“We can say of Shakespeare,” wrote T.S. Eliot—in what may sound like the most backhanded of compliments from one writer to another—“that never has a man turned so little knowledge to such great account.” Eliot, it’s true, was not overawed by the Shakespearean canon; he pronounced Hamlet “most certainly an artistic failure,” though he did love Coriolanus. Whatever we make of his ambivalent, contrarian opinions of the most famous author in the English language, we can credit Eliot for keen observation: Shakespeare’s universe, which can seem so sprawlingly vast, is actually surprisingly spare given the kinds of things it mostly contains.

This is due in large part to the visual limitations of the stage, but perhaps it also points toward an author who made great works of art from humble materials. Look, for example, at a search cloud of the Bard’s plays.

You’ll find one the front page of the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive, created by Michael John Goodman, an independent researcher, writer, educator, curator and image-maker. The cloud on the left features a galaxy composed mainly of elemental and archetypal beings: “Animals,” “Castles and Palaces,” “Crowns,” “Flora and Fauna,” “Swords,” “Spears,” “Trees,” “Water,” “Woods,” “Death.” One thinks of the Zodiac or Tarot.

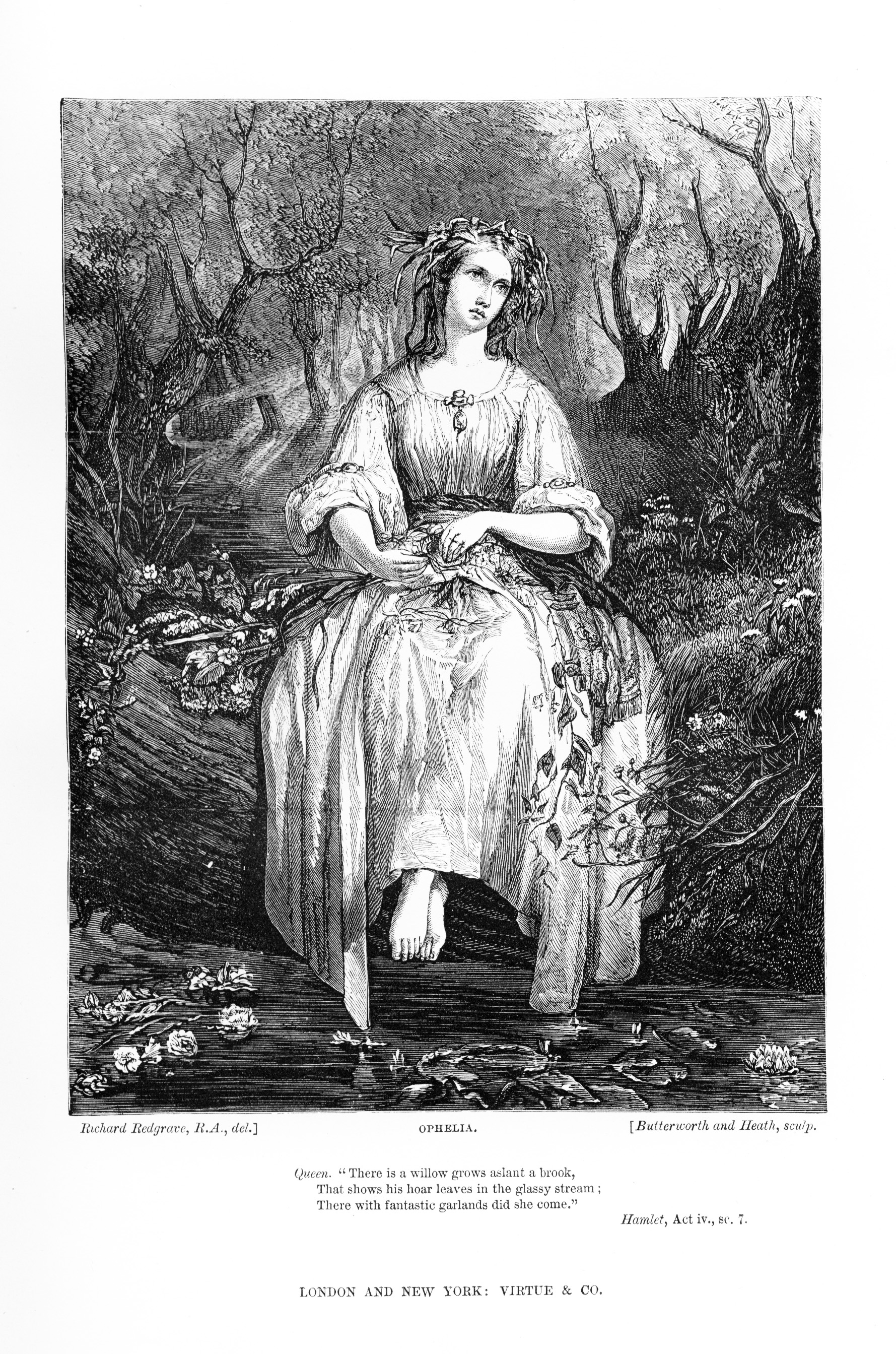

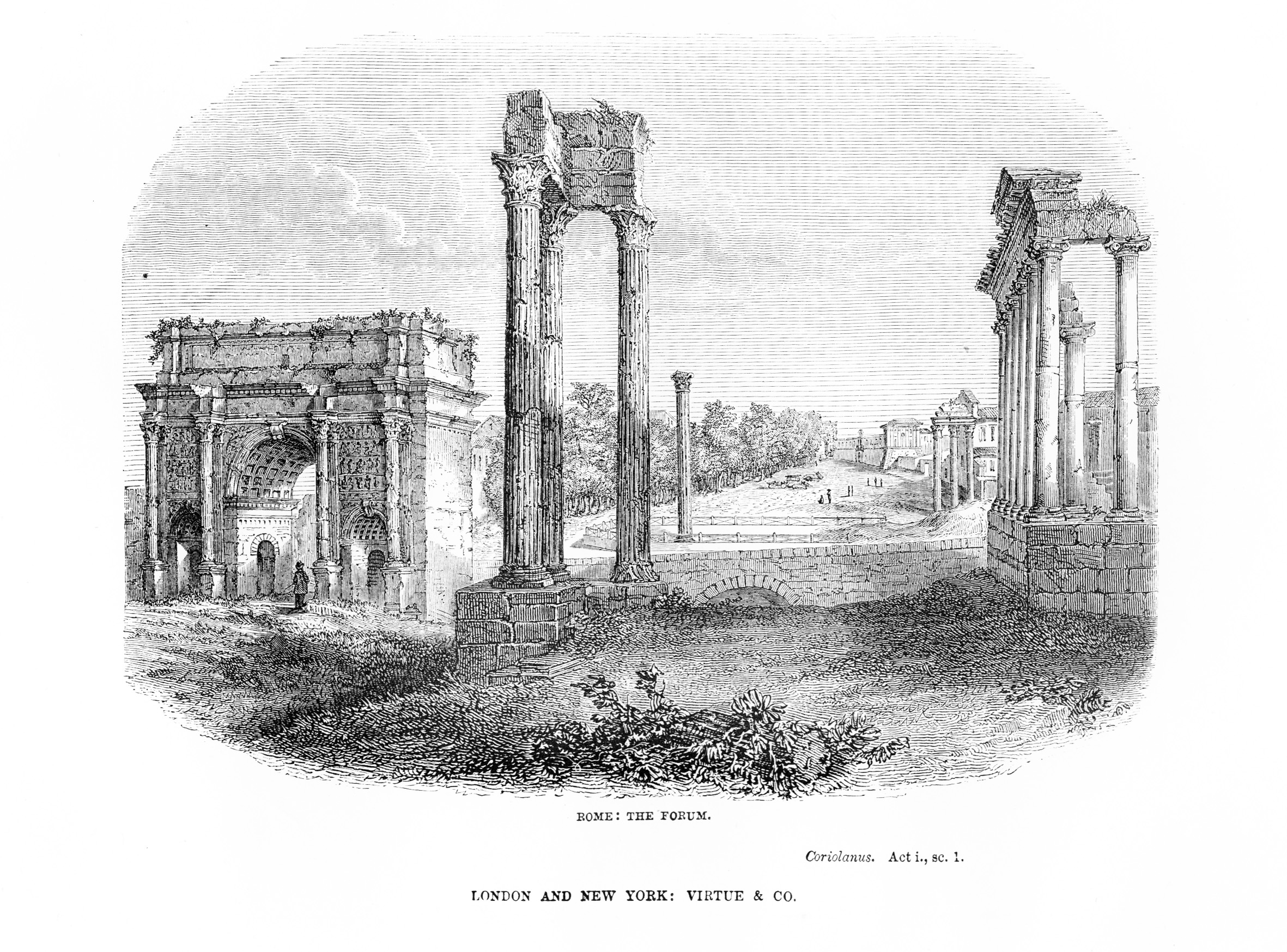

This particular search cloud, however, does not represent the most prominent terms in the text, but rather the most prominent images in four collections of illustrated Shakespeare plays from the Victorian period. Goodman’s site hosts over 3000 of these illustrations, taken from four major UK editions of Shakespeare’s Complete Works published in the mid-19th century. The first, published by editor Charles Knight, appeared in several volumes between 1838 and 1841, illustrated with conservative engravings by various artists. Knight’s edition introduced the trend of spelling Shakespeare’s name as “Shakspere,” as you can see in the title page to the “Comedies, Volume I,” at the top of the post. Further down, see two representative illustrations from the plays, the first of Hamlet’s Ophelia and second Coriolanus’ Roman Forum, above.

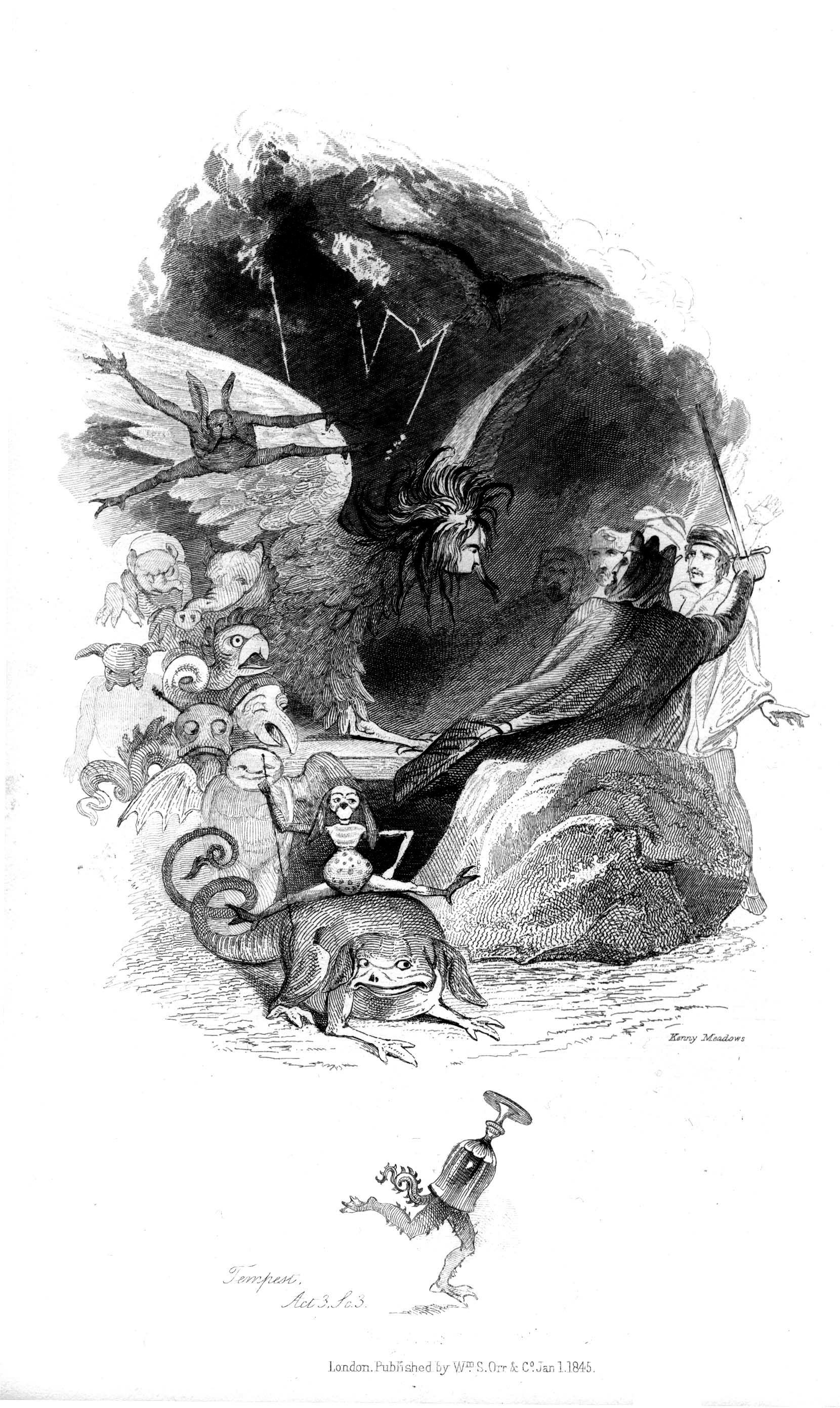

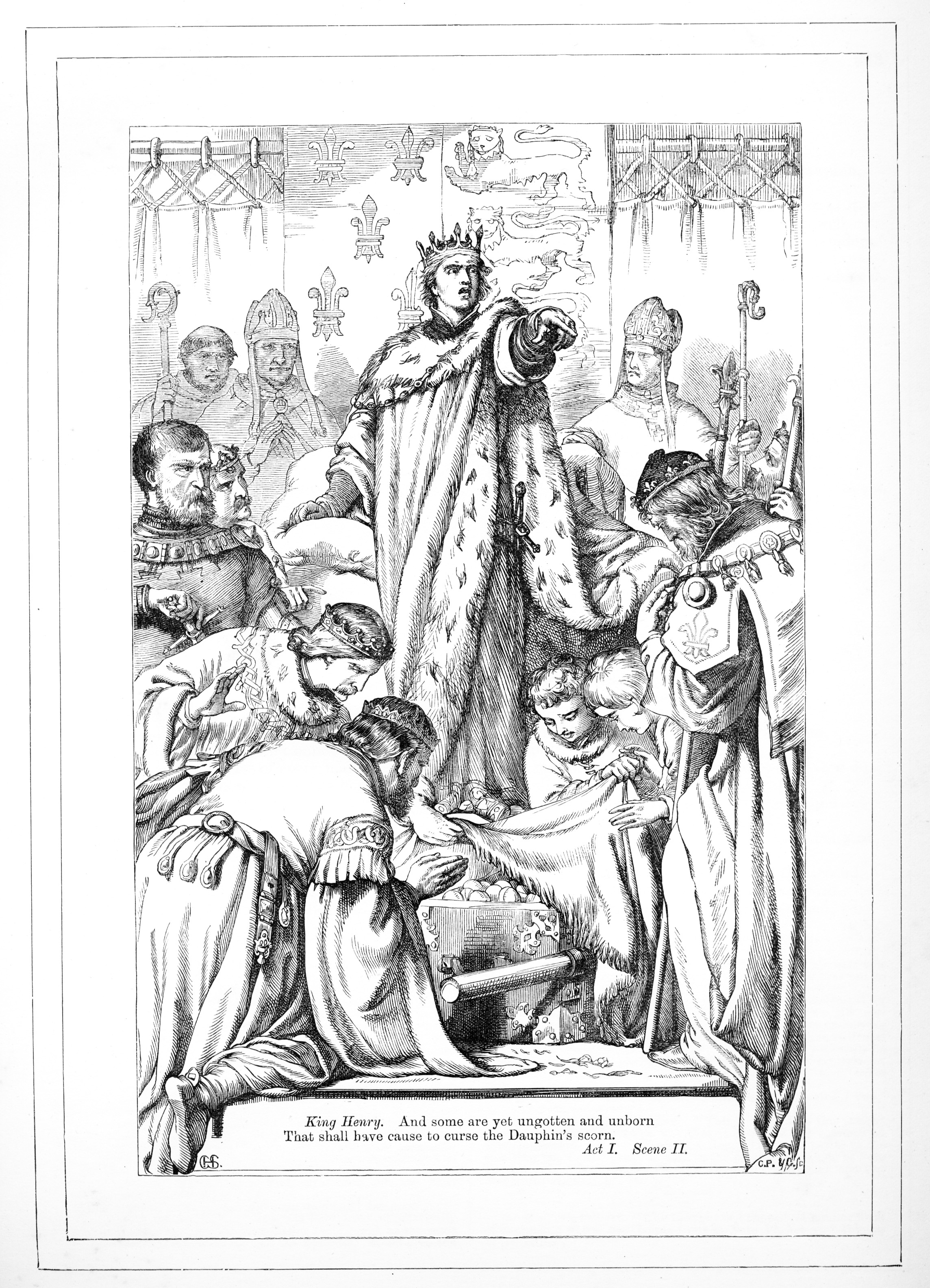

Part of a wave of “early Victorian populism” in Shakespeare publishing, Knight’s edition is joined by one from Kenny Meadows, who contributed some very different illustrations to an 1854 edition. Just above, see a Goya-like illustration from The Tempest. Later came an edition illustrated by H.C. Selous in 1864, which returned to the formal, faithful realism of the Knight edition (see a rendering of Henry V, below), and includes photograuvure plates of famed actors of the time in costume and an appendix of “Special Wood Engraved Illustrations by Various Artists.”

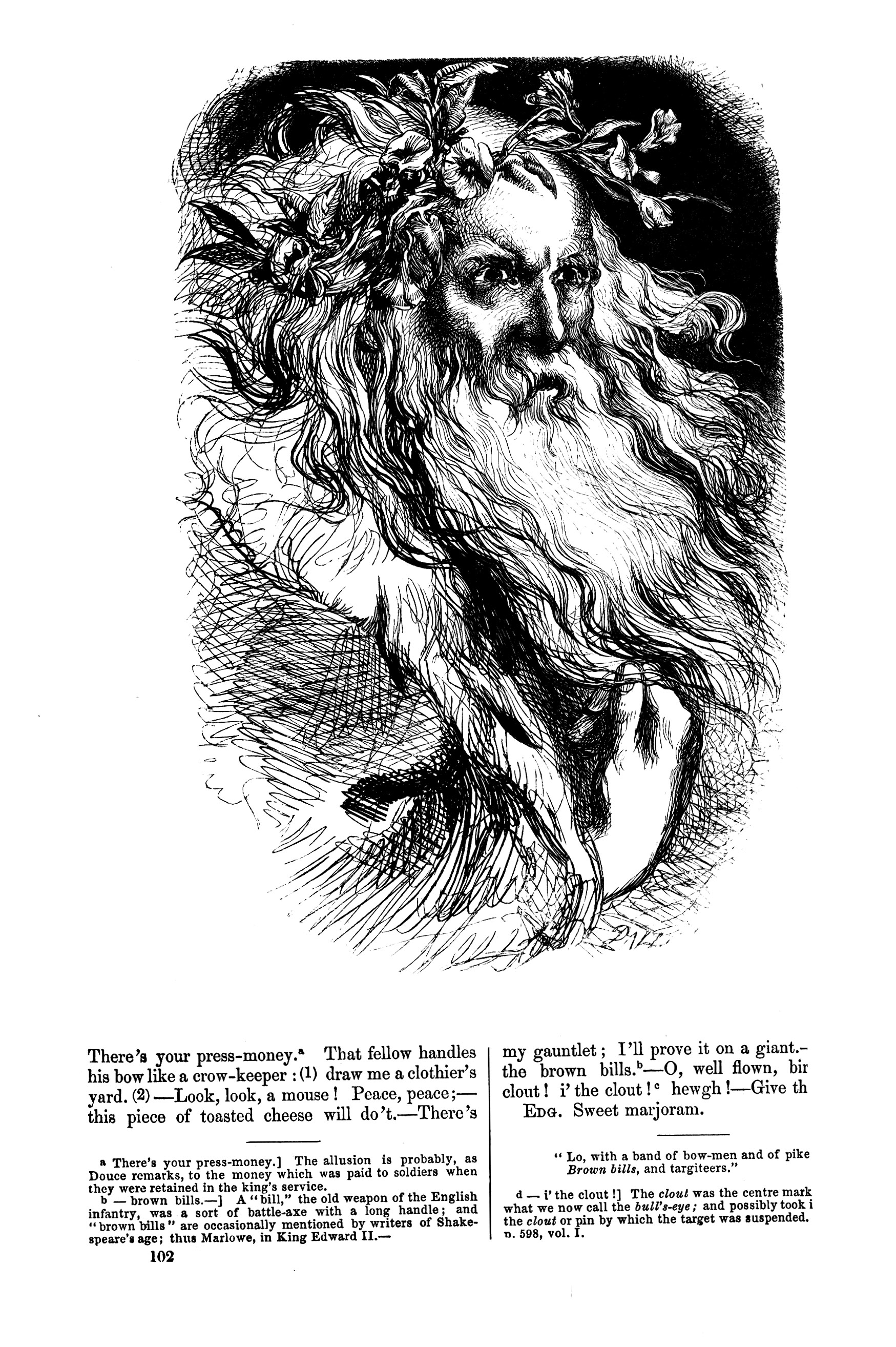

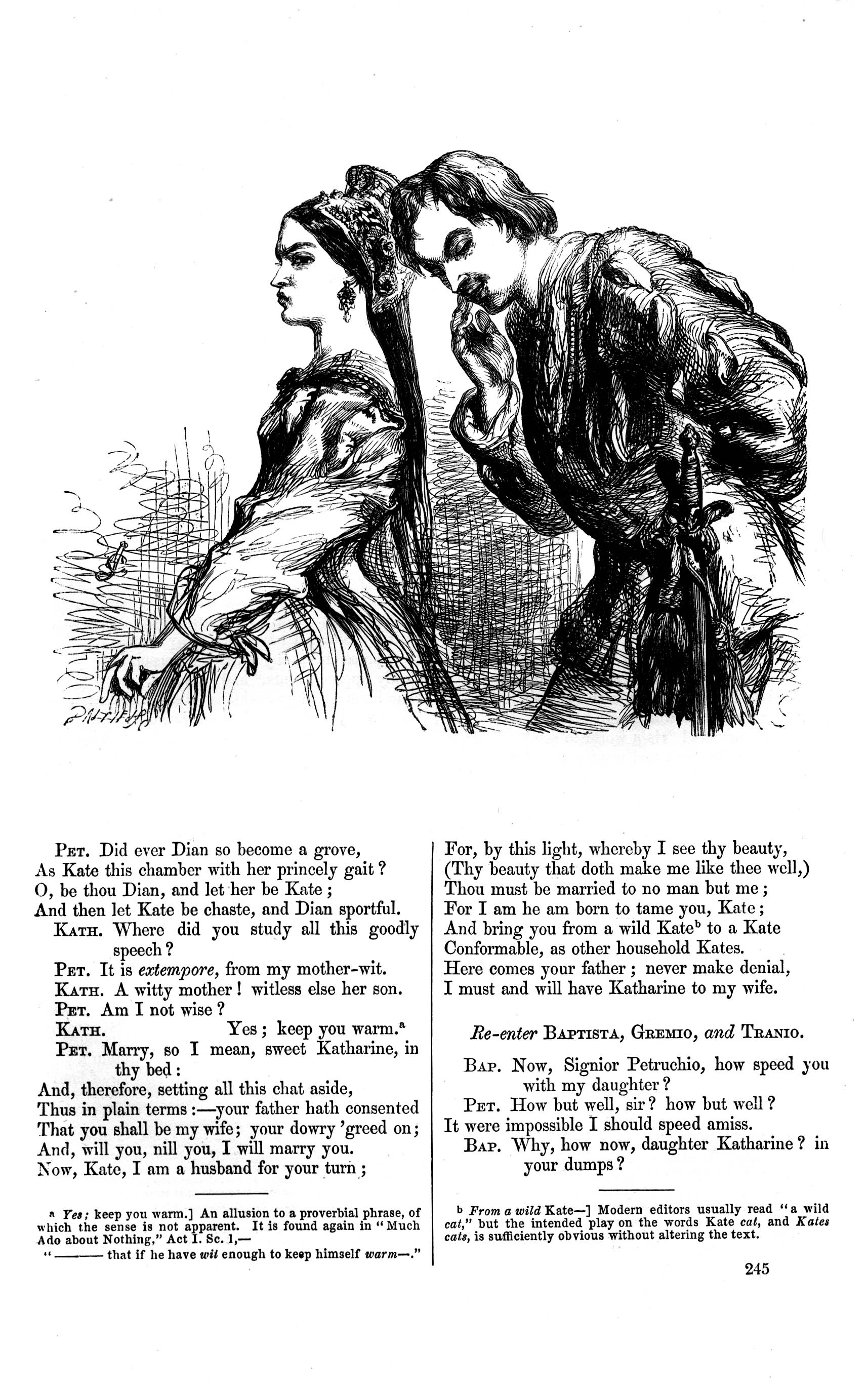

The final edition whose illustrations Goodman has digitized and catalogued on his site features engravings by artist John Gilbert. Also published in 1864, the Gilbert may be the most expressive of the four, retaining realist proportions and mise-en-scène, yet also rendering the characters with a psychological realism that is at times unsettling—as in his fierce portrait of Lear, below. Gilbert’s illustration of The Taming of the Shrew’s Katherina and Petruchio, further down, shows his skill for creating believable individuals, rather than broad archetypes. The same skill for which the playwright has so often been given credit.

But Shakespeare worked both with rich, individual character studies and broader, archetypal, material: psychological realism and mythological classicism. What I think these illustrated editions show us is that Shakespeare, whoever he (or she) may have been, did