Every year for the past decade or so, we‘ve seen new, dire pronouncements of the death of print, along with new, upbeat rejoinders. This year is no different, though the prognosis has seemed especially positive of late in robust appraisals of the situation from entities as divergent as The Onion’s A.V. Club and financial giant Deloitte. I, for one, find this encouraging. And yet, even if all printed media were in decline, it would still be the case that the history of the modern world will mostly be told in the history of print. And ironically, it is online media that has most enabled the means to make that history available to everyone, in digital archives that won’t age or burn down.

One such archive, the British Library’s Flickr Commons project, contains over one million images from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. As the Library wrote in their announcement of these images’ release, they cover “a startling mix of subjects. There are maps, geological diagrams, beautiful illustrations, comical satire, illuminated and decorative letters, colourful illustrations, landscapes, wall-paintings and so much more that even we are not aware of.” Microsoft digitized the books represented here, and then donated them to the Library for release into the Public Domain.

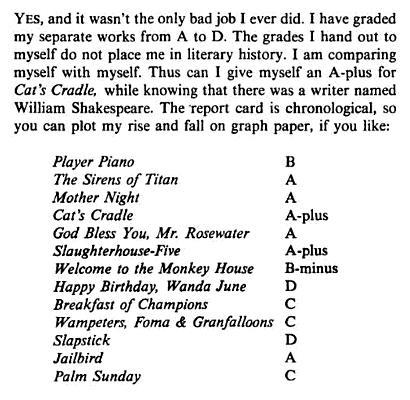

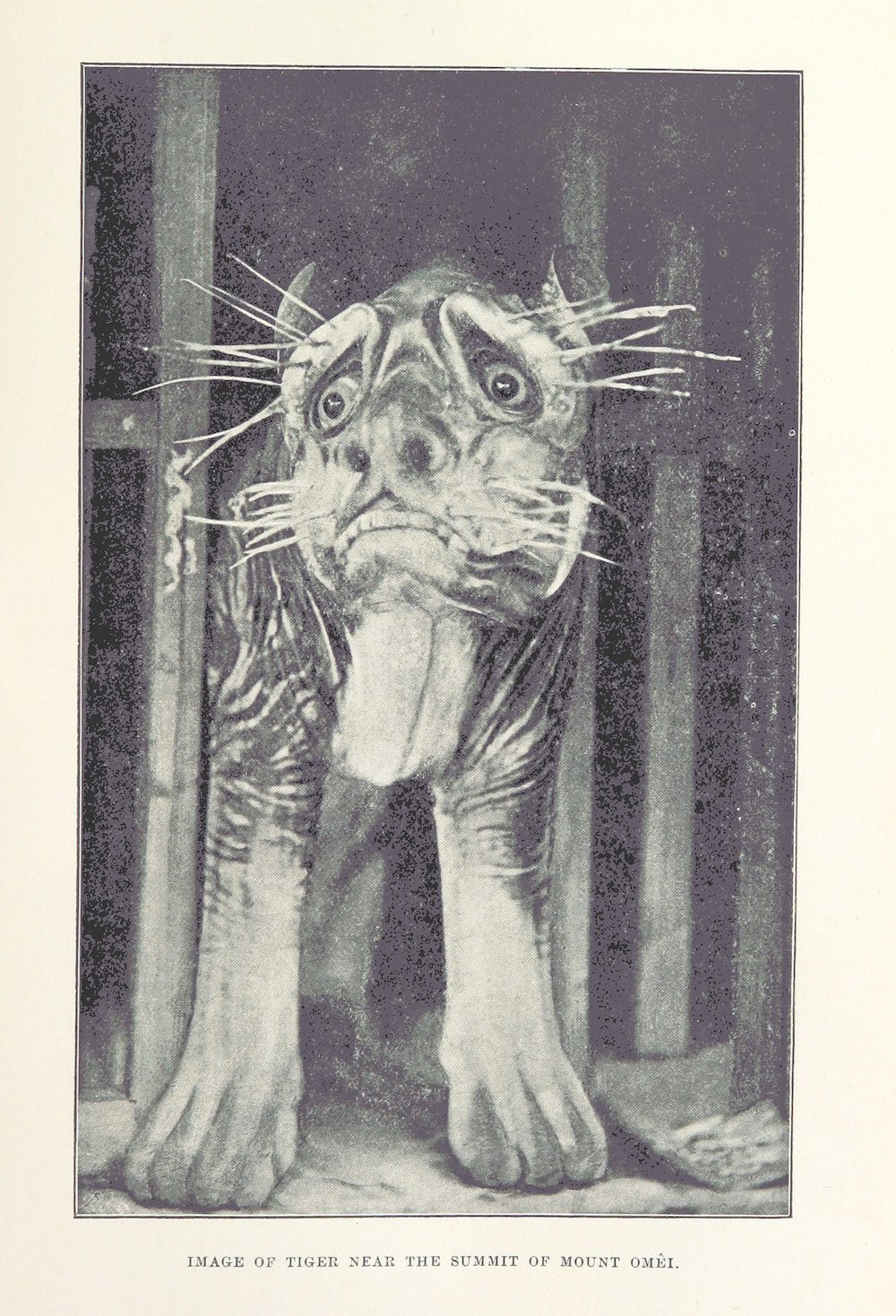

One of the quirky features of this decidedly quirky assemblage is the Mechanical Curator, a bot-run blog that generates “randomly selected small illustrations and ornamentations, posted on the hour.” At the time of writing, it has given us an ad for the rather culturally dated artifact “Oriental Tooth Paste,” a product “prepared by Jewsbury & Brown.” Many of the other selections have considerably less frisson. Nonetheless, writes the Library, often “our newest colleague,” the Mechanical Curator, “plucks from obscurity, places all before you, and leaves you to work out the rest. Or not.”

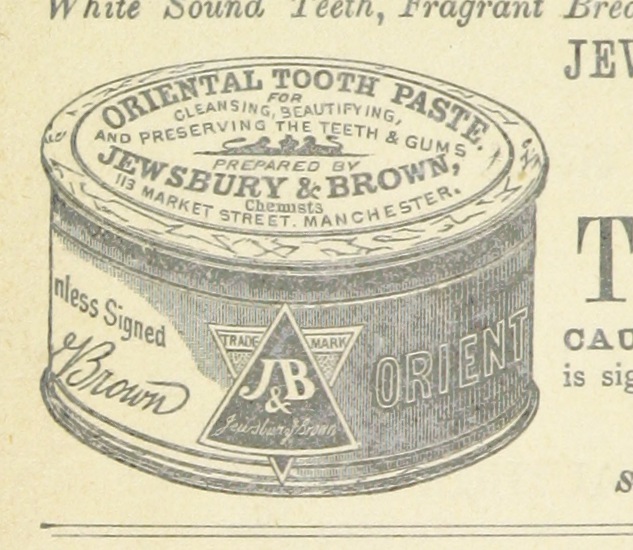

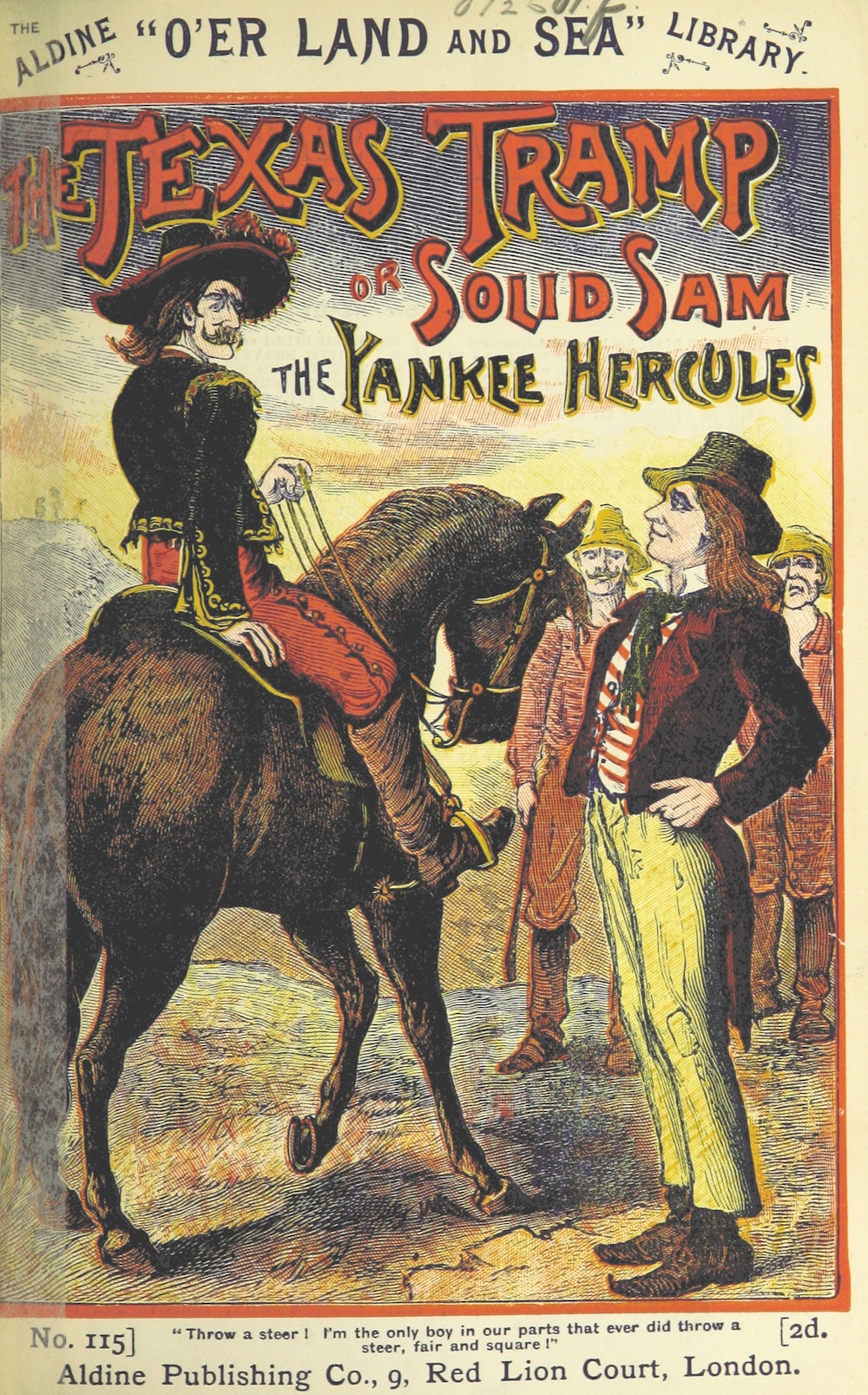

The Flickr Commons site itself gives us a much more conventional organization, with images—most of them discovered by the Mechanical Curator—grouped into several dozen themed albums. We have “Book covers found by the community from the Mechanical Curator Collection,” featuring images like that of The Texas Tramp or Solid Sam the Yankee Hercules, a pulpy title published in 1890 by the Aldine Library’s “O’er Land and Sea” series. And just above, see an illustration from the 1892 publication To the Snows of Tibet through China…With Illustrations and a Map. Each image’s page offers links to other illustrations in the book and those of other books published in the same year.

Here, we have a striking illustration from an 1841 edition of The Cottager’s Sabbath, a poem… with … vignettes… by H. Warren. This image comes from “Architecture, found by the community from the Mechanical Curator Collection.”

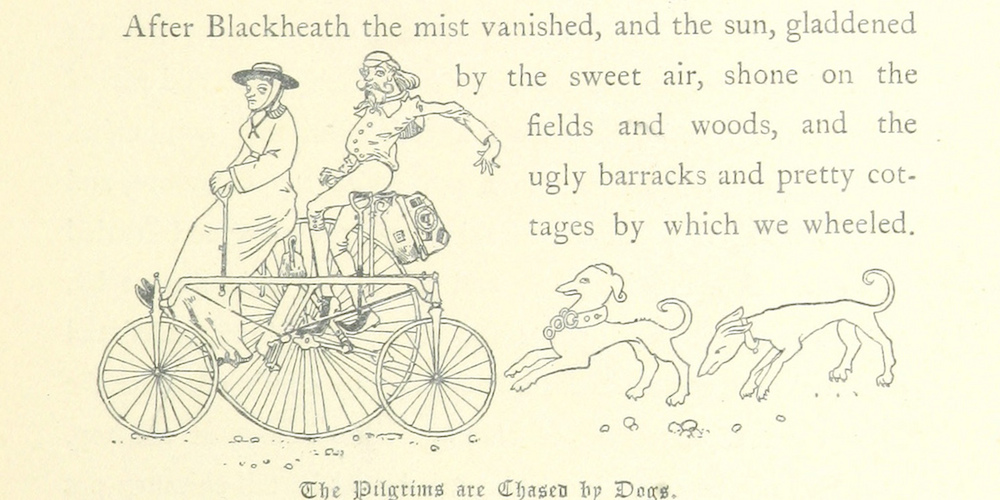

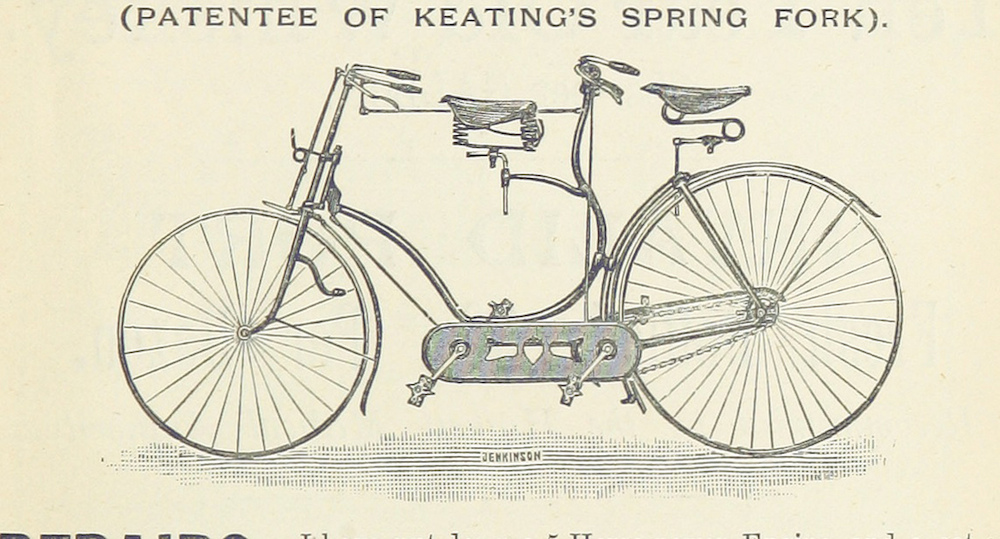

We also have oddities like the illustration above, from 1885’s “A Canterbury Pilgrimage, ridden, written, and illustrated by J. and E.R.P.” This is to be found in “Cycling, found by the community from [you guessed it] the Mechanical Curator Collection,” which also contains plenty of more commercial illustrations like the 1893 “Patentee of Keating’s Spring Fork.”

Speaking of commerce, we also have an album devoted to advertisements, found by the community from, yes, the Mechanical Curator Collection. Here you will discover ads like “Oriental Tooth Paste” or that below for “Gentlemen’s & Boy’s Clothing 25 Per Cent. Under Usual London Prices” from 1894. Our conception of Victorian England as excessively formal gets confirmed again and again in these ads, which, like the random choice at the top of the post, contain their share of awkward or humorous historical notions.

Doubtless none of the proto-Mad Men of these very English publications foresaw such a marvel as the Mechanical Curator. Much less might they have foreseen such a mechanism arising without a monetizing scheme. But thanks to this free, newfangled algorithm’s efforts, and much assistance from “the community,” we have a digital record that shows us how public discourse shaped print culture, or the other way around. A fascinating, and at times bewildering, feature of this phenomenal archive is the requirement that we ourselves supply most of the cultural context for these austerely presented images.

Related Content:

2,200 Radical Political Posters Digitized: A New Archive

Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Download for Free 2.6 Million Images from Books Published Over Last 500 Years on Flickr

Download 100,000 Free Art Images in High-Resolution from The Getty

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness