I first encountered bongo-playing physicist Richard Feynman in a college composition class geared toward science majors. I was not, mind you, a science major, but a disorganized sophomore who registered late and grabbed the last available seat in a required writing course. Skeptical, I thumbed through the reading in the college bookstore. As I browsed Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!—the first of many popular memoirs released by the affable contrarian scientist—the humanist in me perked up. Here was a guy who knew how to write; a theoretical physicist who spoke the language of everyday people.

Feynman cultivated his populist persona to appeal to those who might be otherwise turned off by abstract, abstruse scientific concepts. Like Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson, his name has come to stand for the best examples of popular science communication. It is often through one of Feynman’s accessible, non-specialist books or presentations that people learn of his work with the Manhattan project, his contributions to quantum mechanics, and his Nobel Prize. But Feynman’s extracurricular pursuits—from safe-cracking to drumming to experimenting with LSD—were also genuine expressions of his idiosyncratic character, as was another of his passions for which he is not very well known: art.

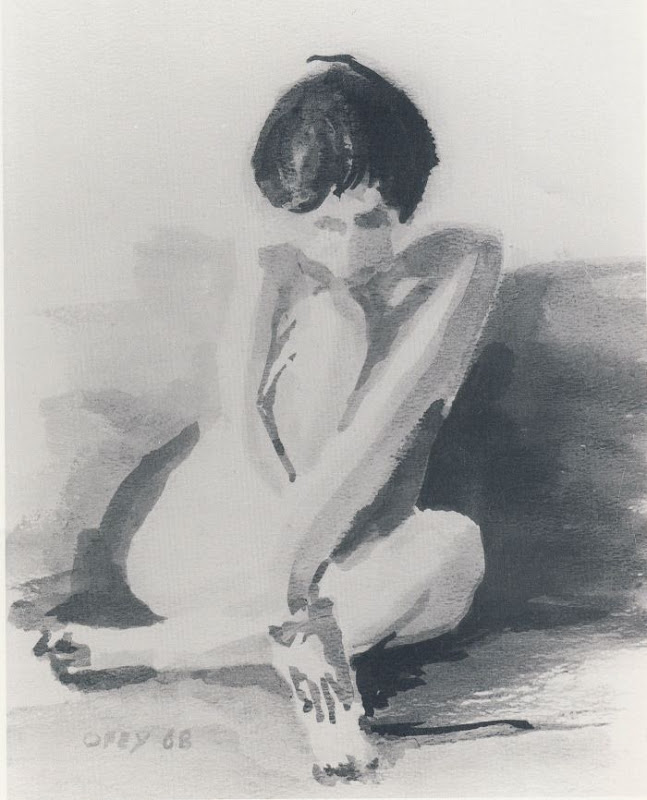

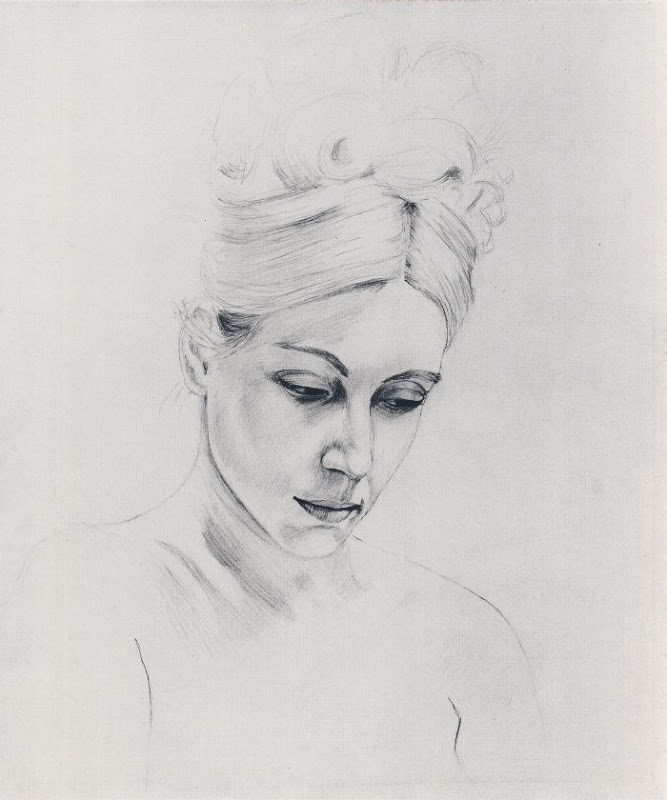

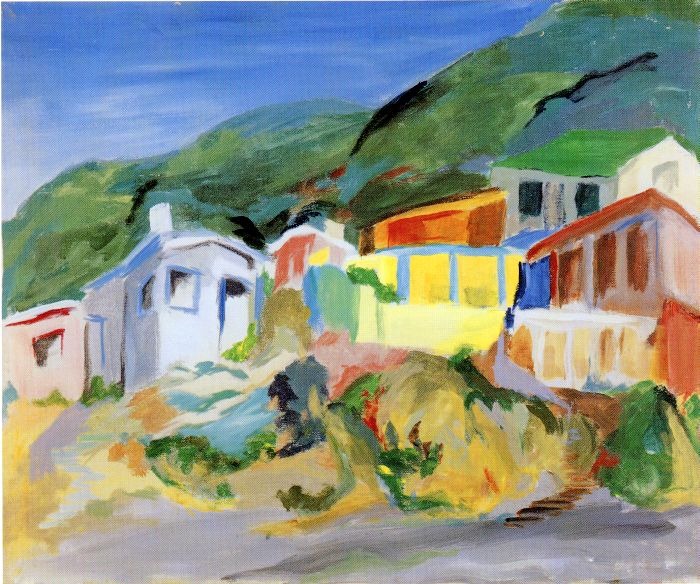

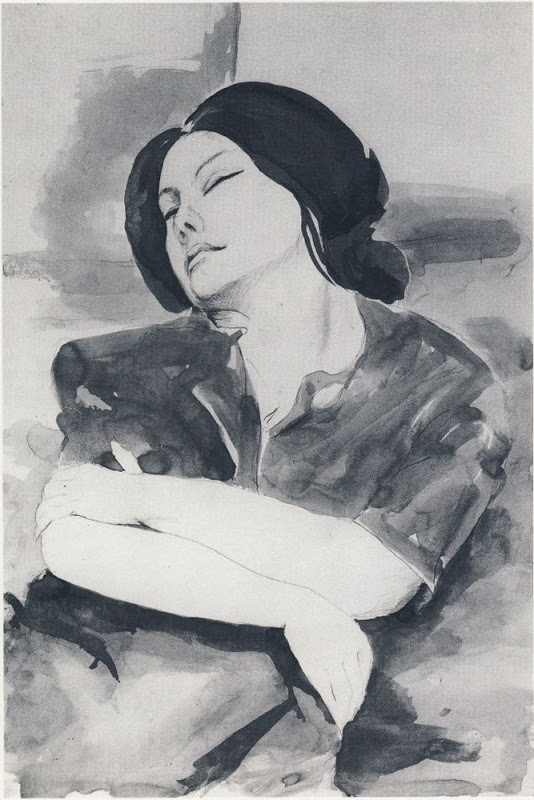

Feynman took up the pursuit at the age of 44, and continued to draw and paint for the rest of his life, signing his work “Ofey.” Many of his drawings display the awkward, off-kilter perspective of the beginner, and a great many others look very accomplished indeed. In an introductory essay to a published collection of his artwork, Feynman describes what motivated him to take up this particular avocation:

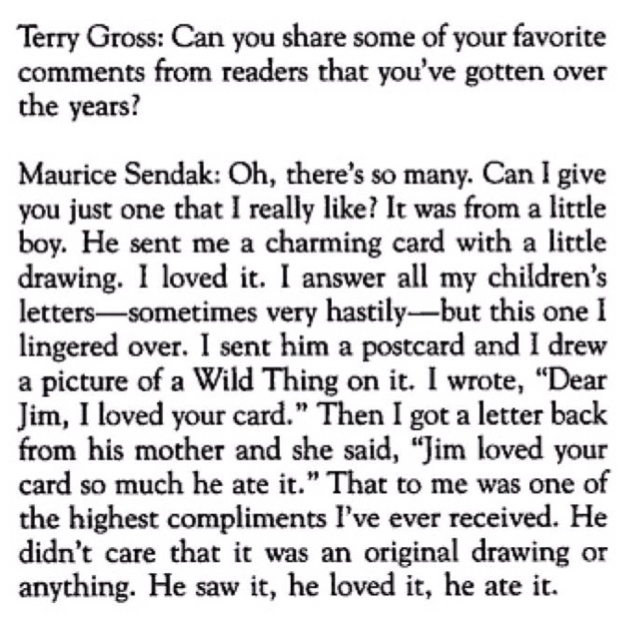

I wanted very much to learn to draw, for a reason that I kept to myself: I wanted to convey an emotion I have about the beauty of the world. It’s difficult to describe because it’s an emotion. It’s analogous to the feeling one has in religion that has to do with a god that controls everything in the universe: there’s a generality aspect that you feel when you think about how things that appear so different and behave so differently are all run ‘behind the scenes’ by the same organization, the same physical laws. It’s an appreciation of the mathematical beauty of nature, of how she works inside; a realization that the phenomena we see result from the complexity of the inner workings between atoms; a feeling of how dramatic and wonderful it is. It’s — of scientific awe — which I felt could be communicated through a drawing to someone who had also had that emotion. I could remind him, for a moment, of this feeling about the glories of the universe.

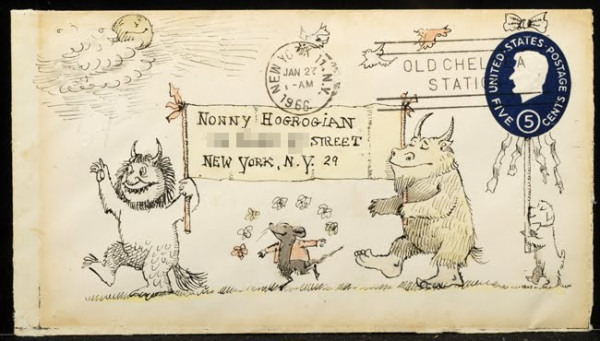

As you can see above, he took his work seriously. Most of his drawings consist of portraits and nudes, with the occasional landscape or still life. You can see more extensive galleries of Feynman’s art at AmusingPlanet, Museum Syndicate and Brain Pickings.

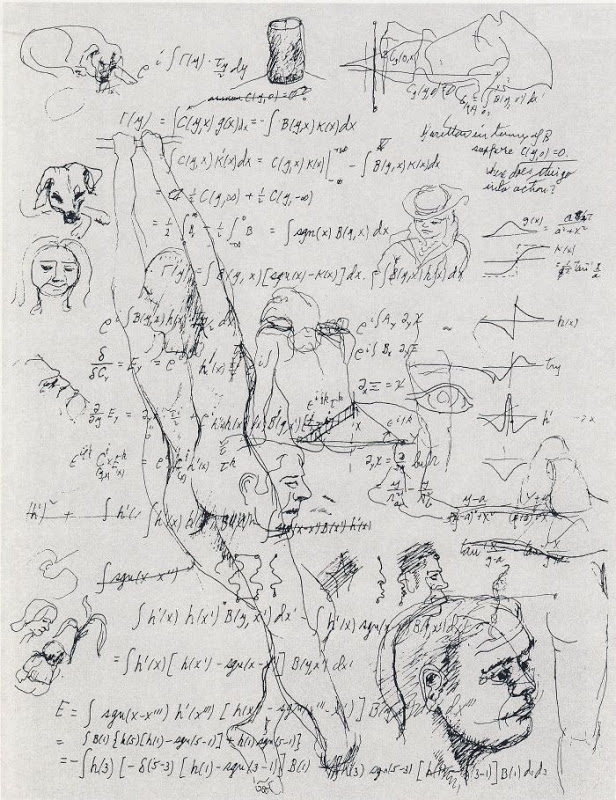

Feynman’s preoccupation—and full immersion—in the relationship between the arts and sciences marks him as a Renaissance man in perhaps the purest definition of the term: his approach closely resembles that of Leonardo da Vinci, a likeness that comes to the fore in the work below, which is either a collection of sketches doodled over with formulae, or a collection of formulae covered with doodles. Either way, it’s a perfect representation of the visionary mind of Feynman and his regard for ordinary language, people, and objects—and for “scientific awe.”

Related Content:

Learn How Richard Feynman Cracked the Safes with Atomic Secrets at Los Alamos

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness