Image by Rizka, via Wikimedia Commons

In South Korea, where I live, there may be no brand as respected as Habodeu. Children dream of it; adults seemingly do anything to play up their own connections to it, however tenuous those connections may be. But what is Habodeu? An electronics company? A line of clothing? Some kind of luxury car? Not at all: it is, in fact, the Korean pronunciation of Harvard, the American university. Practically everyone around the world is aware of Harvard’s prestige, but relatively few know that you can take many of its courses online without paying tuition, or even applying. In fact, you can find a list of more than 130 such courses right here, all available to take right now.

Those looking to start building a base of technical skill might consider Introduction to Computer Science or Introduction to Programming (of which there’s even a version for lawyers). Once you’ve got a handle on coding, you could move on to other courses in data science or machine learning and artificial intelligence.

If your scientific interests lie elsewhere, Harvard also has such online offerings as Fundamentals of Neuroscience, The Einstein Revolution, and Science & Cooking for both physics and chemistry. If you’d prefer to shore up your knowledge of religion, there are also courses on Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Sikhism through their scriptures.

Faith in art can also be satisfied through, to name just a few examples, Masterpieces of World Literature (with specialized courses in masterpieces modern and ancient); the life and work of Shakespeare and such specific plays as Hamlet, The Merchant of Venice, and Othello; pieces of music including Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring; and courses on Japanese books and Chinese humanities. But then, since we happen to live in what the Chinese call “interesting times,” perhaps you feel a more urgent need to take courses on American government and its constitutional foundations, civic engagement, the modern media environment, and resilient leadership. You can even take the blockbuster course on justice from the political philosopher Michael Sandel: a huge celebrity here in Korea, incidentally, even by Habodeu standards. Find the complete list of free online courses here. Also see our list, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related content

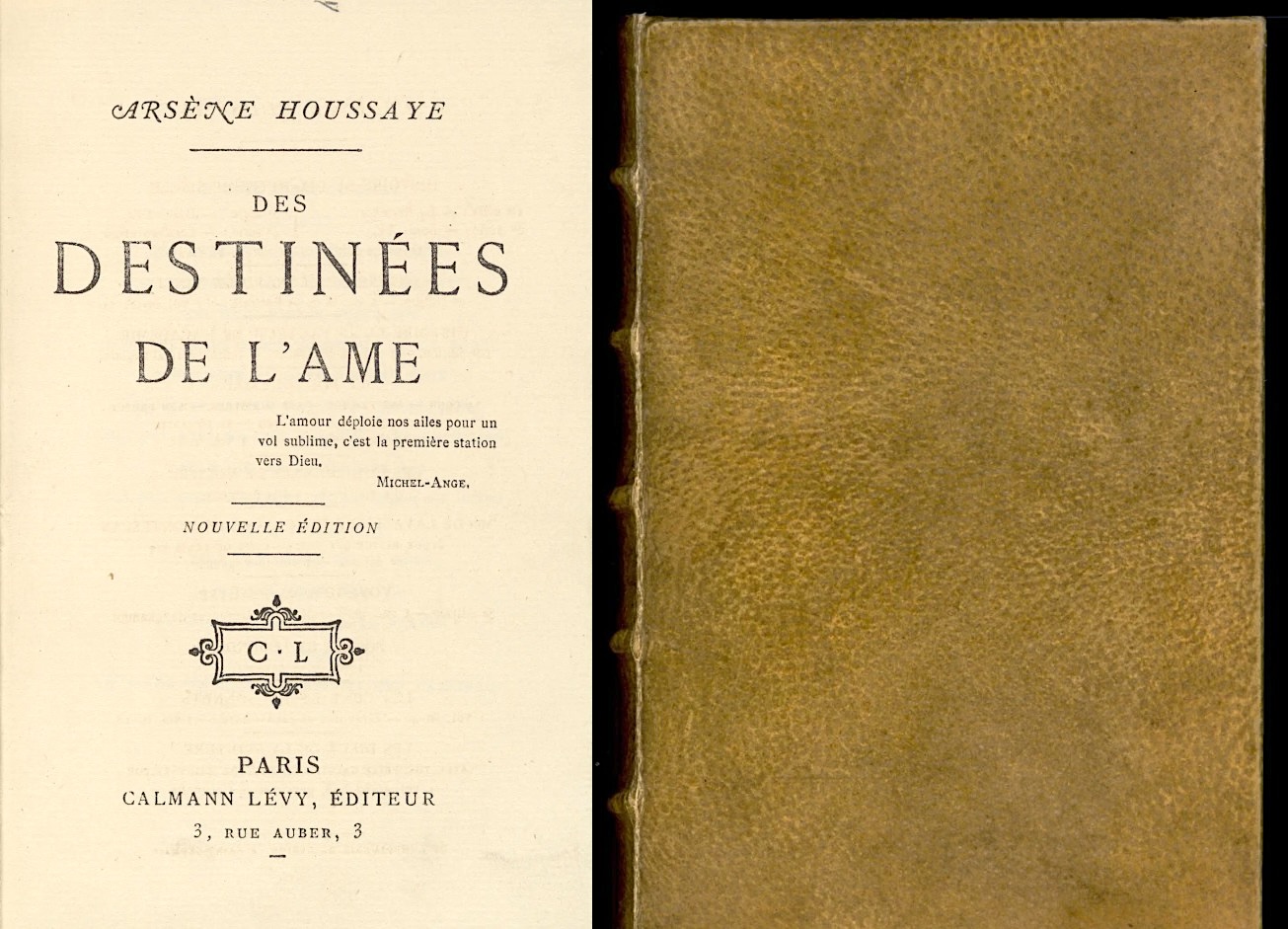

Download The Harvard Classics as Free eBooks: A “Portable University” Created in 1909

An Animated Michael Sandel Explains How Meritocracy Degrades Our Democracy

Harvard Puts Online a Huge Collection of Bauhaus Art Objects

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.