indeed have a keen sense of what Eliot called the “objective correlative,” able to communicate complex emotions through “a skillful accumulation of imagined sensory impressions” that have impressed us as much on the canvas, stage, and screen as they do on the page. The emotional expressiveness of Shakespeare’s plays comes to us not only through eloquent verse speeches, but through images of both the starkly elemental and the uniquely personal.

Spend some time with the illustrated editions on Goodman’s site, and you will develop an appreciation for how the plays communicate differently to the different artists. In addition to the search clouds, the site has a header at the top for each of the four editions. Click on the name and you will see front and back matter and title pages. In the pull-down menus, you can access each individual play’s digitized illustrations by type—“Histories,” “Comedies,” and “Tragedies.” All of the content on the site, Goodman writes, “is free through a CC license: users can share on social media, remix, research, create and just do whatever they want really!”

Update: This post originally appeared on our site in 2016. Since then, Goodman has been regularly updating the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive with more editions, giving it more richness and depth. These editions include “one published by John Tallis, which features famous actors of the time in character.” This also includes “the first ever comprehensive full-colour treatment of Shakespeare’s plays with the John Murdoch edition.” The archive, Goodman tells us, “now contains ten editions of Shakespeare’s plays and is fairly comprehensive in how people were experiencing Shakespeare, visually, in book form in the 19th Century.”

Related Content:

Take a Virtual Tour of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London

Read All of Shakespeare’s Plays Free Online, Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness