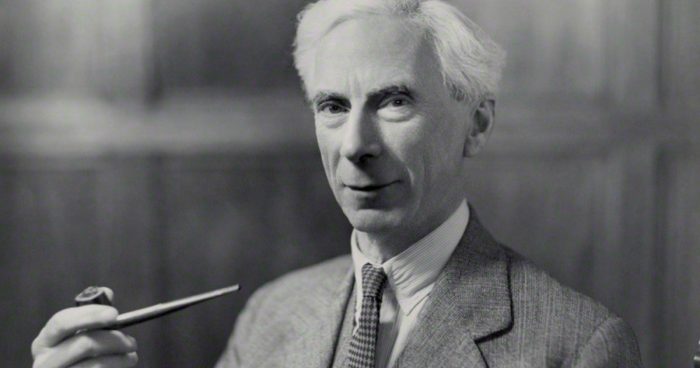

Image by Daniele Prati, via Flickr Commons

Many writers recoil at the notion of discussing where they get their ideas, but Kurt Vonnegut spoke on the subject willingly. “I get my ideas from dreams,” he announced early in one speech, adding, “the wildest dream I have had so far is about The New Yorker magazine.” In this dream, “the magazine has published a three-part essay by Jonathan Schell which proves that life on Earth is about to end. I am supposed to go to the largest Gothic cathedral in the world, where all the people are waiting, and say something wonderful — right before a hydrogen bomb is dropped on the Empire State Building.”

It stands to reason that a such a vivid, frightening, and somehow funny scenario would unfold in the unconscious mind of a man who wrote such vivid, frightening, and somehow funny novels. (Vonnegut’s own interpretation? “I consider myself an important writer, and I think The New Yorker should be ashamed that it has never published me.”) As it happens, he did deliver these words in a cathedral, namely New York City’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine in the spring of 1982.

This was just months after Schell’s three-part essay “The Fate of the Earth” (all three parts of it still available online) really ran in The New Yorker, and Cold War fears about the probability of a hydrogen bomb really dropping on America ran high. Vonnegut’s speech was one of a series of Sunday sermons the Cathedral had lined up on the subject of nuclear disarmament, assembling the rest of the roster from military, scientific, and activist fields. The author of Cat’s Cradle, Slaughterhouse-Five, and Breakfast of Champions—fresh off a trip to the Galapagos Islands with the St. John the Divine’s Bishop Paul Moore—presumably represented the realm of letters.

“At the time, NYPR Archives Director Andy Lanset covered the Vonnegut sermon as a volunteer for the WNYC News Department,” wrote WNYC’s William Rodney Allen in 2014 on the rediscovery and posting of Lanset’s recording. (The same public radio station, incidentally, would fifteen or so years later commission Vonnegut for a series of reports from the afterlife.) Now we can not only read but also hear Vonnegut, in his own voice, trying to imagine aloud a series of “fates worse than death.” Why? Not simply to indulge his famous sense of gallows humor, but in order to put the nuclear threat, and the anxieties it generated, into the proper context.

“I am sure you are sick and tired of hearing how all living things sizzle and pop inside a radioactive fireball,” Vonnegut says, going on to assure his audience that “scientists, for all their creativity, will never discover a method for making people deader than dead. So if some of you are worried about being hydrogen-bombed, you are merely fearing death. There is nothing new in that. If there weren’t any hydrogen bombs, death would still be after you.”

In any event, despite having shuffled through several candidates (“Life without petroleum?”), Vonnegut can come up with no fate believably worse than death besides crucifixion. But given that non-crucified human beings nearly always and everywhere prefer life to death, perhaps “we might pray to be rescued from our inventiveness” which gave us the ability to destroy all life on Earth. But “the inventiveness which we so regret now may also be giving us, along with the rockets and warheads, the means to achieve what has hitherto been an impossibility, the unity of mankind.”

Vonnegut sees this promise mainly in television, whose terribly realistic sounds and images ensure that “the people of every industrialized nation are nauseated by war by the time they are ten years old.” A veteran of the Second World War, he himself remembers a very different time, back when “it used to be necessary for a young soldier to get into fighting before he became disillusioned about war,” back when “it was unusual for an American, or a person of any nationality, for that matter, to know much about foreigners.”

Even before the 1980s, “thanks to modern communications, we have seen sights and heard sounds from virtually every square mile of the land mass on this planet,” and so “know for certain that there are no potential human enemies anywhere who are anything but human beings almost exactly like ourselves. They need food. How amazing. They love their children. How amazing. They obey their leaders. How amazing. They think like their neighbors. How amazing.”

Modern communications have, of course, come astonishingly far in the 35 years since Vonnegut’s Sunday sermon, but our fears about nuclear annihilation have had a way of resurfacing. In recent months, the American people have even heard talk of a reinvigorated nuclear arms race from their new president, a man whose rise detractors partly blame on modern communication technology — not a lack of it, but an excess.

“The global village that was once the internet has been replaced by digital islands of isolation that are drifting further apart each day,” writes Mostafa M. El-Bermawy in a Wired piece on the threat social-media “filter bubbles” pose to democracy. “We need to remind ourselves that there are humans on the other side of the screen who want to be heard and can think and feel like us while at the same time reaching different conclusions.” Recent developments would probably disappoint Vonnegut (not that they would surprise him), but he’d surely get a kick, as he always did, out of the irony of it all.

Related Content:

Kurt Vonnegut: Where Do I Get My Ideas From? My Disgust with Civilization

In 1988, Kurt Vonnegut Writes a Letter to People Living in 2088, Giving 7 Pieces of Advice

22-Year-Old P.O.W. Kurt Vonnegut Writes Home from World War II: “I’ll Be Damned If It Was Worth It”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.