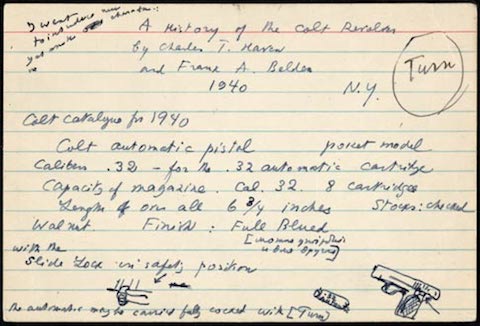

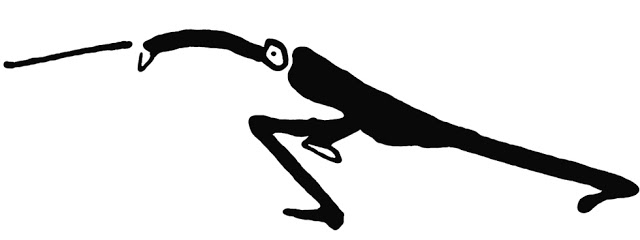

Those who know the work of Stanley Kubrick know that the longer he made films, the more insistently he demanded the best: the most flexible, varied material to adapt to his cinematic methods; the shots with the greatest impact among hundreds of takes each; the collaborators with the strongest and most useful visions, no matter their department. That very need for high craftsmanship would, you’d think, have lead the director straight to the door of Saul Bass, the graphic designer who lived and rose to eminence in his field during the same era that Kubrick lived and rose to eminence in his. They did work together on 1960’s Spartacus and 1980’s The Shining, Kubrick’s fifth and eleventh features, but as Empire’s feature on Bass’ early work explains, “it wasn’t Stanley Kubrick who recruited him to piece together Spartacus’s opening sequences.” Still, “Kubrick had been an admirer of his fellow New Yorker from his early work with Otto Preminger,” presumably including work like his still-striking titles for The Man with the Golden Arm.

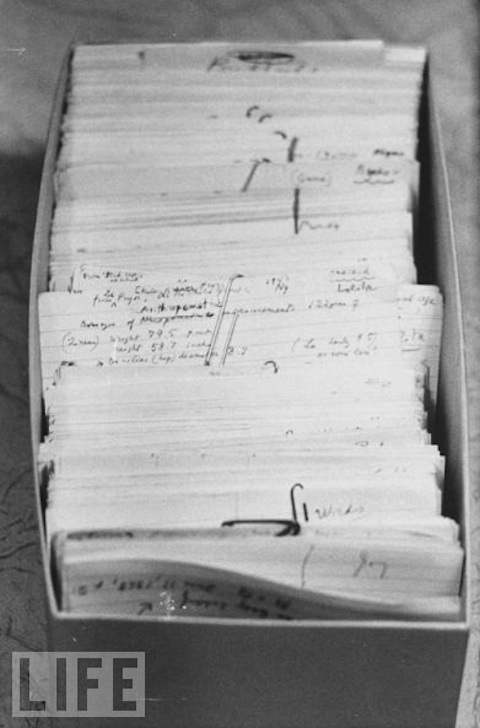

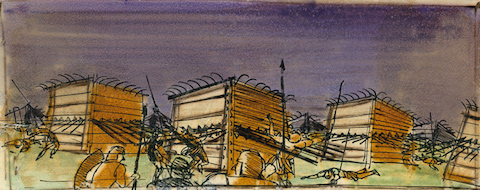

When Kubrick took a first look at Bass’ storyboards for Spartacus, as visually vivid as any of his movies themselves, he must have liked what he saw. Now you can examine them too, both at Empire and at Flavorwire’s collection of “Awesome Storyboards from 15 of Your Favorite Films.” Those of you who have watched Spartacus over and over again will recognize the look and feel sketched out (not that sketched sounds quite right for images of such a solidity unusual for storyboards) by Bass. But when the film and the drawing part ways, they do so because the plans actually came out less elaborate than the final product, not more. We see in the storyboards, as Empire says, “an elliptical sequence with the camera lingering on fragments of the fighting” with “a row of shields here, a skewered legionary there,” “but in those long-distant days when budgets went up as well as down, it was scrapped in favor of just recreating the whole thing lock, stock and flaming barrel” — very much a Kubrickian way of doing things.

Related Content:

A Brief Visual Introduction to Saul Bass’ Celebrated Title Designs

Stanley Kubrick’s List of Top 10 Films (The First and Only List He Ever Created)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.