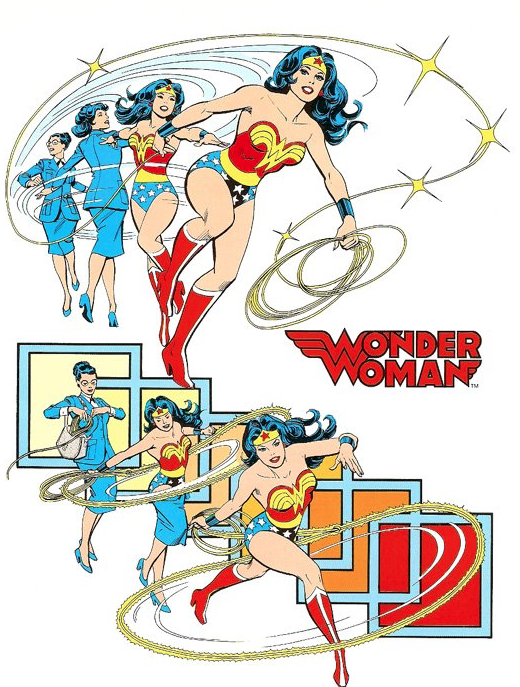

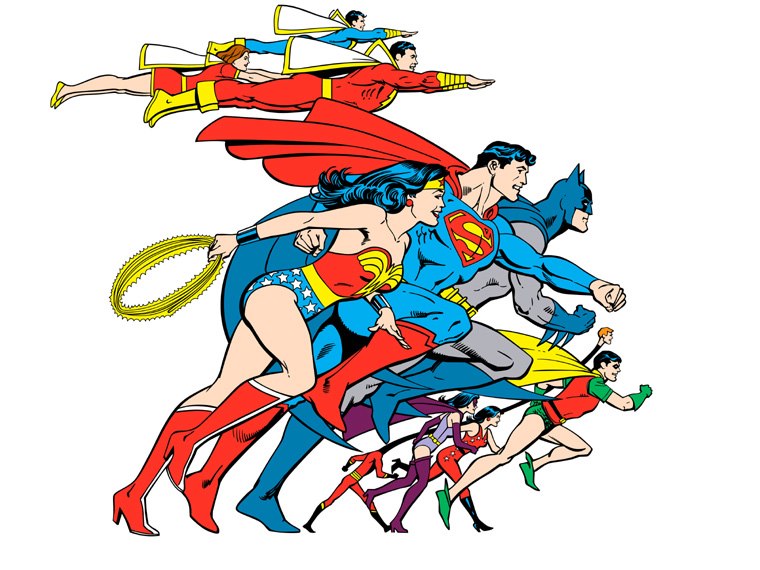

Even if you don’t like comic books, think of names like Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, and you get a very clear mental picture indeed. Classic superheroes live, breathe, battle supervillians, and even die and return to life across decades upon decades of storylines (and often more than one at once), but we all know them because, just like the most enduring corporate logos, they also stand as surpassingly effective works of commercial art. But given that countless different artists in various media have had to render these superheroes over those decades, how have their images remained so utterly consistent?

