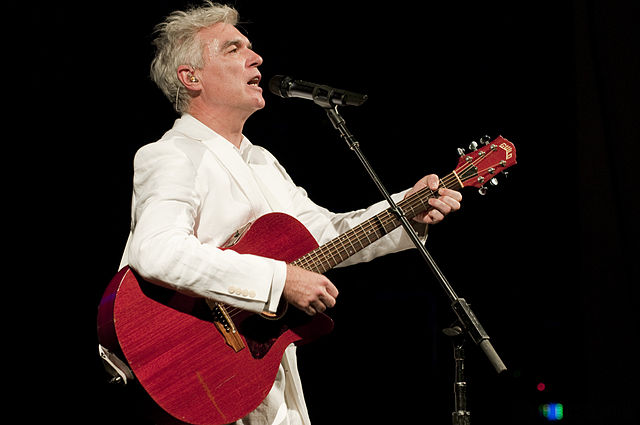

Photo courtesy of LivePict.com CC-BY-SA‑3.0.

David Byrne has played many roles: frontman of Talking Heads, architectural observer, composer of opera (specifically opera about Imelda Marcos, former first lady of the Philippines, the country from which I write this post today), enthusiastic musical collaborator, urban cycling advocate — and that only counts the ones he’s played here in Open Culture posts. (Someday, we’ve got to write up his love of Powerpoint.) But did you know he’s also done a free internet radio show, and for nearly a decade at that? “For one or two days a month I queue up David Byrne’s Radio Station on the web and listen to his two-hour loop of new, wonderful, delicious tunes,” writes Kevin Kelly in a Cool Tools post from 2008, just over halfway into the life of the show so far. “Rock-star Byrne is a professional musical pioneer, admirably eclectic in his taste, yet astutely discriminating at the same time. Over years of listening to all kinds of music — experimental, indie, international, fringe, classical, pop — he’s heard enough to make some great recommendations.”

Kelly cites such tantalizing Byrnean playlists as “Icelandic Pop,” “Opera highlights,” “Eclectic Stuff,” and “African Fusion Pop.” More recent sessions, which can run for three hours or longer, include “Southern Writers,” “Songs of Burt Bacharach,” and “Raga Rock.” A new playlist comes out every month. You can list to his August playlist, “Custom Jackets, Now and Then,” a celebration of women “who have been tainted or touched by country music” including Neko Case, Emmylou Harris, Gillian Welch, and Lucinda Williams. You can also hear a brand new November playlist on the davidbyrne.com front page, which uses a newer audio player than all the previous installments. “Viva Mexico Part 1” promises a selection of artists from that vibrant country who “have found ways to incorporate their Mexican musical heritage and culture into what might be called the global pop form,” resulting not in “imitations of North American or UK alt-rock” but songs that “sound like nothing but themselves.” And if you can’t trust David Byrne to know musical uniqueness when he hears it, who can you trust?

Related Content:

David Byrne: How Architecture Helped Music Evolve

David Byrne: From Talking Heads Frontman to Leading Urban Cyclist

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.