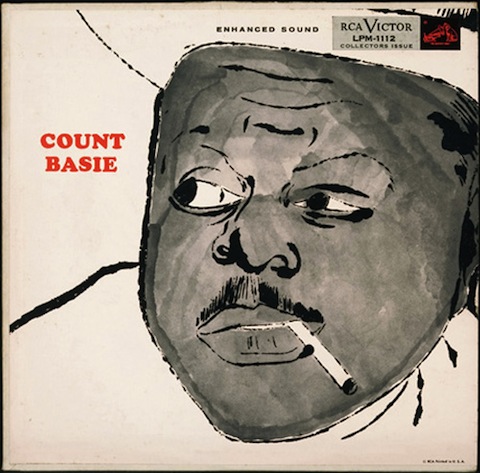

Flavorwire titles their post on album covers designed by artist Andy Warhol—auteur of that special brand of late-midcentury, impassive yet rocking-and-rolling, New York-rooted American cool—“Beyond the Banana.” They refer, of course, to the fruit emblazoned upon The Velvet Underground & Nico, the 1967 debut album from the avant-rock band formed right there in Warhol’s own “Factory.” It would, of course, insult your cultural awareness to post an image of that particular cover and ask if you knew Andy Warhol designed it. But how about that of Count Basie’s self-titled 1955 album above? Warhol, not a figure most of us associate immediately with jazz and its traditions, designed it, too.

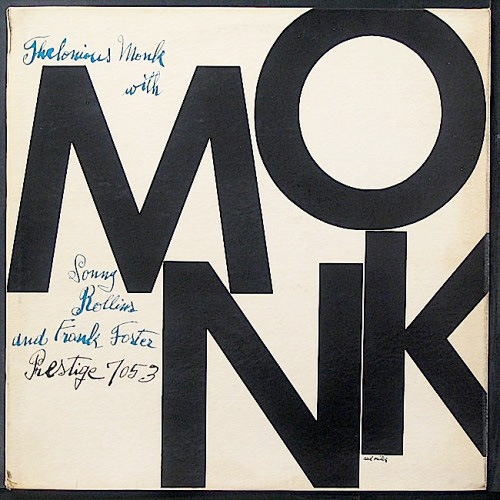

He also did one for 1954’s MONK: Thelonious Monk with Sonny Rollins and Frank Foster, and, in 1958, for guitarist Kenny Burrell’s Blue Note double-disc Blue Lights.

We now regard Blue Note highly for its taste in not only the aesthetics of the music itself but also the packaging that surrounds it, and thus we might assume the label had a natural inclination to work with a visionary like Warhol. But in the late fifties, Blue Lights stretched Blue Note’s graphical sensibilities as well as Warhol’s own; with it, he “finally broke away from simply drawing close-ups of musicians and their instruments and delivered a piece of art as evocative as the music inside,” writes the San Francisco Chronicle’s Aidin Vaziri.

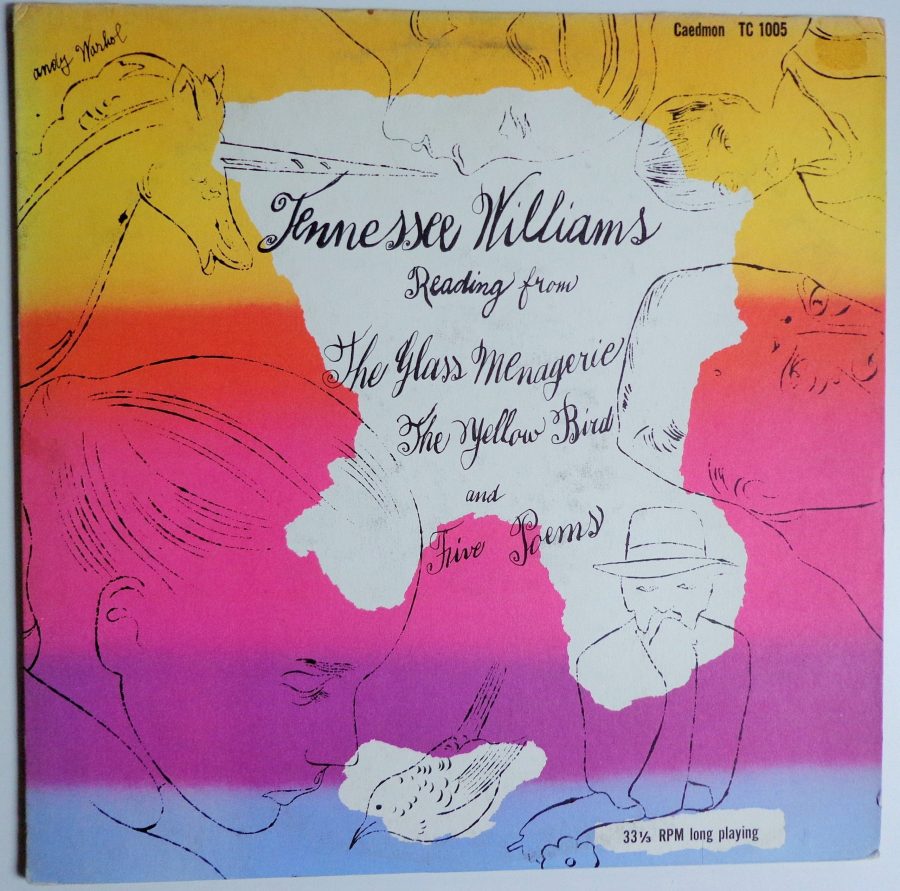

Given Warhol’s interest in the United States and its icons, it stands to reason that he would take on design jobs for Basie, Monk, and Burrell just as readily as he would for the Velvet Underground, or for those Englishmen who could out-American the Americans, the Rolling Stones. He even did an album cover for a representative of a whole other slice of American culture: playwright Tennesee Williams, author of plays like The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

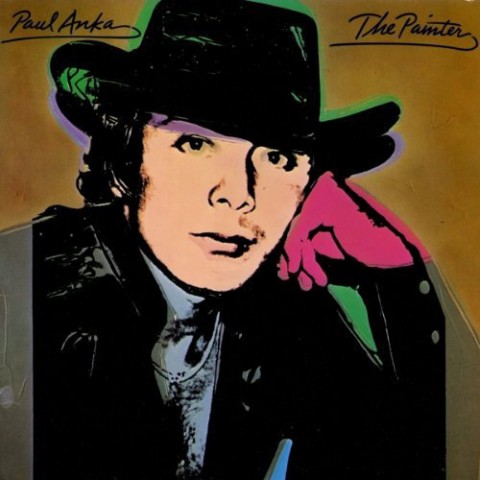

In 1952, Caedmon put out a record called Tennessee Williams Reading from The Glass Menagerie, The Yellow Bird and Five Poems, and its 1960 printing bears the Warhol artwork you see just above. Warhol in all these shows an impressive willingness to adapt to the persona of the musician and the feel of their music; a casual Warhol enthusiast may own one of these albums for years without ever realizing who did the cover art. He didn’t even cleave exclusively toward American forms, or to styles that mainstream America might once have considered artistically edgy. You could hardly get further from the position of the Velvet Underground than easy-listening vocals, let alone the easy-listening vocals of the Canadian-born Paul Anka, but when the singer’s 1976 The Painter needed a cover, Warhol delivered — and with a recognizably Warholian look, no less.

Warhol’s album covers, from 1949 to 1987, have been collected in the book, Andy Warhol: The Complete Commissioned Record Covers.

See more Warhol album covers at NME, SFGate, and Flavorwire.

Related Content:

Bob Egan, Detective Extraordinaire, Finds the Real Locations of Iconic Album Covers

Classic Jazz Album Covers Animated, or the Re-Birth of Cool

Record Cover Art by Underground Cartoonist Robert Crumb

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.