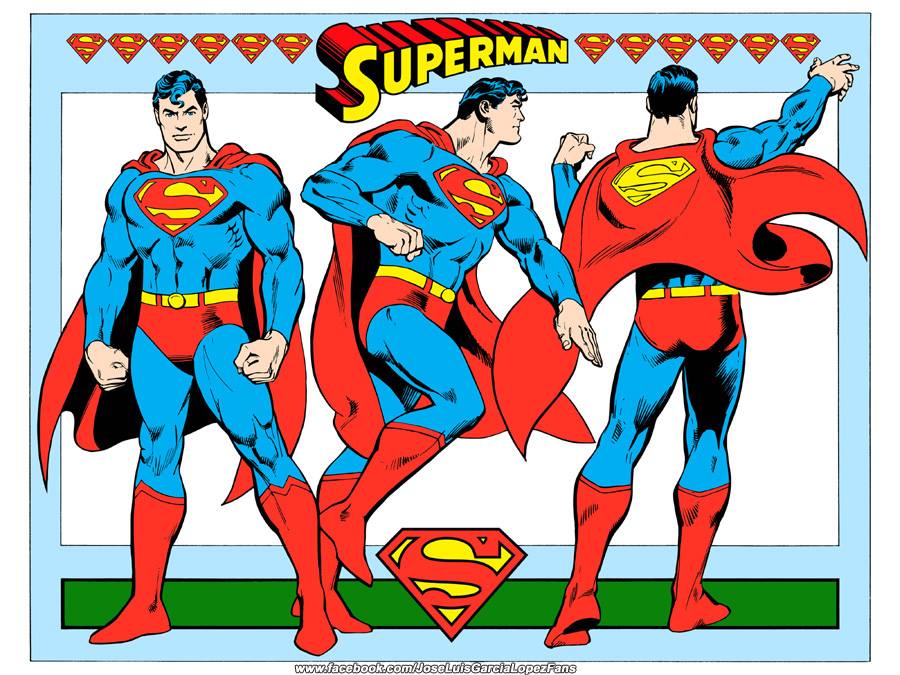

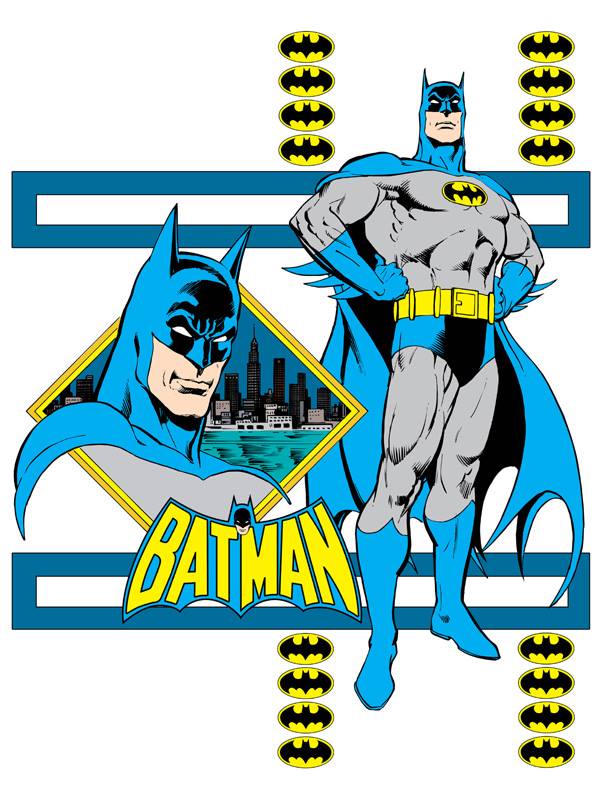

That owes to documents such as the 1982 DC Comics Style Guide, scanned and recently posted to a Facebook group for fans of comic-book artist José Luis García-López. Having spent most of his career with DC Comics, caretaker of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and many other well-known and much-licensed heroes and villains besides, García-López surely knows in his very bones the sort of details of costume, physique, posture, and bearing these style guides exist to convey.

Being 33 years old, this particular style guide doesn’t perfectly reflect the way all of DC’s superheroes look today, what with the aesthetic changes made to keep them hip year on year. But you’ll notice that, while fashions tend to have their way with the more minor characters (longtime DC fans especially lament the headband and big hair this style guide inflicted upon Supergirl), the major ones still look, on the whole, pretty much the same. Sure, Superman has the strength and the flight, Batman has the wealth and the vast armory of high-tech crime-fighting tools, and Wonder Woman can do pretty much anything, but all those abilities pale in comparison to the sheer power of their design. You can flip through the rest of the Style Guide here.

(via Metafilter)

Related Content:

Download Over 22,000 Golden & Silver Age Comic Books from the Comic Book PlusArchive

Download 15,000+ Free Golden Age Comics from the Digital Comic Museum

Kapow! Stan Lee Is Co-Teaching a Free Comic Book MOOC, and You Can Enroll for Free

Batman & Other Super Friends Sit for 17th Century Flemish Style Portraits

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.