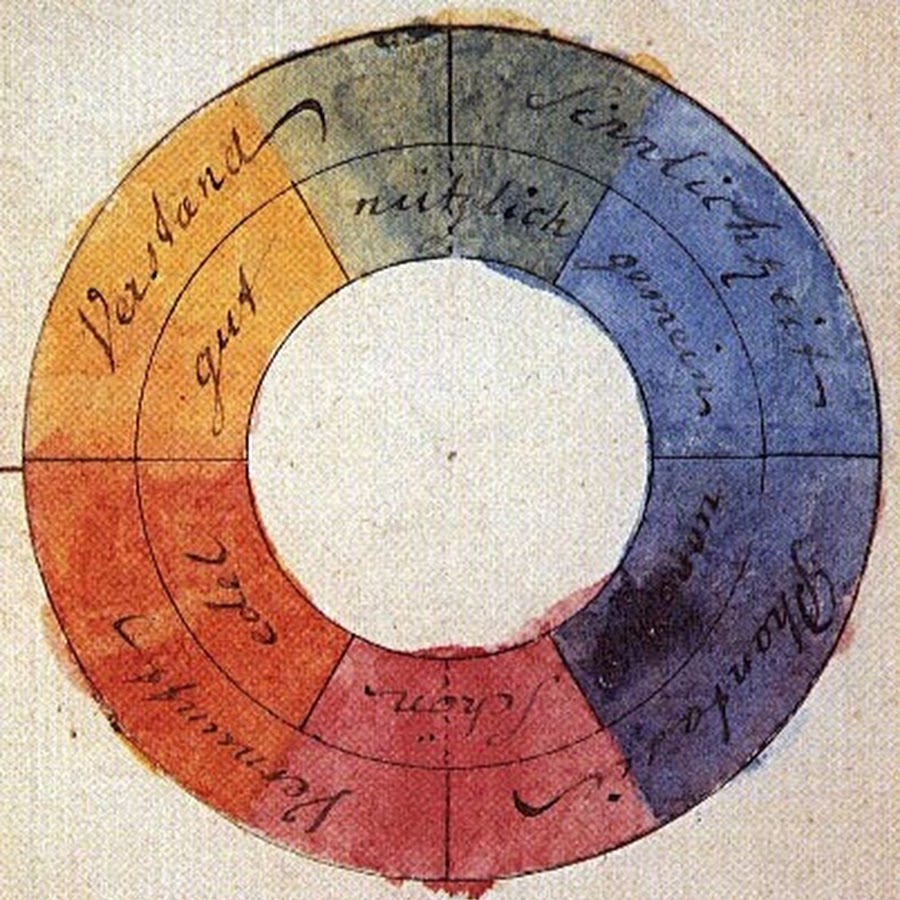

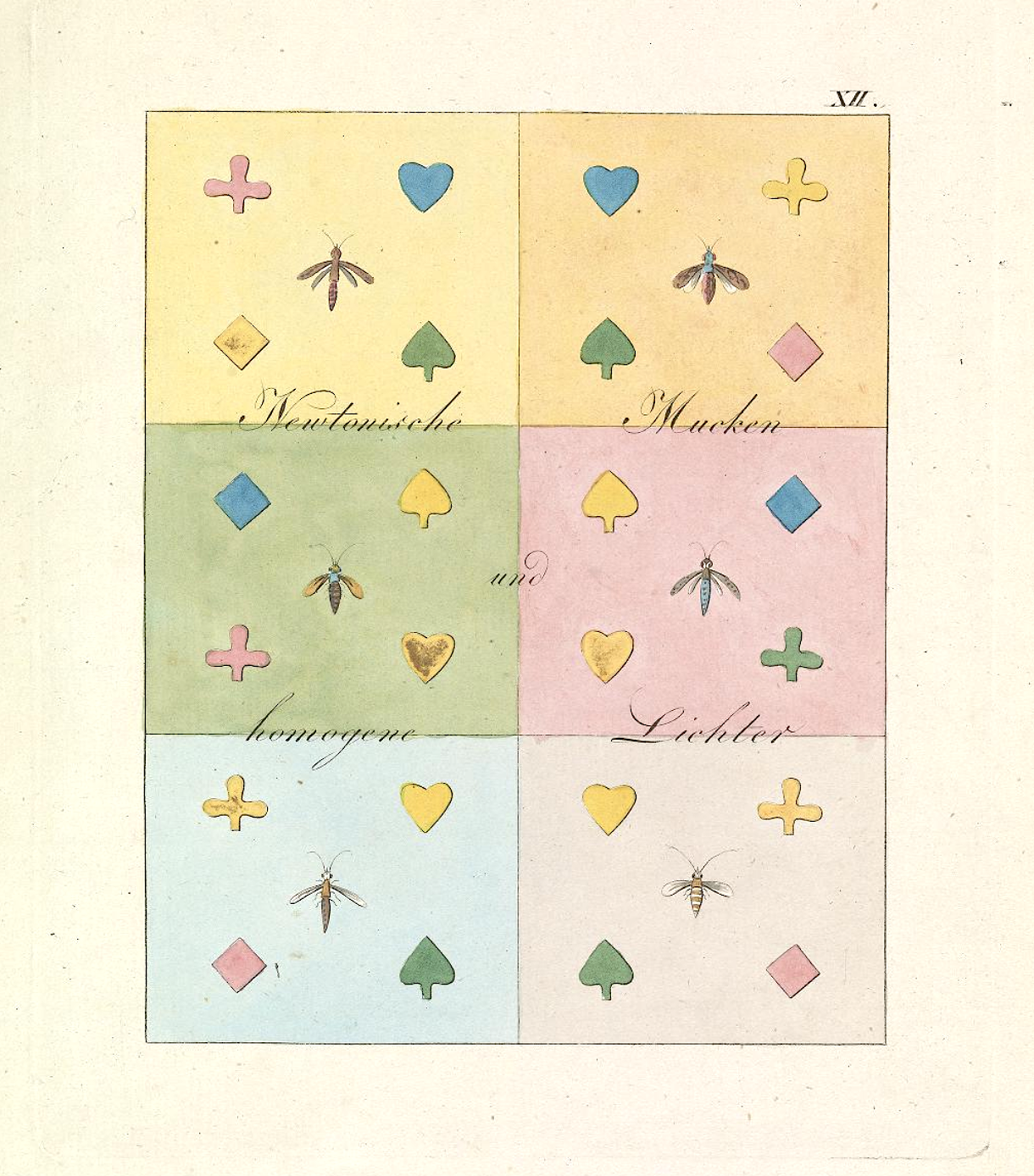

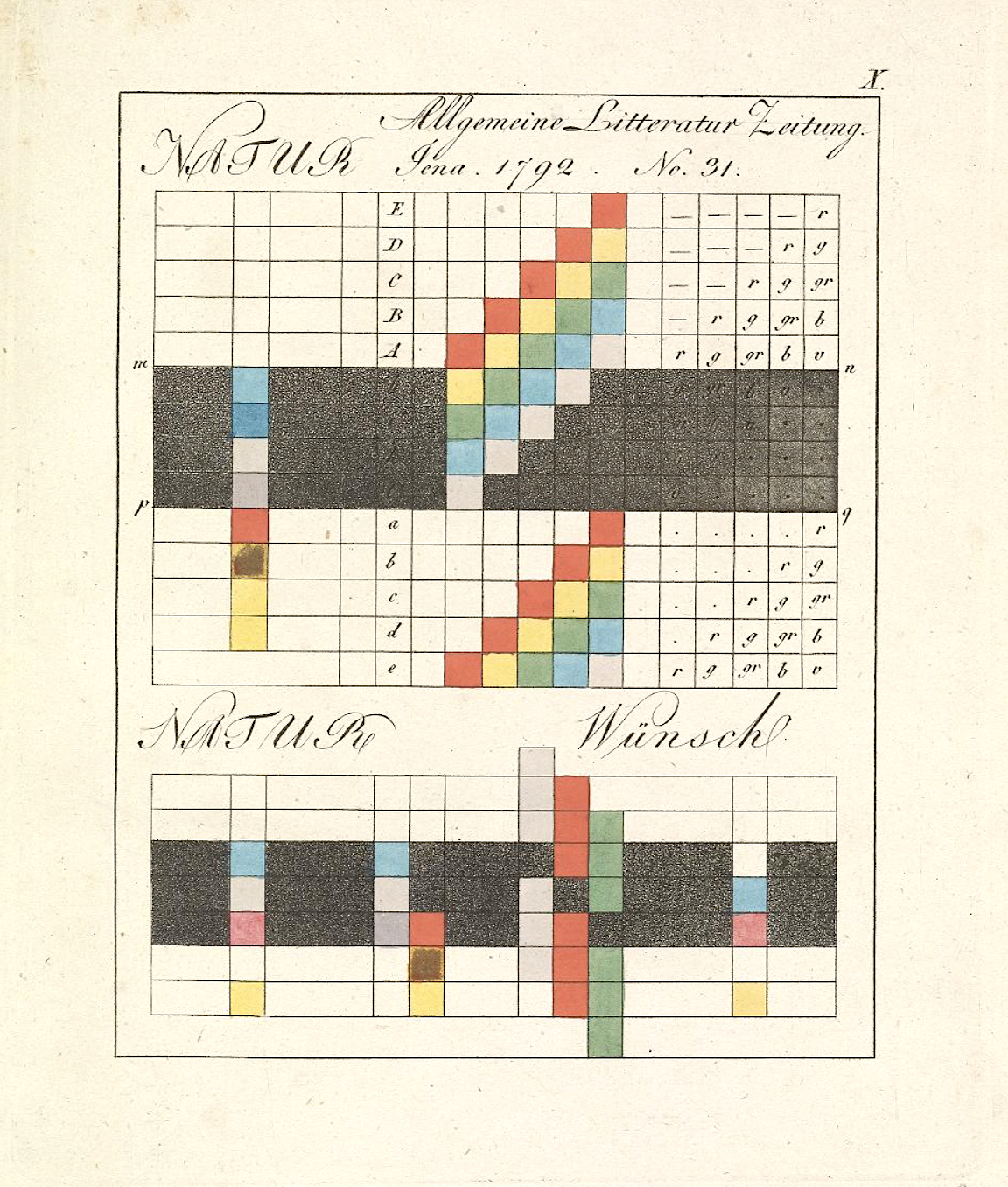

I doubt I need to list for you the many titles of the 18th century German savant and polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, but allow me to add one or two that were new to me, at least: color theorist (or phenomenologist of color) and progenitor of abstract expressionism. As a fascinating Booktryst post informs us, Goethe’s book on color, Zur Farbenlehre (Theory of Colors), written in 1810, disputed the Newtonian view of the subject and formulated a psychological and philosophical account of the way we actually experience color as a phenomenon. In his account, Goethe describes how he came by his views:

Along with the rest of the world, I was convinced that all the colors are contained in the light; no one had ever told me anything different, and I had never found the least cause to doubt it, because I had no further interest in the subject.

But how I was astonished, as I looked at a white wall through the prism, that it stayed white! That only where it came upon some darkened area, it showed some color, then at last, around the window sill all the colors shone… It didn’t take long before I knew here was something significant about color to be brought forth, and I spoke as through an instinct out loud, that the Newtonian teachings were false.

Schopenhauer would later write that “[Goethe] delivered in full measure what was promised by the title of his excellent work: data toward a theory of colour. They are important, complete, and significant data, rich material for a future theory of colour.” It was a theory, Schopenhauer admits, that does not “[furnish] us with a real explanation of the essential nature of colour, but really postulates it as a phenomenon, and merely tells us how it originates, not what it is.”

Another later philosophical interpreter of Goethe, Ludwig Wittgenstein—a thinker greatly interested in visual perception—also saw Goethe’s work as operating very differently than Newton’s optics—not as a scientific theory but rather as an intuitive schema. Wittgenstein remarked that Goethe’s work “is really not a theory at all. Nothing can be predicted by means of it. It is, rather, a vague schematic outline, of the sort we find in [William] James’s psychology. There is no experimentum crucis for Goethe’s theory of colour.”

Yet a third later German genius, Werner Heisenberg, commented on the influence of Zur Farbenlehre, writing that “Goethe’s colour theory has in many ways borne fruit in art, physiology and aesthetics. But victory, and hence influence on the research of the following century, has been Newton’s.”

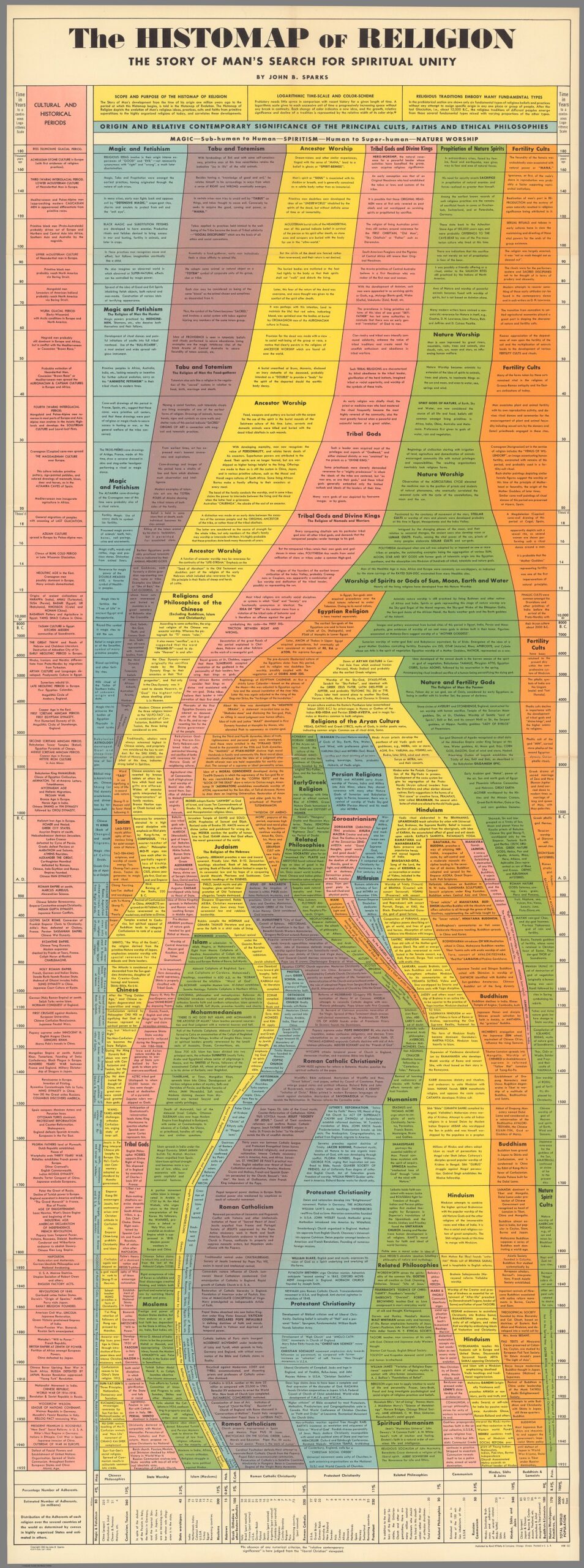

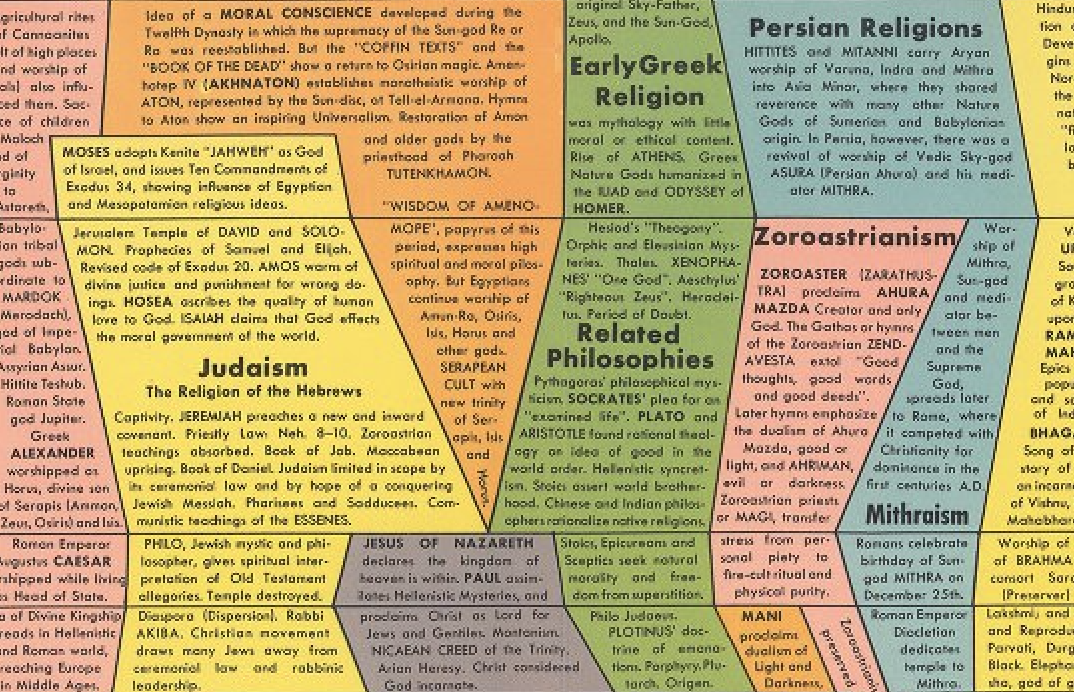

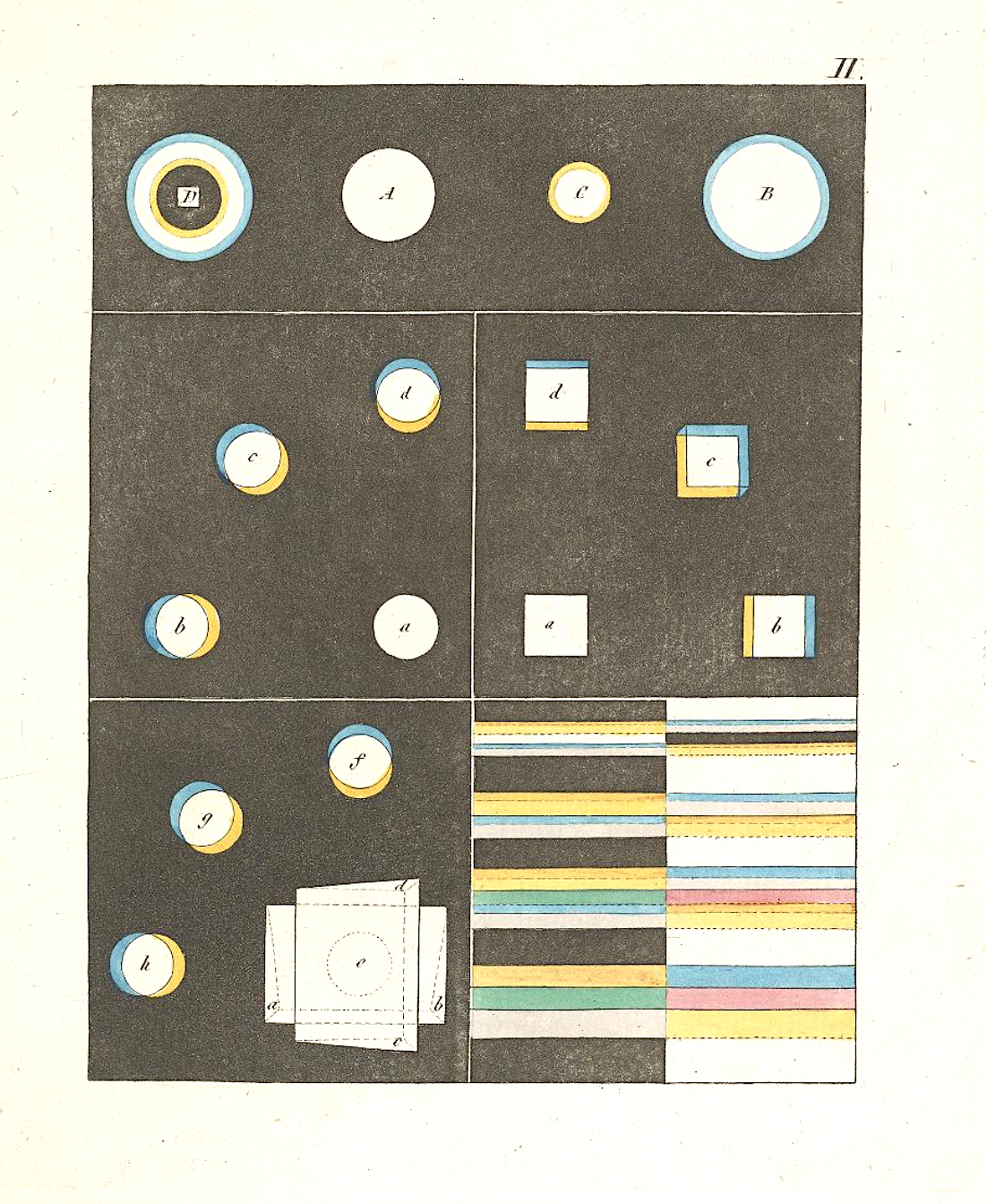

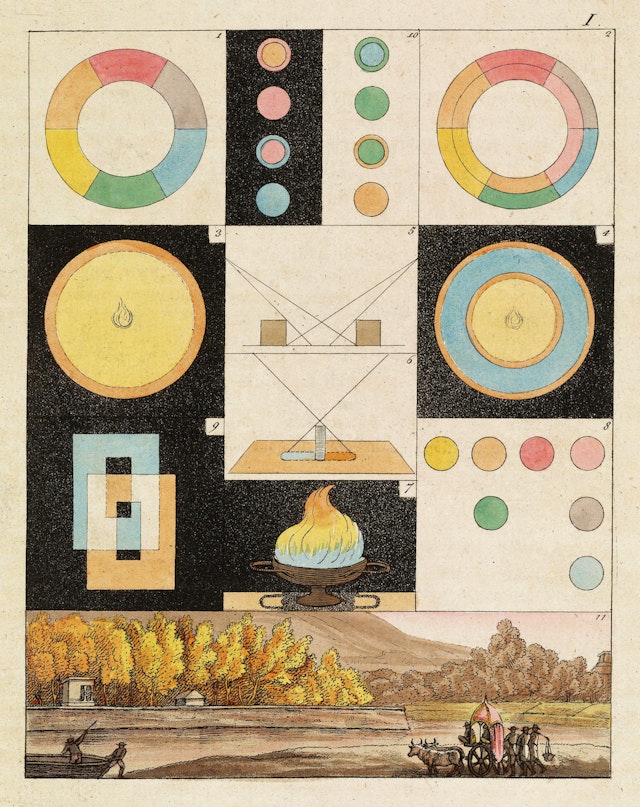

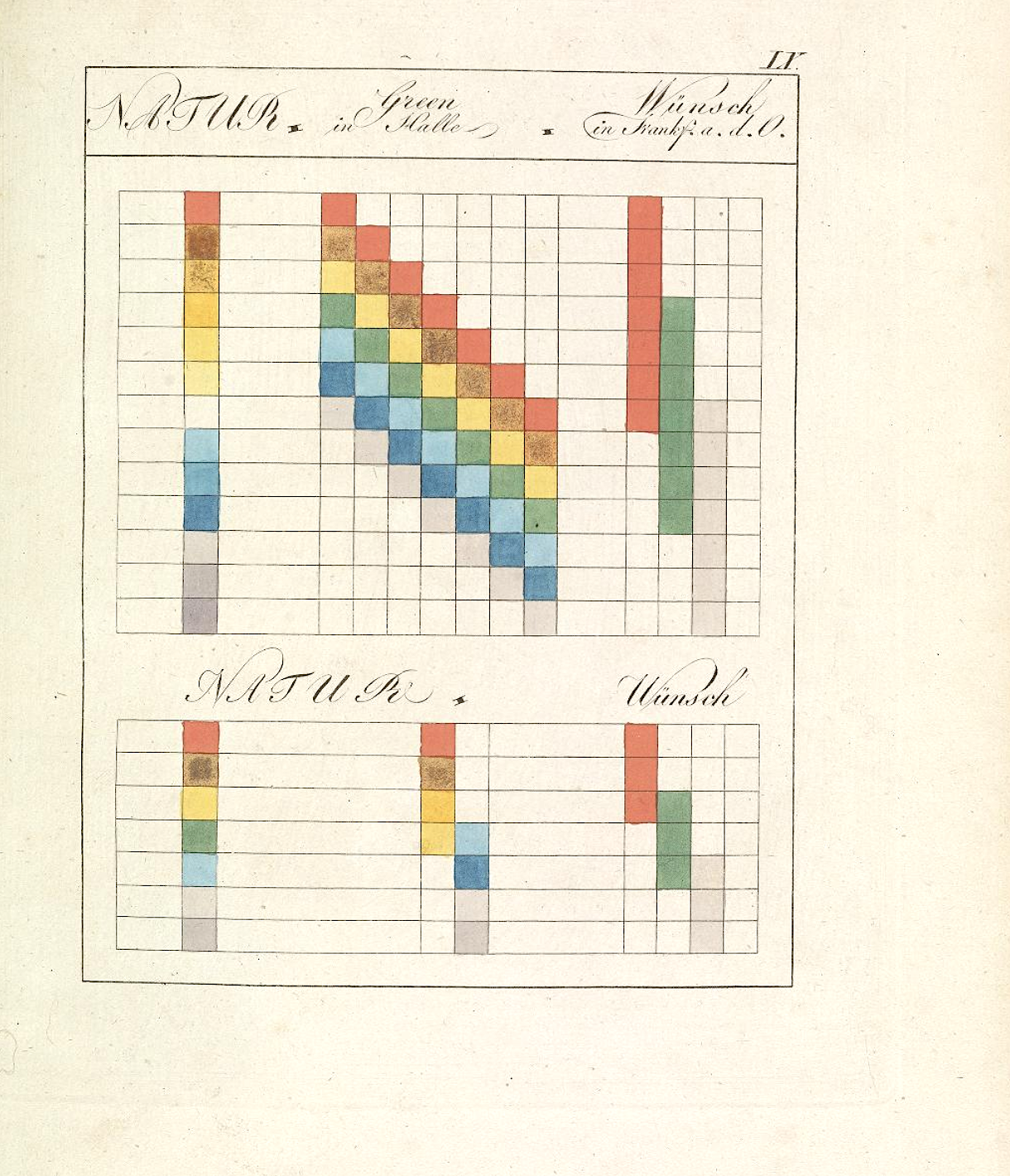

I’m not fit to evaluate the relative merits of Goethe’s theory, or lack thereof, versus Newton’s rigorous work on optics. Whole books have been written on the subject. But whatever his intentions, Goethe’s work has been well-received as a psychologically accurate account that has also, through his text and many illustrations you see here, had significant influence on twentieth century painters also greatly concerned with the psychology of color, most notably Wassily Kandinsky, who produced his own “schematic outline” of the psychological effects of color titled Concerning the Spiritual in Art, a classic of modernist aesthetic theory. As is usually the case with Goethe, the influence of this single work is wider and deeper than he probably ever foresaw.

You can find an affordable version of Goethe’s Theory of Colors on Amazon. Or find scans of the book at Archive.org.

Note: This post originally appeared on our site in 2013. We have updated the post with new images and links.

Related Content:

A 900-Page Pre-Pantone Guide to Color from 1692: A Complete Digital Scan

An Animated Introduction to Goethe, Germany’s “Renaissance Man”

Harry Clarke’s 1926 Illustrations of Goethe’s Faust: Art That Inspired the Psychedelic 60s

Watch Goethe’s Haunting Poem, “Der Erlkönig,” Presented in an Artful Sand Animation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness