Google Introduces 6‑Month Career Certificates, Threatening to Disrupt Higher Education with “the Equivalent of a Four-Year Degree”

Update: You can find the first of the Google Career Certificates here. They’re also added to our collection 200 Online Certificate & Microcredential Programs from Leading Universities & Companies.

I used to make a point of asking every college-applying teenager I encountered why they wanted to go to college in the first place. Few had a ready answer; most, after a deer-in-the-headlights moment, said they wanted to be able to get a job — and in a tone implying it was too obvious to require articulation. But if one’s goal is simply employment, doesn’t it seem a bit excessive to move across the state, country, or world, spend four years taking tests and writing papers on a grab-bag of subjects, and spend (or borrow) a large and ever-inflating amount of money to do so? This, in any case, is one idea behind Google’s Career Certificates, all of which can be completed from home in about six months. Find the first ones here.

Any such remote educational process looks more viable than ever at the moment due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, a condition that also has today’s college-applying teenagers wondering whether they’ll ever see a campus at all. Nor is the broader economic harm lost on Google, whose Senior Vice President for Global Affairs Kent Walker frames their Career Certificates as part of a “digital jobs program to help America’s economic recovery.” He writes that “people need good jobs, and the broader economy needs their energy and skills to support our future growth.” At the same time, “college degrees are out of reach for many Americans, and you shouldn’t need a college diploma to have economic security.”

Hence Google’s new Career Certificates in “the high-paying, high-growth career fields of Data Analytics, Project Management, and User Experience (UX) Design,” which join their existing IT Support and IT Automation in Python Certificates.

- Google UX Design Professional Certificate

- Google Data Analytics Professional Certificate

- Google Project Management Professional Certificate

- Google IT Support Professional Certificate

- Google IT Automation Professional Certificate

Hosted on the online education platform Coursera, these programs (which run about $300-$400) are developed in-house and taught by Google employees and require no previous experience. To help cover their cost Google will also fund 100,000 “need-based scholarships” and offer students “hundreds of apprenticeship opportunities” at the company “to provide real on-the-job training.” None of this guarantees any given student a job at Google, of course, but as Walker emphasizes, “we will consider our new career certificates as the equivalent of a four-year degree.”

Biggest tech & higher ed story of the last 2 weeks — #Google entering higher ed, offering BA-equivalent degrees@YahooFinance pic.twitter.com/bsGgwHsnRn

— Scott Galloway (@profgalloway) August 30, 2020

Technology-and-education pundit Scott Galloway calls that bachelor’s-degree equivalence the biggest story in his field of recent weeks. It’s perhaps the beginning of a trend where tech companies disrupt higher education, creating affordable and scalable educational programs that will train the workforce for 21st century jobs. This could conceivably mean that universities lose their monopoly on the training and vetting of students, or at least find that they’ll increasingly share that responsibility with big tech.

This past spring Galloway gave an interview to New York magazine predicting that “ultimately, universities are going to partner with companies to help them expand.” He adds: “I think that partnership will look something like MIT and Google partnering. Microsoft and Berkeley. Big-tech companies are about to enter education and health care in a big way, not because they want to but because they have to.” Whether such university partnerships will emerge as falling enrollments put the strain on certain segments of the university system remains to be seen, but so far Google seems confident about going it alone. And where Google goes, as we’ve all seen before, other institutions often follow.

Note: You can listen to Galloway elaborate on how Google may lead to the unbundling of higher ed here. Listen to the episode “State of Play: The Sharing Economy” from his Prof G podcast:

Related Content:

200 Online Certificate & Microcredential Programs from Leading Universities & Companies.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...William Blake’s Paintings Come to Life in Two Animations

The poet and painter William Blake toiled in obscurity, for the most part, and died in poverty.

Twenty some years after his death, his rebellious spirit gained traction with the Pre-Raphaelites.

By the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, Blake was ripe to be venerated as a counter-cultural hero, for having flown in the face of convention, while championing gender and racial equality, nature, and free love.

Reclining half-naked on a “a fabulous couch in Harlem,” poet Allen Ginsburg had a hallucinatory encounter wherein Blake recited to him “in earthen measure.”

Ditto poet Michael McClure, though in his case, Bob Dylan’s “Gates of Eden” served as something of a medium:

I had the idea that I was hallucinating, that it was William Blake’s voice coming out of the walls and I stood up and put my hands on the walls and they were vibrating.

Blake’s work (and world view) continues to exert enormous influence on graphic novelists, theatermakers, and creatives of every stripe.

He’s also a dab hand at animation, collaborating from beyond the grave.

The short above, a commission for a late ‘70s Blake exhibition at The Tate, envisions a roundtrip journey from Heaven to Hell. Animator Sheila Graber parked herself in the Sculpture Hall to create it in public view, pairing Blake’s line “Energy is Eternal delight” with a personal observation:

Whether we use it to create or destroy—it’s the same energy. The practice of art can turn a person from a vandal to a builder!

More recently, the Tate gave director Sam Gainsborough access to super high-res imagery of Blake’s original paintings, in order to create a promo for last year’s blockbuster exhibition.

Gainsborough and animator Renaldho Pelle worked together to bring the chosen works to life, frame by frame, against a series of London buildings and streets that were well known to Blake himself.

The film opens with Blake’s Ghost of a Flea emerging from the walls of Broadwick Street, where its creator was born, then stalking off, bowl in hand, ceding the screen to God, The Ancient of Days, whose reach spreads like ink across the gritty facade of a white brick edifice.

Seymour Milton’s original music and Jasmine Blackborow’s narration of excerpts from Blake’s poem “Auguries of Innocence” seem to anticipate the fraught current moment, as does the entire poem:

Auguries of Innocence

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

A Robin Red breast in a Cage

Puts all Heaven in a Rage

A Dove house filld with Doves & Pigeons

Shudders Hell thr’ all its regions

A dog starvd at his Masters Gate

Predicts the ruin of the State

A Horse misusd upon the Road

Calls to Heaven for Human blood

Each outcry of the hunted Hare

A fibre from the Brain does tear

A Skylark wounded in the wing

A Cherubim does cease to sing

The Game Cock clipd & armd for fight

Does the Rising Sun affright

Every Wolfs & Lions howl

Raises from Hell a Human Soul

The wild deer, wandring here & there

Keeps the Human Soul from Care

The Lamb misusd breeds Public Strife

And yet forgives the Butchers knife

The Bat that flits at close of Eve

Has left the Brain that wont Believe

The Owl that calls upon the Night

Speaks the Unbelievers fright

He who shall hurt the little Wren

Shall never be belovd by Men

He who the Ox to wrath has movd

Shall never be by Woman lovd

The wanton Boy that kills the Fly

Shall feel the Spiders enmity

He who torments the Chafers Sprite

Weaves a Bower in endless Night

The Catterpiller on the Leaf

Repeats to thee thy Mothers grief

Kill not the Moth nor Butterfly

For the Last Judgment draweth nigh

He who shall train the Horse to War

Shall never pass the Polar Bar

The Beggars Dog & Widows Cat

Feed them & thou wilt grow fat

The Gnat that sings his Summers Song

Poison gets from Slanders tongue

The poison of the Snake & Newt

Is the sweat of Envys Foot

The poison of the Honey Bee

Is the Artists Jealousy

The Princes Robes & Beggars Rags

Are Toadstools on the Misers Bags

A Truth thats told with bad intent

Beats all the Lies you can invent

It is right it should be so

Man was made for Joy & Woe

And when this we rightly know

Thro the World we safely go

Joy & Woe are woven fine

A Clothing for the soul divine

Under every grief & pine

Runs a joy with silken twine

The Babe is more than swadling Bands

Throughout all these Human Lands

Tools were made & Born were hands

Every Farmer Understands

Every Tear from Every Eye

Becomes a Babe in Eternity

This is caught by Females bright

And returnd to its own delight

The Bleat the Bark Bellow & Roar

Are Waves that Beat on Heavens Shore

The Babe that weeps the Rod beneath

Writes Revenge in realms of Death

The Beggars Rags fluttering in Air

Does to Rags the Heavens tear

The Soldier armd with Sword & Gun

Palsied strikes the Summers Sun

The poor Mans Farthing is worth more

Than all the Gold on Africs Shore

One Mite wrung from the Labrers hands

Shall buy & sell the Misers Lands

Or if protected from on high

Does that whole Nation sell & buy

He who mocks the Infants Faith

Shall be mockd in Age & Death

He who shall teach the Child to Doubt

The rotting Grave shall neer get out

He who respects the Infants faith

Triumphs over Hell & Death

The Childs Toys & the Old Mans Reasons

Are the Fruits of the Two seasons

The Questioner who sits so sly

Shall never know how to Reply

He who replies to words of Doubt

Doth put the Light of Knowledge out

The Strongest Poison ever known

Came from Caesars Laurel Crown

Nought can Deform the Human Race

Like to the Armours iron brace

When Gold & Gems adorn the Plow

To peaceful Arts shall Envy Bow

A Riddle or the Crickets Cry

Is to Doubt a fit Reply

The Emmets Inch & Eagles Mile

Make Lame Philosophy to smile

He who Doubts from what he sees

Will neer Believe do what you Please

If the Sun & Moon should Doubt

Theyd immediately Go out

To be in a Passion you Good may Do

But no Good if a Passion is in you

The Whore & Gambler by the State

Licencd build that Nations Fate

The Harlots cry from Street to Street

Shall weave Old Englands winding Sheet

The Winners Shout the Losers Curse

Dance before dead Englands Hearse

Every Night & every Morn

Some to Misery are Born

Every Morn and every Night

Some are Born to sweet delight

Some are Born to sweet delight

Some are Born to Endless Night

We are led to Believe a Lie

When we see not Thro the Eye

Which was Born in a Night to perish in a Night

When the Soul Slept in Beams of Light

God Appears & God is Light

To those poor Souls who dwell in Night

But does a Human Form Display

To those who Dwell in Realms of day

Related Content:

William Blake’s Masterpiece Illustrations of the Book of Job (1793–1827)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

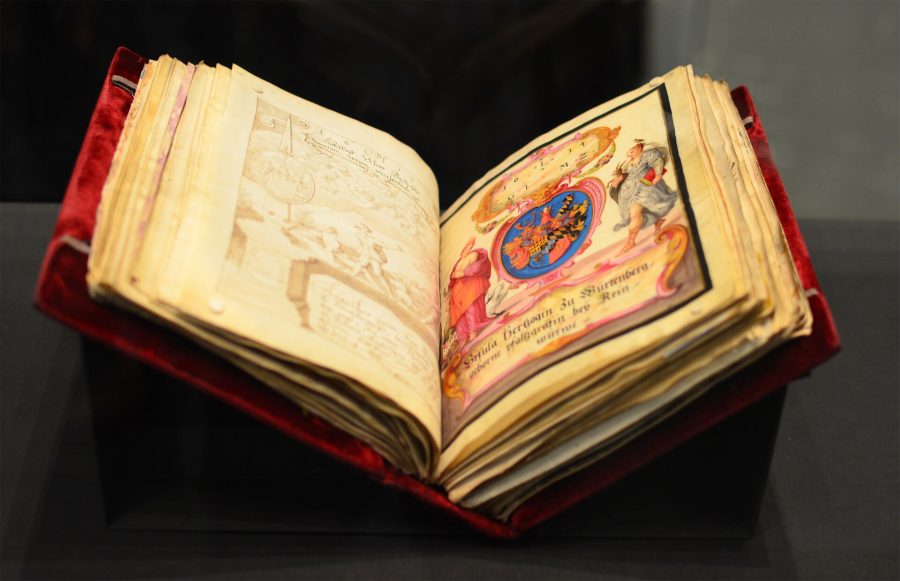

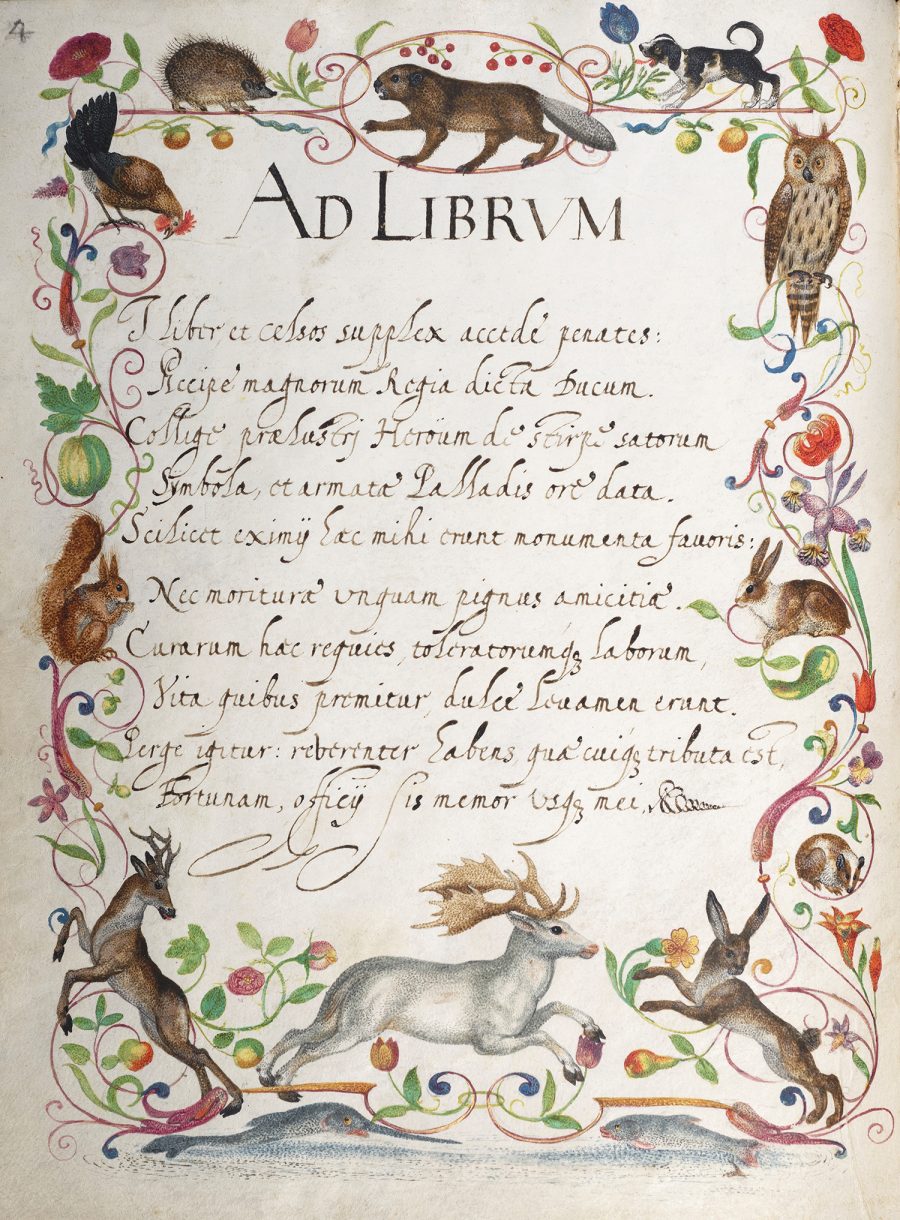

Read More...Behold a Beautiful 400-Year-Old ‘Friendship Book’ Featuring the Signatures of Historic Figures

Maintaining the balance of power among European states has always been a fraught affair, but it was especially so in the years when mercantilism made fragile alliances during the religious wars of the 17th century. This was a time when merchants made excellent diplomats, not only because they traveled extensively and learned foreign tongues and customs, but because they spoke the universal language of trade.

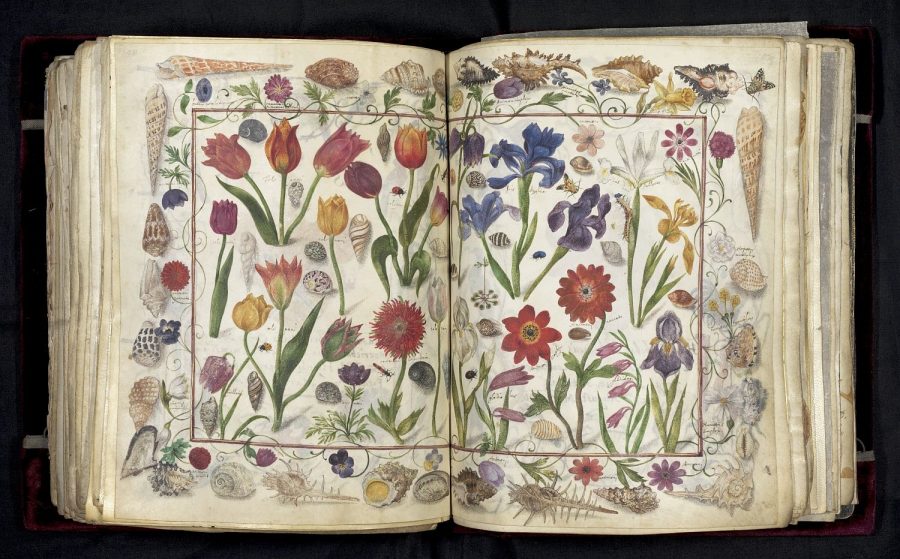

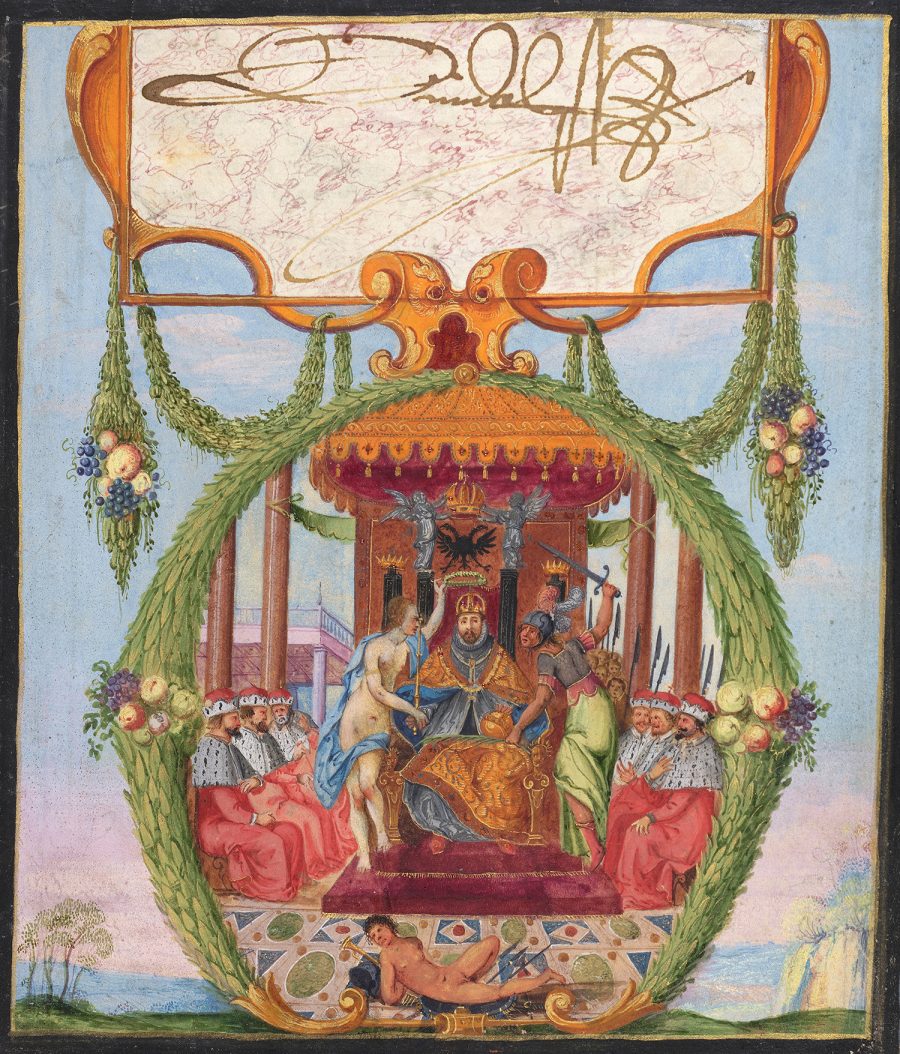

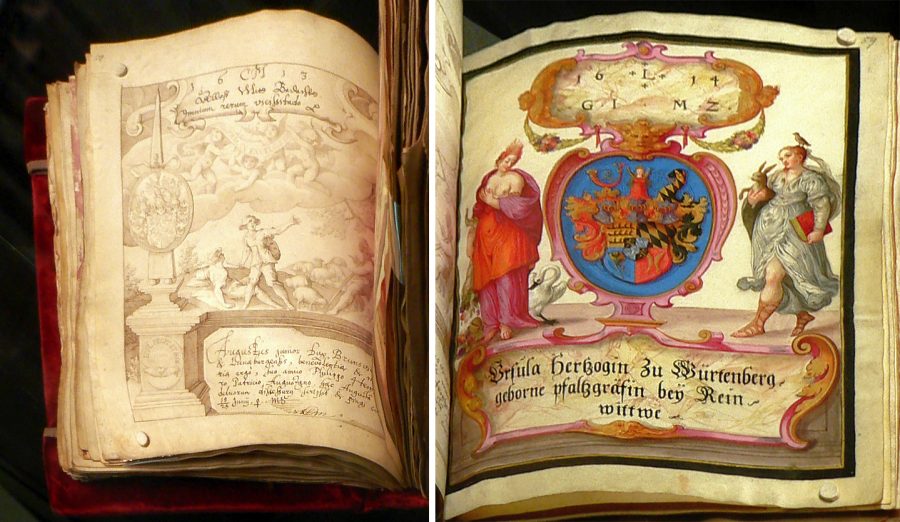

German merchant and diplomat Philipp Hainhofer from Augsburg was such a figure, traveling from court to court to meet with Europe’s renowned dignitaries. As he did so, he would ask them to sign his album amicorum, or “friendship book,” also called a stammbuch. Each signer would then “commission an artist to create a painting accompanying their signatures,” Alison Flood writes at The Guardian.

“There are around 100 drawings” in his autograph book, known as the Große Stammbuch, “which took more than 50 years to compile.” After Hainhofer’s death in 1647, his friend August the Younger—who helped collect the hundreds of thousand of books in the Herzog August Bibliothek—tried to acquire the book but failed. Now it has finally landed in the huge library, one of the world’s oldest, almost 400 years later, after a purchase at a private auction this week.

Friendship books were commonly used at the time to record the names of family and friends. Students used them as yearbooks, and Hainhofer began his collection of signatures as a college student. He gradually gained a select clientele as his career advanced. Signatories, the History Blog points out, “include Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, another HRE Matthias, Christian IV of Denmark and Norway, Cosimo II de’Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany…” and many others.

Hainhofer’s Große Stammbuch is, as you can see, a beautiful work of art—or almost 100 collected works of art—in its own right. “The elaborateness of the illustrations directly corresponds to the signatory’s status and rank in society,” as Grace Ebert notes at Colossal. It is also a fascinating record of Early Modern European politics, trade, and diplomacy, a fine art all its own.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

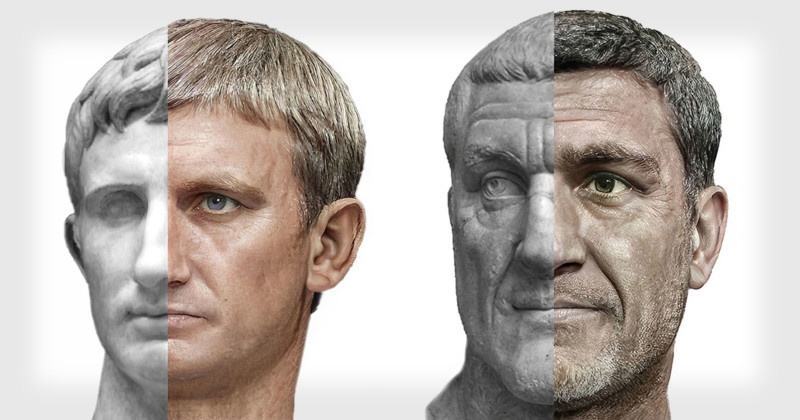

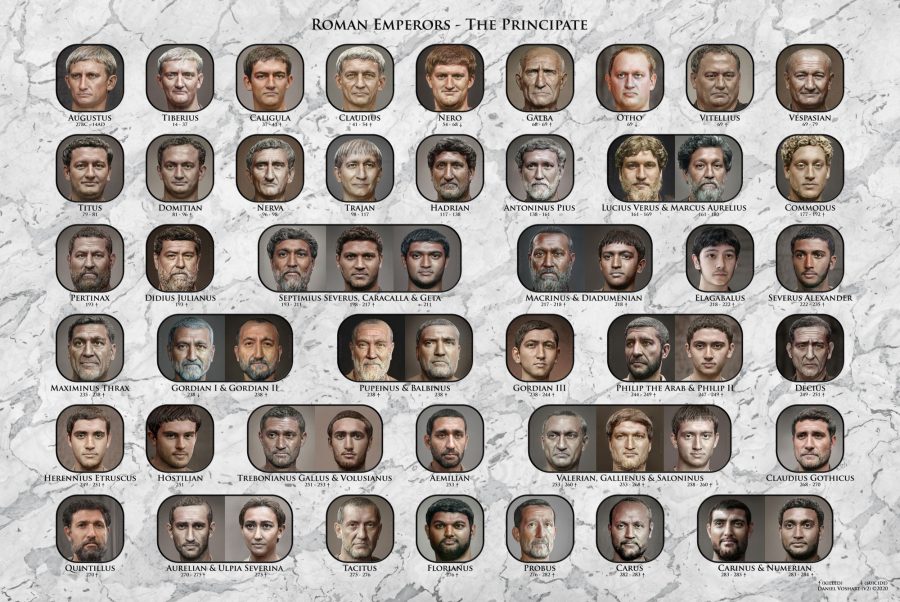

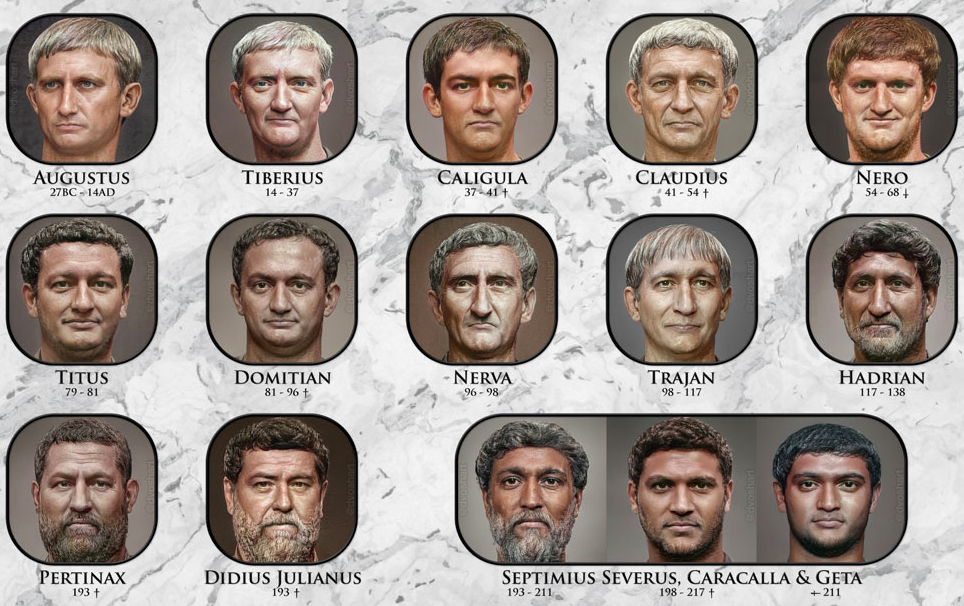

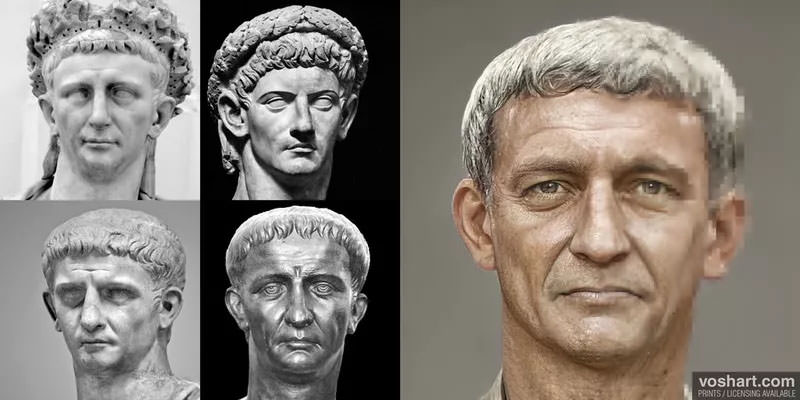

Read More...What Did the Roman Emperors Look Like?: See Photorealistic Portraits Created with Machine Learning

We can spend a lifetime reading histories of ancient Rome without knowing what any of its emperors looked like. Or rather, without knowing exactly what they looked like: being the leaders of the mightiest political entity in the Western world, they had their likenesses stamped onto coins and carved into busts as a matter of course. But such artist’s renderings inevitably come with a certain degree of artistic license, a tendency to mold features into slightly more imperial shapes. Seeing the faces of the Roman Emperors as we would if we were passing them on the street is an experience made possible only by high technology, and high technology developed sixteen centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire at that.

“Using the neural-net tool Artbreeder, Photoshop and historical references, I have created photoreal portraits of Roman Emperors,” writes designer Daniel Voshart. “For this project, I have transformed, or restored (cracks, noses, ears etc.) 800 images of busts to make the 54 emperors of The Principate (27 BC to 285 AD).”

The key technology that enables Artbreeder to convincingly blend images of faces together is what’s called a “generative adversarial network” (GAN). “Some call it Artificial Intelligence,” writes Voshart, “but it is more accurately described as Machine Learning.” The Verge’s James Vincent writes that Voshart fed in “images of emperors he collected from statues, coins, and paintings, and then tweaked the portraits manually based on historical descriptions, feeding them back to the GAN.”

Into the mix also went “high-res images of celebrities”: Daniel Craig into Augustus, André the Giant into Maximinus Thrax (thought to have been given his “a lantern jaw and mountainous frame” by a pituitary gland disorder like that which affected the colossal wrestler). This partially explains why some of these uncannily lifelike emperors — the biggest celebrities of their time and place, after all — look faintly familiar. Though modeled as closely as possible after men who really lived, these exact faces (much like those in the artificial intelligence-generated modern photographs previously featured here on Open Culture) have never actually existed. Still, one can imagine the emperors who inspired Voshart’s Principate recognizing themselves in it. But what would they make of the fact that it’s also selling briskly in poster form on Etsy?

Visit the Roman Emperor Project here. For background on this project, visit here.

Related Content:

Five Hardcore Deaths Suffered By Roman Emperors

Play Caesar: Travel Ancient Rome with Stanford’s Interactive Map

Rome Reborn: Take a Virtual Tour of Ancient Rome, Circa 320 C.E.

The History of Ancient Rome in 20 Quick Minutes: A Primer Narrated by Brian Cox

The History of Rome in 179 Podcasts

Roman Statues Weren’t White; They Were Once Painted in Vivid, Bright Colors

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...2020: An Isolation Odyssey–A Short Film Reenacts the Finale of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, with a COVID-19 Twist

From New York City designer Lydia Cambron comes 2020: An Isolation Odyssey, a short film that reenacts the finale of Stanley Kubrick’s iconic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. But with a COVID-19 twist. “Restaged in the context of home quarantine,” Cambron writes, “the journey through time adapts to the mundane dramas of self-isolation–poking fun at the navel-gazing saga of life alone and indoors.” If you’ve been a good citizen since March, you will surely get the joke.

Related Content:

Watch the Opening of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey with the Original, Unused Score

James Cameron Revisits the Making of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey

Rare 1960s Audio: Stanley Kubrick’s Big Interview with The New Yorker

Read More...Ballerina Misty Copeland Recreates the Poses of Edgar Degas’ Ballet Dancers

“I am a man of motion,” tragic modernist ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky wrote in his famous Diary, “I am feeling through flesh…. I am God in a body.” Nijinsky suffered the unfortunate onset of schizophrenia after his career ended, but in his lucid moments, he writes of the greatest pain of his illness—to never dance again. A degree of his obsessive devotion seems intrinsic to ballet.

Misty Copeland, who titled her autobiography Life in Motion, thinks so. “All dancers are control freaks a bit,” she says. “We just want to be in control of ourselves and our bodies. That’s just what the ballet structure, I think, kind of puts inside of you. If I’m put in a situation where I am not really sure what’s going to happen, it can be overwhelming. I get a bit anxious.” As Nijinsky did, Copeland is also “forcing people to look at ballet through a more contemporary lens,” writes Stephen Mooallem in Harper’s Bazaar.

Copeland has been candid about her struggles on the way to becoming the first African American woman named a principal dancer at the American Ballet Theatre, including coping with depression, a leg-injury, body-image issues, and childhood poverty. She is also “in the midst of the most illuminating pas de deux with pop culture for a classical dancer since Mikhail Baryshnikov went toe-to-toe with Gregory Hines in White Nights” (a reference that may be lost on younger readers, but trust me, this was huge).

Like another modernist artist, Edgar Degas, Copeland has revolutionized the image of the ballet dancer. Degas’ ballet paintings, “which the artist began creating in the late 1860s and continued making until the years before his death, in 1917, were infused with a very modern sensibility. Instead of idealized visions of delicate creatures pirouetting onstage, he offered images of young girls congregating, practicing, laboring, dancing, training….” He showed the unglamorous life and work behind the costumed pageantry, that is.

Photographers Ken Browar and Deborah Ory envisioned Copeland as several of Degas’ dancers, posing her in couture dresses in recreations of some of his famous paintings and sculptures. The photographs are part of their NYC Dance Project, in partnership with Harper’s Bazaar. As Kottke points out, conflating the histories of Copeland and Degas’ dancers raises some questions. Degas had contempt for women, especially his Parisian subjects, who danced in a sordid world in which “sex work” between teenage dancers and older men “was a part of a ballerina’s reality,” writes author Julia Fiore (as it was too in Nijinsky’s day).

This context may unsettle our viewing, but the images also show Copeland in full control of Degas’ scenes, though that’s not the way it felt, she says. “It was interesting to be on shoot and to not have the freedom to just create like in normally do with my body. Trying to re-create what Degas did was really difficult.” Instead, she embodied his figures as herself. “I see a great affinity between Degas’s dancers and Misty,” says Thelma Golden, director of the Studio Museum in Harlem. “She has knocked aside a long-standing music-box stereotype of the ballerina and replaced it with a thoroughly modern, multicultural image of presence and power.”

See more of Copeland’s Degas recreations at Harper’s Bazaar.

Related Content:

Impressionist Painter Edgar Degas Takes a Stroll in Paris, 1915

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Historic Mexican Recipes Are Now Available as Free Digital Cookbooks: Get Started With Dessert

There are too many competing stories to tell about the pandemic for any one to take the spotlight for long, which makes coming to terms with the moment especially challenging. Everything seems in upheaval—especially in parts of the world where rampant corruption, ineptitude, and authoritarian abuse have worsened and prolonged an already bad situation. But if there’s a lens that might be wide enough to take it all in, I’d wager it’s the story of food, from manufacture, to supply chains, to the table.

The ability to dine out serves as a barometer of social health. Restaurants are essential to normalcy and neighborhood coherence, as well as hubs of local commerce. They now struggle to adapt or close their doors. Food service staff represent some of the most precarious of workers. Meanwhile, everyone has to eat. “Some of the world’s best restaurants have gone from fine dining to curbside pickups,” writes Rico Torres, Chef and Co-owner of Mixtli. “At home, a renewed sense of self-reliance has led to a resurgence of the home cook.”

Some, amateurs and professionals both, have returned their skills to the community, cooking for protestors on the streets, for example. Others have turned a newfound passion for cooking on their families. Whatever the case, they are all doing important work, not only by feeding hungry bellies but by engaging with and transforming culinary traditions. Despite its essential ephemerality, food preserves memory, through the most memory-intensive of our senses, and through recipes passed down for generations.

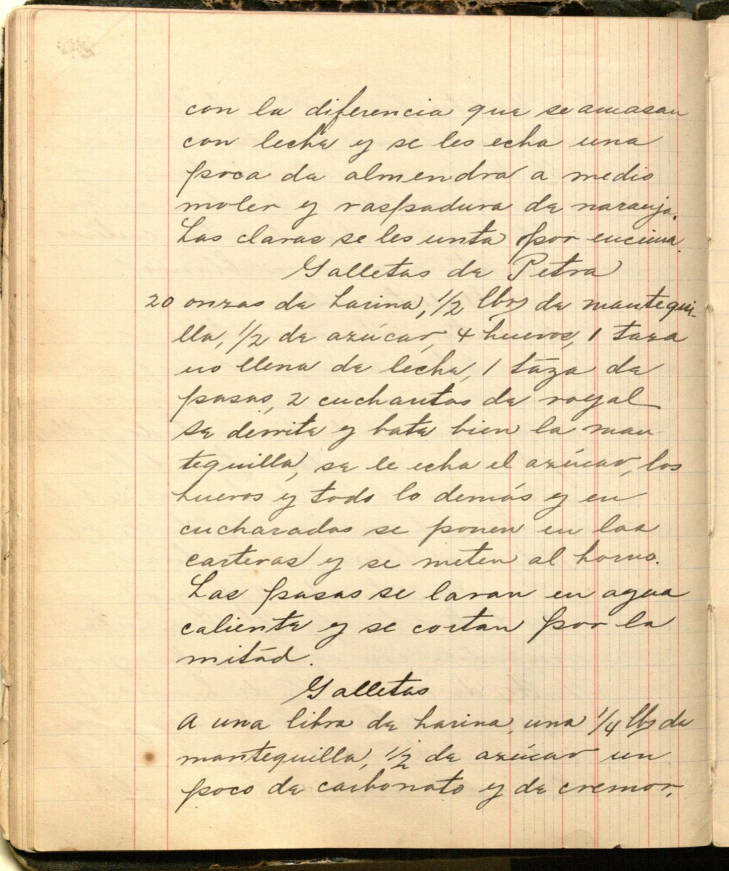

Recipe collections are also sites of cultural exchange and conflict. Such has been the case in the long struggle to define the essence of authentic Mexican food. You can learn more about that argument in our previous post on a collection of traditional (and some not-so-traditional) Mexican cookbooks which are being digitized and put online by researchers at the University of Texas San Antonio (UTSA). Their collection of over 2,000 titles dates from 1789 to the present and represents a vast repository of knowledge for scholars of Mexican cuisine.

But let’s be honest, what most of us want, and need, is a good meal. It just so happens, as chefs now serving curbside will tell you, that the best cooking (and baking) learns from the cooking of the past. In observance of the times we live in, the UTSA Libraries Special Collections has curated many of the historic Mexican recipes in their collection as what they call “a series of mini-cookbooks” titled “Recetas: Cocindando en los Tiempos del Coronavirus.”

Because many in our communities have found themselves in the kitchen during the COVID-19 pandemic during stay-at-home orders, we hope to share the collection and make it even more accessible to those looking to explore Mexican cuisine.

These recipes, now being made available as e‑cookbooks, have been transcribed and translated from handwritten manuscripts by archivists who are passionate about this food. Perhaps in honor of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate—whose novel “paints a narrative of family and tradition using Mexico’s deep connection to cuisine”—the collection has “saved the best for first” and begun with the dessert cookbook. They’ll continue the reverse order with Volume 2, main courses, and Volume 3, appetizers & drinks.

Endorsed by Chef Torres, the first mini-cookbook modernizes and translates the original Spanish into English, and is available in pdf or epub. It does not modernize more traditional ways of cooking. As the Preface points out, “many of the manuscript cookbooks of the early 19th century assume readers to be experienced cooks.” (It was not an occupation undertaken lightly.) As such, the recipes are “often light on details” like ingredient lists and step-by-step instructions. As Atlas Obscura notes, the recipe above for “ ‘Petra’s cookies’ calls for “‘one cup not quite full of milk.’ ”

“We encourage you to view these instructions as opportunities to acquire an intuitive feel for your food,” the archive writes. It’s good to learn new habits. Whatever else it is now—community service, chore, an exercise in self-reliance, self-improvement, or stress relief—cooking is also creating new ways of remembering and connecting across new distances of time and space, working with the raw materials we have at hand. Download the first Volume of the UTSA cookbook series, Postres: Guardando Lo Mejor Para el Principio, here and look for more “Cooking in the Time of Coronavirus” recipes coming soon.

Related Content:

An Archive of Handwritten Traditional Mexican Cookbooks Is Now Online

An Archive of 3,000 Vintage Cookbooks Lets You Travel Back Through Culinary Time

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Banksy Strikes Again in London & Urges Everyone to Wear Masks

The person who may or may not be Banksy is at it again, this time stenciling up a London Underground carriage with his familiar rat characters. Rats know a thing or two about spreading disease but this time they are here to insist that the public wear a mask. (Earlier in April they appeared in the artist’s own bathroom.)

As posted on Banksy’s social media feeds on Tuesday we can see the artist get kitted up like one of the Underground’s “deep cleaners”—-a protective face mask, goggles, blue gloves, white Tyvek bodysuit, and orange safety vest—and enter a carriage with an exterminator’s spray canister filled with light blue paint. He also has some of his stencils ready to go. “If you don’t mask, you don’t get” reads the video’s caption.

Currently all passengers must wear masks on the London Underground, and over the last month Transport for London has reported a 90% compliance rate (take note, America!). Workers have been sanitizing stations and trains more, and even installing UV light technology to battle the virus.

Banksy’s rats are shown using masks as parachutes, carrying bottles of hand sanitizer, and along one wall sneezing particles across the window, painted using the canister spray nozzle. Bansky tags the back wall with his name, urges a passenger to stay back while he works, and then gets off at a stop. He’s left one final message: “I get lockdown” (painted on a station wall) “but I get up again” (on the closing doors). The line is a nod to Chumbawumba’s inescapable 1997 anthem “Tubthumping.”

Banksy might be a rebellious street artist, but he’s not an idiot: wearing masks is imperative.

The artwork didn’t last long, as Transport of London has strict policies against graffiti. So few passengers even got to experience the art before it was scrubbed by workers, long before anybody would have identified it as a Banksy work.

“When we saw the video, we started to look into it and spoke to the cleaners,” a London Transport source told the New York Post. “It started to emerge that they had noticed some sort of ‘rat thing’ a few days ago and cleaned it off, as they should. It rather changes the aspect for anyone seeking to go down the route of accusing us of cultural vandalism.”

The Post even suggested that the carriage could have been removed and then sold as a complete art work in itself and raised money for charity. (They quote an art broker who values it at $7.5 million. But where would you hang it? In your private airplane hanger?)

Anyway, like a lot of Banksy work, it appeared, it was documented, and it was gone. Transport of London did mention that they were open to Banksy creating something else at a “suitable location,” but then again, that’s not how the artist rolls. Just keep your eyes open, folks, and look out for rats.

Related Content:

Behind the Banksy Stunt: An In-Depth Breakdown of the Artist’s Self-Shredding Painting

Banksy Strikes Again in Venice

Banksy Paints a Grim Holiday Mural: Season’s Greetings to All

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

Read More...A Free Stanford Course on How to Teach Online: Designed for Middle & High School Teachers (July 13 — 17)

This fall, many teachers (across the country and the world) will be asked to teach online–something most teachers have never done before. To assist with that transition, the Stanford Online High School and Stanford Continuing Studies have teamed up to offer a free online course called Teaching Your Class Online: The Essentials. Taught by veteran instructors at Stanford Online High School (OHS), this course “will help middle and high school instructors move from general concepts for teaching online to the practical details of adapting your class for your students.” The course is free and runs from 1–3 pm California time, July 13 — 17. You can sign up here.

For anyone interested, Stanford will also offer additional courses that give teachers the chance to practice teaching their material online and get feedback from Stanford Online High School instructors. Offered from July 20 — July 24, those courses cost $95. Click to this page, and scroll down to enroll.

Related Content:

1,500 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

“I Will Survive,” the Coronavirus Version for Teachers Going Online

Read More...Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #49 Considers Conspiracy Theories as Pop

Ex-philosopher Al Baker works at the UK-based Logically, a company that fights misinformation.

He joins your hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt to try to answer such questions as: What’s the appeal of conspiracy theories? How similar is being consumed them to being a die-hard fan of some pop culture property? What’s the relation between pernicious conspiracy theories and fun speculation (like, maybe Elvis is alive)? Is there a harmless way to engage in conspiracy theorizing as a hobby? Is something still a conspiracy theory in the pejorative sense if it turns out to be true?

We touch on echo chambers, the role of irony and humor in spreading these theories, how both opponents and proponents claim to be skeptics, Dan Brown Novels, Tom Hanks, the Mel Gibson film Conspiracy Theory, and documentaries like Behind the Curve (about Flat Earthers) and The Family.

For expert opinions on the psychology of conspiracy theories, try The Conversation’s Antill Podcast, which had a whole series on this topic. For even more podcast action, try FiveThirtyEight, BBC’s The Why Factor podcast, Skeptoid, and The Infinite Monkey Cage.

Here are some more articles:

- “Why We Should Not Treat All Conspiracy Theories the Same” by Jaron Harambam

- “We’re Keeping A Running List Of Hoaxes And Misleading Posts About The Nationwide Police Brutality Protests” by Jane Lytvyneko and Craig Silverman

- “The Greatest Celebrity Conspiracy Theories of All Time” by Matt Miller

- “My Father, the QAnon Conspiracy Theorist” by Reed Ryley Grable

- “COVID-19 and the Turn to Magical Thinking” by Hugh Gusterson

- A new podcast called Wind of Change claims that the CIA wrote the Scorpions song by that name.

If you enjoy this, try Pretty Much Pop #14 on UFOs. The Partially Examined Life episodes referred to in this discussion are #96 on Oppenheimer and the Rhetoric of Science Advisers and #82 on Karl Popper.

Learn more at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode.

Read More...