Image by Moody Man, via Flickr Commons

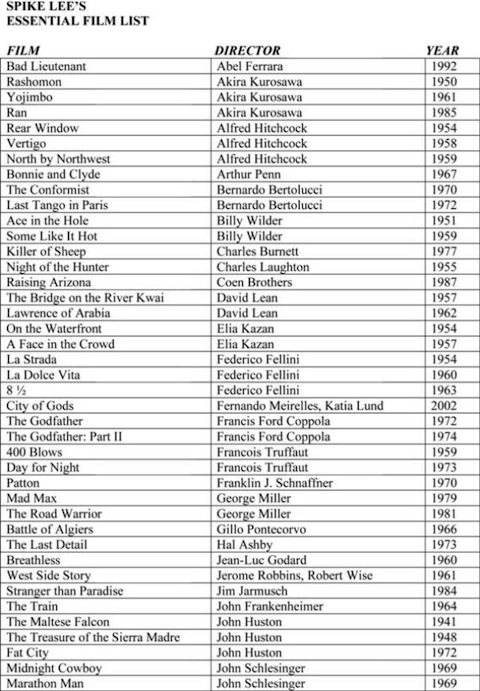

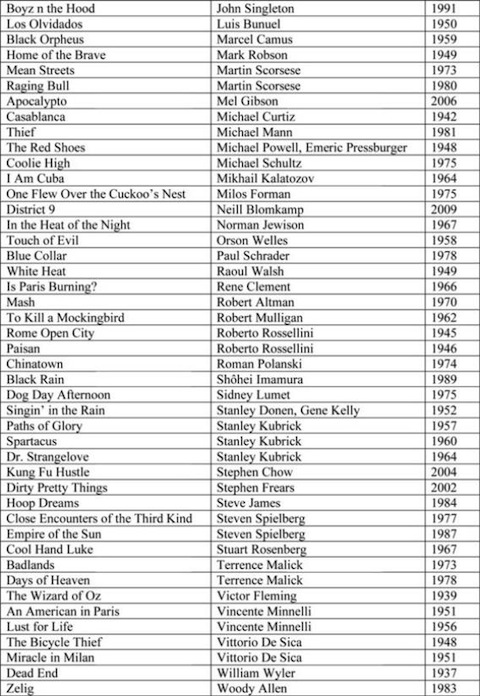

When, over the past weekend, I noticed the words “Stanley Kubrick” had risen into Twitter’s trending-topics list, I got excited. I figured someone had discovered, in the back of a long-neglected studio vault, the last extant print of a Kubrick masterpiece we’d somehow all forgotten. No suck luck, of course; Kubrick scholars, given how much they still talk about even the auteur’s never-realized projects like Napoleon, surely wouldn’t let an entire movie slip into obscurity. The burst of tweets actually came in honor of Kubrick’s 85th birthday, and hey, any chance to celebrate a director whose filmography includes the likes of Dr. Strangelove, The Shining, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, I’ll seize. The British Film Institute marked the occasion by posting a little-seen list of Kubrick’s top ten films.

“The first and only (as far as we know) Top 10 list Kubrick submitted to anyone was in 1963 to a fledgling American magazine named Cinema (which had been founded the previous year and ceased publication in 1976),” writes the BFI’s Nick Wrigley. It runs as follows:

1. I Vitelloni (Fellini, 1953)

2. Wild Strawberries (Bergman, 1957)

3. Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941)

4. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (Huston, 1948)

5. City Lights (Chaplin, 1931)

6. Henry V (Olivier, 1944)

7. La notte (Antonioni, 1961)

8. The Bank Dick (Fields, 1940—above)

9. Roxie Hart (Wellman, 1942)

10. Hell’s Angels (Hughes, 1930)

But seeing as Kubrick still had 36 years to live and watch movies after making the list, it naturally provides something less than the final word on his preferences. Wrigley quotes Kubrick confidant Jan Harlan as saying that “Stanley would have seriously revised this 1963 list in later years, though Wild Strawberries, Citizen Kane and City Lights would remain, but he liked Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V much better than the old and old-fashioned Olivier version.” He also quotes Kubrick himself as calling Max Ophuls the “highest of all” and “possessed of every possible quality,” calling Elia Kazan “without question the best director we have in America,” and praising heartily David Lean, Vittorio de Sica, and François Truffaut. This all comes in handy for true cinephiles, who can never find satisfaction watching only the filmmakers they admire; they must also watch the filmmakers the filmmakers they admire admire.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Stanley Kubrick’s Very First Films: Three Short Documentaries

Terry Gilliam: The Difference Between Kubrick (Great Filmmaker) and Spielberg (Less So)

Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Stanley Kubrick Never Made

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.