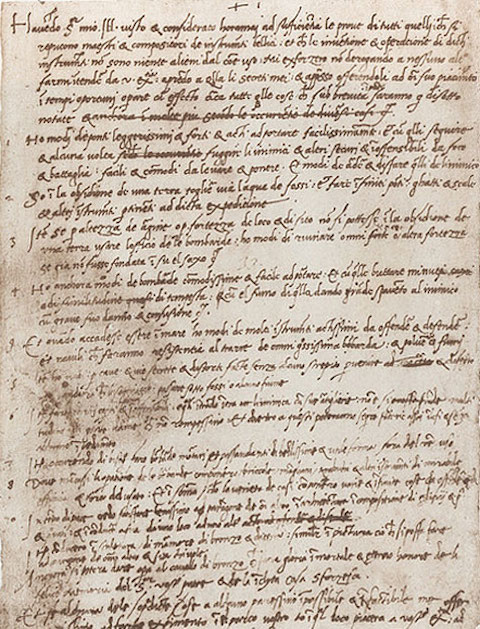

We know that Michelangelo wrote grocery lists; now we have evidence that Leonardo wrote resumes. “Before he was famous, before he painted the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper, before he invented the helicopter, before he drew the most famous image of man, before he was all of these things, Leonardo da Vinci was an artificer, an armorer, a maker of things that go ‘boom,’ ” writes Marc Cendella on his blog about job-searching and recruitment advice. “Like you, he had to put together a resume to get his next gig. So in 1482, at the age of 30, he wrote out a letter and a list of his capabilities and sent it off to Ludovico il Moro, Duke of Milan.” Having yet to establish his reputation as perhaps the Italian Renaissance’s most respected polymath, Leonardo spelled himself out, in translation, as follows:

Most Illustrious Lord, Having now sufficiently considered the specimens of all those who proclaim themselves skilled contrivers of instruments of war, and that the invention and operation of the said instruments are nothing different from those in common use: I shall endeavor, without prejudice to any one else, to explain myself to your Excellency, showing your Lordship my secret, and then offering them to your best pleasure and approbation to work with effect at opportune moments on all those things which, in part, shall be briefly noted below.

1. I have a sort of extremely light and strong bridges, adapted to be most easily carried, and with them you may pursue, and at any time flee from the enemy; and others, secure and indestructible by fire and battle, easy and convenient to lift and place. Also methods of burning and destroying those of the enemy.

2. I know how, when a place is besieged, to take the water out of the trenches, and make endless variety of bridges, and covered ways and ladders, and other machines pertaining to such expeditions.

3. If, by reason of the height of the banks, or the strength of the place and its position, it is impossible, when besieging a place, to avail oneself of the plan of bombardment, I have methods for destroying every rock or other fortress, even if it were founded on a rock, etc.

4. Again, I have kinds of mortars; most convenient and easy to carry; and with these I can fling small stones almost resembling a storm; and with the smoke of these cause great terror to the enemy, to his great detriment and confusion.

5. And if the fight should be at sea I have kinds of many machines most efficient for offense and defense; and vessels which will resist the attack of the largest guns and powder and fumes.

6. I have means by secret and tortuous mines and ways, made without noise, to reach a designated spot, even if it were needed to pass under a trench or a river.

7. I will make covered chariots, safe and unattackable, which, entering among the enemy with their artillery, there is no body of men so great but they would break them. And behind these, infantry could follow quite unhurt and without any hindrance.

8. In case of need I will make big guns, mortars, and light ordnance of fine and useful forms, out of the common type.

9. Where the operation of bombardment might fail, I would contrive catapults, mangonels, trabocchi, and other machines of marvellous efficacy and not in common use. And in short, according to the variety of cases, I can contrive various and endless means of offense and defense.

10. In times of peace I believe I can give perfect satisfaction and to the equal of any other in architecture and the composition of buildings public and private; and in guiding water from one place to another.

11. I can carry out sculpture in marble, bronze, or clay, and also I can do in painting whatever may be done, as well as any other, be he who he may.

Again, the bronze horse may be taken in hand, which is to be to the immortal glory and eternal honor of the prince your father of happy memory, and of the illustrious house of Sforza.

And if any of the above-named things seem to anyone to be impossible or not feasible, I am most ready to make the experiment in your park, or in whatever place may please your Excellency – to whom I comment myself with the utmost humility, etc.

Even the densest fifteenth-century Duke, I wager, could see the use in a man able to make portable bridges, get water out of trenches, destroy rock built upon rock, fling a storm of stones, fortify vessels, pass under rivers, and make everything from “big guns,” catapults, mangonels, and trabocchi to unattackable covered chariots. Though Leonardo understandably concentrates on his wartime engineering skills, he also touches on the range of other disciplines — Renaissance man, remember — he has mastered, like architecture, sculpture, and painting. Perhaps most impressively of all, he rattles off all these points without seeming particularly boastful. “You’ll notice he doesn’t recite past achievements,” Cendella adds, “because those are about his achievements, and not about the Duke’s needs.” Still, he might have added that, given just a few more years, he could design a pretty captivating organ.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Michelangelo’s Handwritten 16th-Century Grocery List

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To-Do List from 1490: The Plan of a Renaissance Man