What kind of delusional self-aggrandizer, called to testify before a United States Senate Subcommittee, uses it as an opportunity to quote the lyrics of a song he’s written… in their entirety!?

Sounds like the work of a certain rapper/prospective political candidate or perhaps some daffy buffoon as brought to life by Ben Stiller or Will Ferrell.

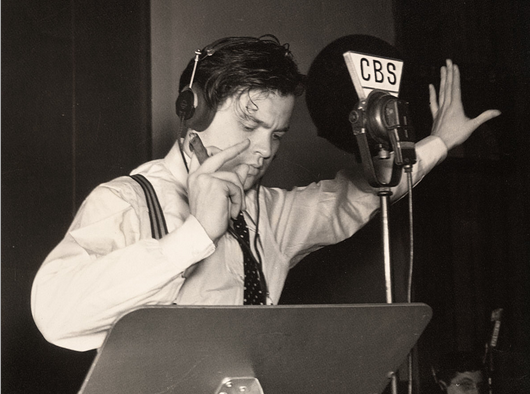

Only children’s television host Fred Rogers could pull such a stunt and emerge unscathed, nay, even more beloved, as he does above in documentary footage from 1969.

Mister Rogers’ impulse to recite What Do You Do With the Mad That You Feel to then-chairman of the Subcommittee on Communications, Senator John Pastore, was ultimately an act of service to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and its child viewers.

Newly elected President Richard Nixon opposed public television, believing that its liberal bent could only undermine his administration. Determined to strike first, he proposed cuts equal to half its $20 million annual operating budget, a measure that would have seriously hobbled the fledgling institution.

Mr. Rogers appeared before the Committee armed with a “philosophical statement” that he refrained from reading aloud, not wishing to monopolize ten minutes of the Committee’s time. Instead, he sought Pastore’s promise that he would give it a close read later, speaking so slowly and with such little outward guile, that the tough nut Senator was moved to crack, “Would it make you happy if you did read it?”

Rather than taking the bait, Rogers touched on the ways his show’s budget had grown thanks to the public broadcasting model. He also hipped Pastore to the qualitative difference between frenetic kiddie cartoons and the vastly more thoughtful and emotionally healthy content of programming such as his. Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood was a place where such topics as haircuts, sibling relationships, and angry feelings could be discussed in depth.

Rogers’ emotional intelligence seems to hypnotize Pastore, whose challenging front was soon dropped in favor of a more respectful line of questioning. By the end of Rogers’ heartfelt, non-musical rendition of What Do You Do… (it’s much peppier in the original), Pastore has goosebumps, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting has its 2 mil’ back in the bag.

What do you do with the mad that you feel

When you feel so mad you could bite?

When the whole wide world seems oh, so wrong…

And nothing you do seems very right?

What do you do? Do you punch a bag?

Do you pound some clay or some dough?

Do you round up friends for a game of tag?

Or see how fast you go?

It’s great to be able to stop

When you’ve planned a thing that’s wrong,

And be able to do something else instead

And think this song:

I can stop when I want to

Can stop when I wish.

I can stop, stop, stop any time.

And what a good feeling to feel like this

And know that the feeling is really mine.

Know that there’s something deep inside

That helps us become what we can.

For a girl can be someday a woman

And a boy can be someday a man.

Related Content:

Mr. Rogers Takes Breakdancing Lessons from a 12-Year-Old (1985)

Puppet Making with Jim Henson: A Priceless Primer from 1969

Ayun Halliday’s new play, Fawnbook, debuts as part of the Bad Theater Festival in NYC tomorrow night. Follow her @AyunHalliday