Just a quick reminder, Martin Scorsese’s two-part documentary on George Harrison airs tonight and tomorrow night on HBO. After making films about Bob Dylan and The Rolling Stones, the legendary filmmaker now turns somewhat unexpectedly to the silent Beatle, and you have to wonder why. Why George? So Scorsese recalls when things originally clicked, the first moment when he realized the “picture had to be made.”

Kickstarter: the Future of Self-Publishing?

We all know where books come from: a human and a muse meet, fall in love, and two months to twenty years later, a book is born. Then, as with other varieties of babies, the sleepless nights start as a writer searches for a home for the book, collecting rejections like badges of honor, testaments to determination.

We all know where books come from: a human and a muse meet, fall in love, and two months to twenty years later, a book is born. Then, as with other varieties of babies, the sleepless nights start as a writer searches for a home for the book, collecting rejections like badges of honor, testaments to determination.

Well, that was the old-fashioned way. We’ve all heard how the internet has leveled the playing field, allowing anybody to publish work and find an audience. However, this easier path to publication hasn’t necessarily solved an even older writer’s conundrum: How to pay for it.

That is, how to make enough money to sustain yourself as you write (day jobs aside). And so writers must become even wilier. Though you may make money from the sale of a book, how do you fund yourself before the book?

Seth Harwood, the author of three books, is at the front of the movement to find alternate and creative ways of not only reaching audiences, but pursuing the writing life. Since graduating from the Iowa Writers Workshop in 2002, Harwood has built up a loyal fan base—his “Palms Mamas and Palms Daddies” (named for one of his protagonists, Jack Palms)—through social media and free podcasting. Harwood is sustaining a writing life along a path that is likely to be more and more common for writers.

After offering his first novel, Jack Wakes Up, as a free audiobook, Harwood published it in paperback with Breakneck Books in 2008. The Amazon sales, pushed by Palms Mamas and Palms Daddies, landed the book in #1 in Crime/Mystery and #45 overall, bringing the attention of Random House, who re-published the book one year later.

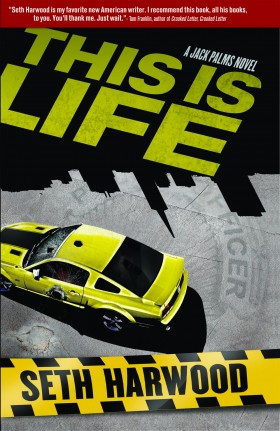

Looking outside mainstream avenues, Harwood secured funding for publication of his next venture, Young Junius, with Tyrus Books by preselling signed copies through Paypal—before the books existed in physical form. And now he is one of the early adopters of using Kickstarter to pay for the gestation and birth of not one book—but five previously-written works in the next six months–as he puts it, “raising the fixed costs of bringing these books to the marketplace.” His Kickstarter campaign based around This Is Life, the sequel to Jack Wakes Up was—impressively—fully funded within 25 hours—and with a few days still left to go, it has exceeded the original goal by over $2000.

What can a writer offer besides an autographed copy of the to-be-written book, or a mention in the acknowledgements? For Harwood’s project, the pledges range from a dollar to $999, with thank-yous spanning from the aforementioned to—at the $999 end—an original novella written according to the donor’s wishes and published as a one-off hardcover.

As more and more writers become cynical about the mainstream publishing industry, and the limits it places on writers, and as the internet breaks down barriers between writers and readers, alternate paths of drawing audiences to the writing/publishing process may become more and more popular. In none other than the New York Times Book Review, Neal Pollack recently declared his intention to self-publish his next book using Kickstarter to generate his fixed costs and “an advance,” and last week bestseller Paulo Coelho discussed his decision to offer his novels for free online. (You can find free ebooks by Coelho here.)

Indeed, now more than ever, it seems essential for authors to meet readers at least half-way. Harwood considers himself an “author-preneur,” developing new business models as he publishes his books. As he sees it, innovation comes much more easily to an author acting alone, than to a large publishing company or big corporation. He aims for the new models as he sees them developing, knowing he’s got to go out and find readers himself. As Coelho declares, “The ivory tower does not exist anymore.”

This post was contributed by Shawna Yang Ryan. Her novel Water Ghosts was a finalist for the 2010 Asian American Literary Award. In 2012, she will be the Distinguished Writer in Residence at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

The Mechanical Monsters: Seminal Superman Animated Film from 1941

In 1941, director Dave Fleischer and Paramount Pictures animators Steve Muffati and George Germanetti produced Superman: The Mechanical Monsters — a big-budget animated adaptation of the popular Superman comics of that period, in which a mad scientist unleashes robots to rob banks and loot museums, and Superman, naturally, saves the day. It was one of seventeen films that raised the bar for theatrical shorts and are even considered by some to have given rise to the entire Anime genre.

More than a mere treat of vintage animation, the film captures the era’s characteristic ambivalence in reconciling the need for progress with the fear of technology in a culture on the brink of incredible technological innovation. It was the dawn of the techno-paranoia that persisted through the 1970s, famously captured in the TV series Future Shock narrated by Orson Welles, and even through today. Take for example books like Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows and Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other.

Superman: The Mechanical Monsters is available for download on The Internet Archive, and Toonami Digital Arsenal has the complete series of all seventeen films. Find more vintage animation in Open Culture’s collection of Free Movies Online.

Maria Popova is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings, a curated inventory of cross-disciplinary interestingness. She writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and DesignObserver, and spends a great deal of time on Twitter.

It’s 5:46 A.M. and Paris Is Under Water

Thanks to the creative work of Olivier Campagne & Vivien Balzi, you can see Paris looking a little like Venice does in the winter — mercifully freed from crowds and often under water. For more great perspectives on Paris and Venice, don’t miss:

Le Flaneur: Time Lapse Video of Paris Without the People

George Harrison in the Spotlight: The Dick Cavett Show (1971)

This week, HBO will air George Harrison: Living in the Material World, a two-part documentary dedicated to The Beatles’ guitarist who long played in the shadow of John and Paul. While George slips back in the spotlight, we should highlight his vintage interview with Dick Cavett. Recorded 40 years ago (November 23, 1971), the conversation starts with light chit-chat, then (around the 5:30 mark) gets to some bigger questions — Did Yoko break up the band? Did the other Beatles hold him back musically? Why have drugs been so present in the rock ‘n roll world, and did The Beatles’ flirtation with LSD lead youngsters astray? And is there any relationship between drugs and the Indian music that so fascinated Harrison? It was a question better left to Ravi Shankar to answer, and that he did.

The rest of the interview continues here with Part 2 and Part 3. Also, that same year, Cavett interviewed John Lennon and Yoko Ono, and we have it right here.

Jacques Derrida Deconstructs American Attitudes

Jacques Derrida, the founder of Deconstruction, was something of an academic rock star during his day. He packed auditoriums whenever and wherever he spoke. Films were made about him. And a generation of academics churned out Derridean deconstructions of literary texts. All of this made Derrida’s star rise ever higher. But whether it did much good for Comp Lit, French and English programs across the US, that’s another story.

But we digress from the main point here. Our friendly French philosopher spent a fair amount of time teaching in the US and got acquainted with American attitudes. Sometimes, he says, we can be manipulative and utilitarian. What exactly do you mean Mr. Derrida? Can you please elaborate? Of course, he does above.

Note: If you aren’t quite clear on what deconstruction is all about, you can watch two lectures devoted to the subject (here and here) from Yale’s course on Literary Theory. Entitled “Introduction to Theory of Literature,” this course, taught by Paul Fry, is listed in the Literature section of our big collection of Free Online Courses.

H/T Biblioklept

Related Content:

Jacques Lacan Speaks; Zizek Provides Free Cliffs Notes

Download Free Courses from Famous Philosophers: From Bertrand Russell to Michel Foucault

Sartre, Heidegger, Nietzsche: Three Philosophers in Three Hours

Learn 40 Languages (including French) for Free

Italy’s Youngest Led Head

If you liked Friday’s post, Jimmy Page Tells the Story of Kashmir, then you’ll have a little fun with this. A shorter version with subtitles appears here.

For more moments of cultural precociousness, don’t miss 3 year old Samuel Chelpka reciting Billy Collins’ poem “Litany,” and 3 year old Jonathan channeling the spirit of Herbert von Karajan while conducting the 4th movement of Beethoven’s 5th. H/T @MatthiasRascher

Follow us on Twitter and Facebook, and we’ll keep pointing you to free cultural goodies daily…

Jimmy Page Tells the Story of “Kashmir”

One of the most original and distinctive songs Led Zeppelin ever recorded was the exotic, eight-and-a-half minute “Kashmir,” from the 1975 album Physical Graffiti. In this clip from Davis Guggenheim’s film It Might Get Loud (2009), Jimmy Page explains the origins of the song to fellow guitarists Jack White and The Edge. Then Page demonstrates it by picking up an old modified Danelectro 59DC Double Cutaway Standard guitar that he played the song with on some of Led Zeppelin’s tours. (Watch Kashmir live here.)

In 1973, Page had been experimenting with an alternative D modal, or DADGAD, tuning often used on stringed instruments in the Middle East, when he hit upon the hypnotic, rising and falling riff. The song came together over a period of a couple of years. John Bonham added his distinctive, overpowering drums during a two-man recording session with Page at Headley Grange. Singer Robert Plant wrote the lyrics while he and Page were driving through the Sahara Desert in Southern Morocco. (Neither Page nor Plant had ever visited Kashmir, in the Himalayas.) Bassist and keyboard player John Paul Jones added the string and horn arrangements the following year. In a 1995 radio interview with Australian journalist Richard Kingsmill, Plant recalled his experience with “Kashmir”:

It was an amazing piece of music to write to, and an incredible challenge for me. Because of the time signature, the whole deal of the song is…not grandiose, but powerful. It required some kind of epithet, or abstract lyrical setting about the whole idea of life being an adventure and being a series of illuminated moments. But everything is not what you see. It was quite a task, because I couldn’t sing it. It was like the song was bigger than me.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Led Zeppelin Plays One of Its Earliest Concerts (Danish TV, 1969)

Thirteen-Year-Old Jimmy Page Makes his BBC Television Debut in 1957

Hear Led Zeppelin’s Mind-Blowing First Recorded Concert Ever (1968)

What Earth Will Look Like 100 Million Years from Now

This is what you’d call efficient. In two minutes, we watch our planet take form. 600 million years of geological history whizzes by in a snap. Then we see what the next 100 million years may have in store for us. If you don’t have the patience to watch 700 million years unfold in 180 seconds (seriously?), then we’ll give you this spoiler: Coastal real estate is not a long-term buy…

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

How to Peel a Head of Garlic in Less Than 10 Seconds

Random? Yes. Handy? Double yes. The ultimate culinary lifehack from SAVEUR magazine’s Executive Food Editor, Todd Coleman…

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Steven Pinker on the History of Violence: A Happy Tale

In July, the Edge.org held its annual “Master Class” in Napa, California and brought together some influential thinkers to talk about “The Science of Human Nature.” The highlights included:

Princeton psychologist Daniel Kahneman on the marvels and the flaws of intuitive thinking; Harvard mathematical biologist Martin Nowak on the evolution of cooperation; Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker on the history of violence; UC-Santa Barbara evolutionary psychologist Leda Cosmides on the architecture of motivation; UC-Santa Barbara neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga on neuroscience and the law; and Princeton religious historian Elaine Pagels on The Book of Revelations.

The Edge.org has now started making videos from the class available online, including, this week, Steven Pinker’s talk on the history of violence. You can watch Pinker’s full 86 minute talk here (sorry, we couldn’t embed it on our site.) Or, if you want the quick gist of Pinker’s thinking, then watch the short clip above. In five minutes, Pinker tells you why violence is steadily trending down, and why some things are actually going right in our momentarily/monetarily troubled world.