co-founder Peter Matthiessen, himself a CIA agent.

The Agency waged a cold culture war against international Communism using many of the people who might seem most sympathetic to it. Revealed in 1967 by former agent Tom Braden in the pages of the Saturday Evening Post, the strategy involved secretly diverting funds to what the Agency called “civil society” groups. The focal point of the strategy was the CCF, or “Congress for Cultural Freedom,” which recruited liberal and leftist writers and editors, oftentimes unwittingly, to “guarantee that anti-Communist ideas were not voiced only by reactionary speakers,” writes Patrick Iber at The Awl. As Braden contended in his exposé, in “much of Europe in the 1950s, socialists, people who called themselves ‘left’—the very people whom many Americans thought no better than Communists—were about the only people who gave a damn about fighting Communism.”

No doubt some literary scholars would find this claim tendentious, but it became agency doctrine not only because the CIA saw funding and promoting writers like James Baldwin, Gabriel Garcia Márquez, Richard Wright, and Ernest Hemingway as a convenient means to an end, but also because many of the program’s founders were themselves literary scholars. The CIA began as a World War II spy agency called the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). After the war, says Guernica magazine editor Joel Whitney in an interview with Bomb, “some of the OSS guys became professors at Ivy League Universities,” where they recruited people like Matthiessen.

The more liberal guys who were part of the brain trust that formed the CIA saw that the Soviets in Berlin were getting masses of people from other sectors to come over for their symphonies and films. They saw that culture itself was becoming a weapon, and they wanted a kind of Ministry of Culture too. They felt the only way they could get this paid for was through the CIA’s black budget.

McCarthy-ism reigned at the time, and “the less sophisticated reactionaries,” says Whitney, “who represented small states, small towns, and so on, were very suspicious of culture, of the avant-garde, the little intellectual magazines, and of intellectuals themselves.” But Ivy League agents who fancied themselves tastemakers saw things very differently.

Whitney’s book, Finks: How the CIA Tricked the World’s Best Writers, documents the Agency’s whirlwind of activity behind literary magazines like the London-based Encounter, French Preuves, Italian Tempo Presente, Austrian Forum, Australian Quadrant, Japanese Jiyu, and Latin American Cuadernos and Mundo Nuevo. Many of the CCF’s founders and participants conceived of the enterprise as “an altruistic funding of culture,” Whitney tells von Aue. “But it was actually a control of journalism, a control of the fourth estate. It was a control of how intellectuals thought about the US.”

While we often look at post-war literature as a bastion of anti-colonial, anti-establishment sentiment, the pose, we learn from researchers like Iber and Whitney, was often carefully cultivated by a number of intermediaries. Does this mean we can no longer enjoy this literature as the artistic creation of singular geniuses? “You want to know the truth about the writers and publications you love,” says Whitney, “but that shouldn’t mean they’re ruined.” Indeed, the Agency’s cultural operations went far beyond the little magazines. The Congress of Cultural Freedoms used jazz musicians like Louie Armstrong, Dave Brubeck, and Dizzy Gillespie as “goodwill ambassadors” in concerts all over the world, and funded exhibitions of Abstract Expressionists like Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollack, and Willem de Kooning.

The motives behind funding and promoting modern art might mystify us unless we include the context in which such cultural warfare developed. After the Cuban Revolution and subsequent Communist fervor in former European colonies, the Agency found that “soft liners,” as Whitney puts it, had more anti-Communist reach than “hard liners.” Additionally, Communist propagandists could easily point to the U.S.‘s socio-political backwardness and lack of freedom under Jim Crow. So the CIA co-opted anti-racist writers at home, and could silence artists abroad, as it did in the mid-60s when Louis Armstrong went behind the Iron Curtain and refused to criticize the South, despite his previous strong civil rights statements. The post-war world saw thriving free presses and arts and literary cultures filled with bold experimentalism and philosophical and political debate. Knowing who really controlled these conversations offers us an entirely new way to view the directions they inevitably seemed to take.

Related Content:

How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

Louis Armstrong Plays Historic Cold War Concerts in East Berlin & Budapest (1965)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness