Chances are, if you can define the word phenomenology, you’re already a student of the 20th century philosophical school, field, movement, or—as its earliest expositor, Edmund Husserl wrote in a preface to the English edition of his 1913 Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology, “new science—though, indeed, the whole course of philosophical development since Descartes has been preparing the way for it.”

Husserl’s messianic claim for phenomenological thinking–that which, broadly, deals with the contents of consciousness and the objects of experience–presages the discipline’s enormity, well represented by the totalizing thought of Martin Heidegger, the Nazi philosopher who intended with his 1927 Being and Time to accomplish the “destruction” of philosophy. In a way, writes Simon Critchley, he succeeded. “There is no way of understanding what took place in continental philosophy after Heidegger without coming to terms with Being and Time.”

Another prominent phenomenologist, French thinker Maurice Merleau-Ponty, asserts a no less mind-bogglingly huge mandate for the method: “phenomenology is the study of essences,” he writes in his 1947 Phenomenology of Perception. “It is the search for a philosophy which shall be a ‘rigorous science,’ but it also offers an account of space, time and the world as we ‘live’ them.” Again, if this makes sense to you, you may already be a student of phenomenology, and you’ve probably read a lot of it.

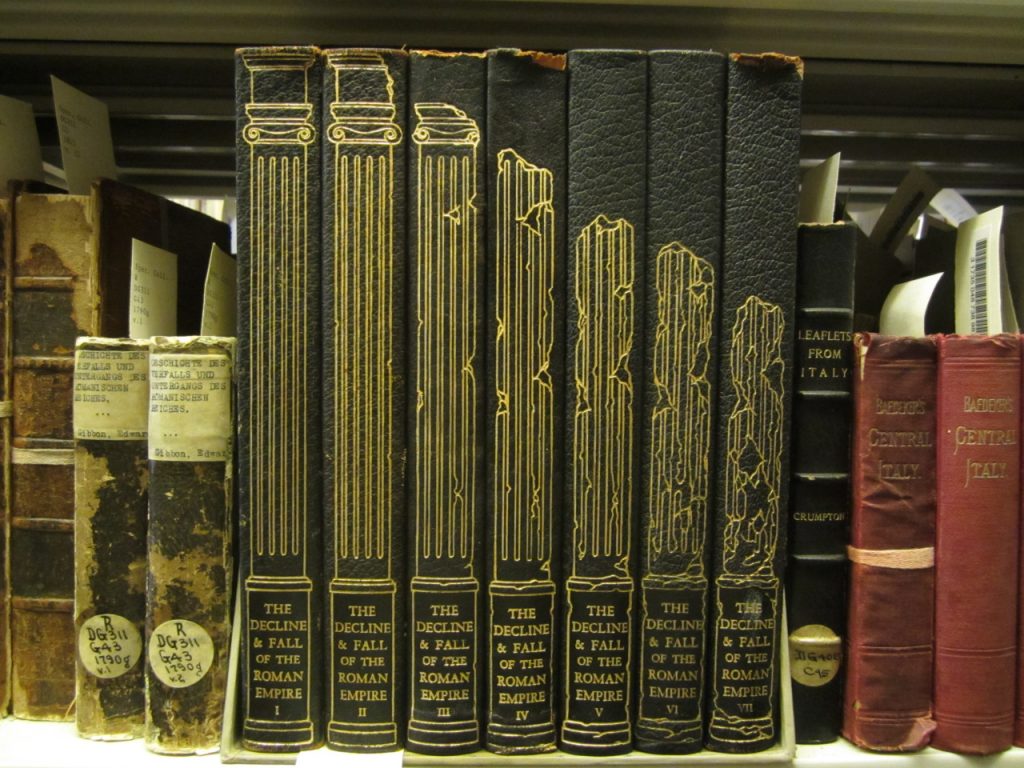

Philosophy students and professors must have ready access to a huge number of texts by a wide range of authors, most of whom are having multiple conversations with each other at once. It is, of course, ideal to have at hand the kinds of resources one might find at the Stadtbibliothek in Berlin, one of the largest libraries in the world, or even at most large university libraries. But if you don’t have such access, you can still gather a fair number of full texts by Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty and their many famous students and colleagues on the web.

Soon, you will be able to do so all in one place, in multiple languages and formats, at the Open Commons of Phenomenology, a “non-profit, international scholarly association” aiming to “provide free access to the full corpus of phenomenology” by 2020. A suitably ambitious task for a very ambitious school of thought. Currently, project founders Patrick Flack (whom you’ll see in the promo video at the top), Rodney Parker, Nicolas de Warren, and the Husserl Archives have compiled “about 12000 bibliographic entries,” close to a quarter of which link to open access pdfs.

The project still needs to iron out a number kinks, and broken links, but it plans in the coming years to collect not only previously online essays and books, but also newly digitized texts and translations, “enhanced with a number of powerful tools, such as interactive timelines and genealogies of phenomenologists and psychologists, .xml versions of texts,” and much more. Read more about the project at Daily Nous, at the now-closed Indiegogo page from its funding campaign last year, and at the Open Commons site itself, where you’ll also find reviews, calls for papers, lists of events, and more. The dense outline on the site’s About page promises great things for this new “digital infrastructure” of phenomenology research. Enter the Open Commons of Phenomenology here.

via Daily Nous

Related Content:

Take First-Class Philosophy Courses Anywhere with Free Oxford Podcasts

Free Online Philosophy Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness