According to Ruth Graham in Slate, Banned Books Week is a “crock,” an unnecessary public indulgence since “there is basically no such thing as a ‘banned book’ in the United States in 2015.” And though the awareness-raising week’s sponsor, the American Library Association, has shifted its focus to book censorship in classrooms, most of the challenges posed to books in schools are silly and easily dismissed. Yet, some other cases, like that of Persepolis—Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel memoir of her Iranian childhood during the revolution—are not. The book was pulled from Chicago Public School classrooms (but not from libraries) in 2013.

Even now, teachers who wish to use the book in classes must complete “supplemental training.” The ostensibly objectionable content in the book is no more graphic than that in most history textbooks, and it’s easy to make the case that Persepolis and other challenged memoirs and novels that offer perspectives from other countries, cultures, or political points of view have inherent educational value. One might be tempted to think that school officials pulled the book for other reasons. Perhaps we need Banned Books Week after all.

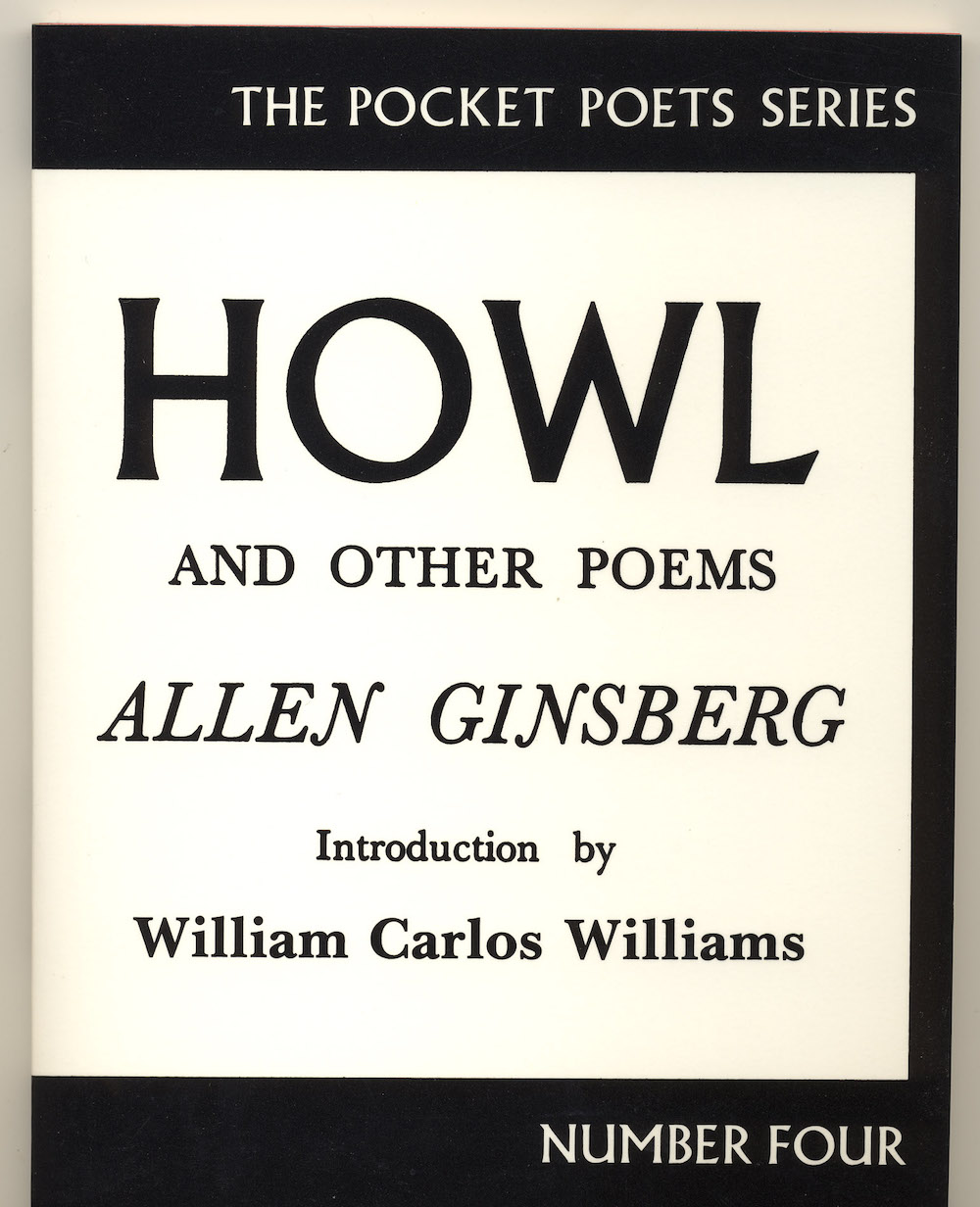

Another, perhaps fuzzier, case of a “banned” book—or poem—from this year involves a high school teacher’s firing over his classroom reading of Allen Ginsberg’s pornographic poem “Please Master.” The case of “Please Master” should put us in mind of a once banned book written by Ginsberg: epic Beat jeremiad “Howl.” When the poem’s publisher, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, attempted to import British copies of the poem in 1957, the books were seized by customs, then he and his business partner were arrested and put on trial for obscenity. After writers and academics testified to the poem’s cultural value, the judge vindicated Ferlinghetti, and “Howl.”

But the trial demonstrated at the time that the government reserved the right to seize books, stop their publication and sale, and keep material from the reading public if it so chose. As with this year’s dust-up over “Please Master,” the agents who confiscated “Howl” supposedly objected to the sexual content of Ginsberg’s poem (and likely the homosexual content especially). But that reasoning could also have been cover for other objections to the poem’s political content. “Howl,” after all, was very subversive in its day, and in a way served as a kind of manifesto against the status quo. It had a “cataclysmic impact,” writes Fred Kaplan, “not just on the literary world but on the broader society and culture.”

We’ve featured various readings of “Howl” in the past, and if you’ve somehow missed hearing those, never heard the poem read at all, or never read the poem yourself, then consider during this Banned Books Week taking the time to read it and hear it read—by the poet himself. You can hear the first recorded reading by Ginsberg, in 1956 at Portland’s Reed College. You can hear another impassioned Ginsberg reading from 1959. And above, hear Ginsberg read the poem in 1956, in San Francisco, where it was first published and where it stood trial.

You can also hear Ginsberg fan James Franco—who played the poet in a film called Howl—read the poem over a visually striking animation of its vivid imagery. And if Ginsberg isn’t your thing, consider checking out the ALA’s list of challenged or banned books for 2014–2015. (I could certainly recommend Persepolis.) While prohibiting books from the classroom may seem a far cry from government censorship, Banned Books Week reminds us that many people still find certain kinds of books deeply threatening, and should push us to ask why that is.

Related Content:

High School Teacher Reads Allen Ginsberg’s Explicit Poem “Please Master” and Loses His Job

The First Recording of Allen Ginsberg Reading “Howl” (1956)

Allen Ginsberg Reads His Famously Censored Beat Poem, Howl (1959)

James Franco Reads a Dreamily Animated Version of Allen Ginsberg’s Epic Poem ‘Howl’

Find great poems in our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness