Painter Diego Rivera set the bar awfully high for other lovers when he—allegedly—ate a handful of his ex-wife Frida Kahlo’s cremains, fresh from the oven.

Perhaps he was hedging his bets. The Mexican government opted not to honor his express wish that their ashes should be co-mingled upon his death. Kahlo’s remains were placed in Mexico City’s Rotunda of Illustrious Men, and have since been transferred to their home, now the Museo Frida Kahlo.

Rivera lies in the Panteón Civil de Dolores.

Other creative expressions of the grief that dogged him til his own death, three years later:

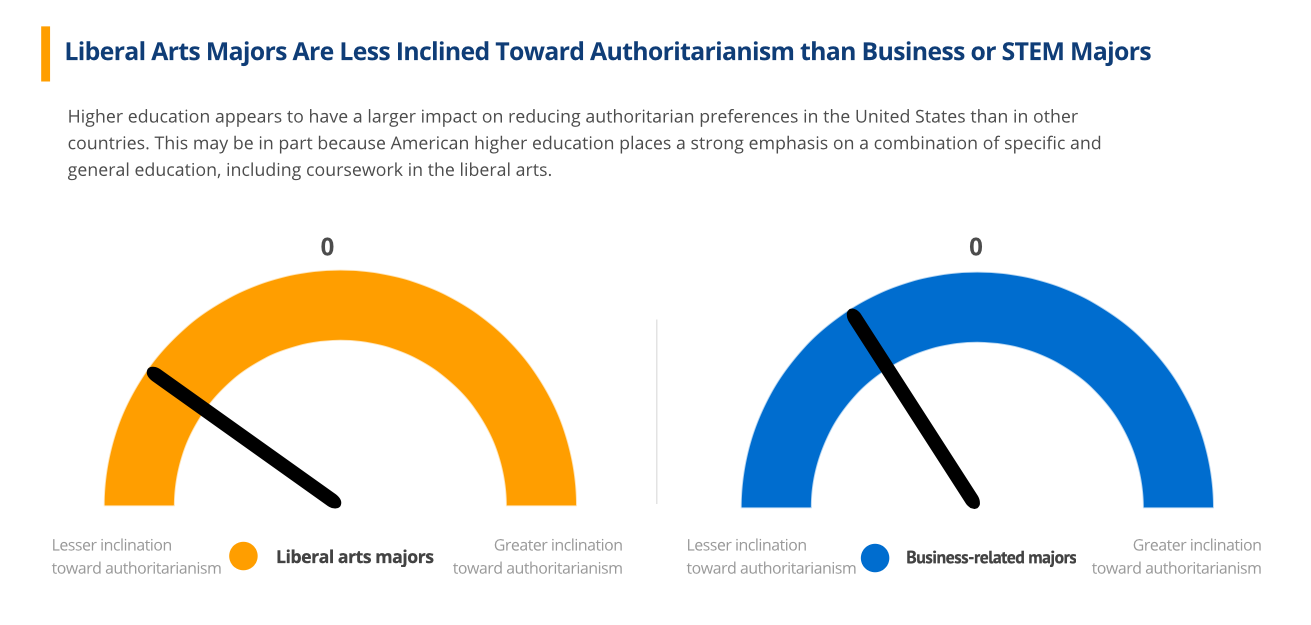

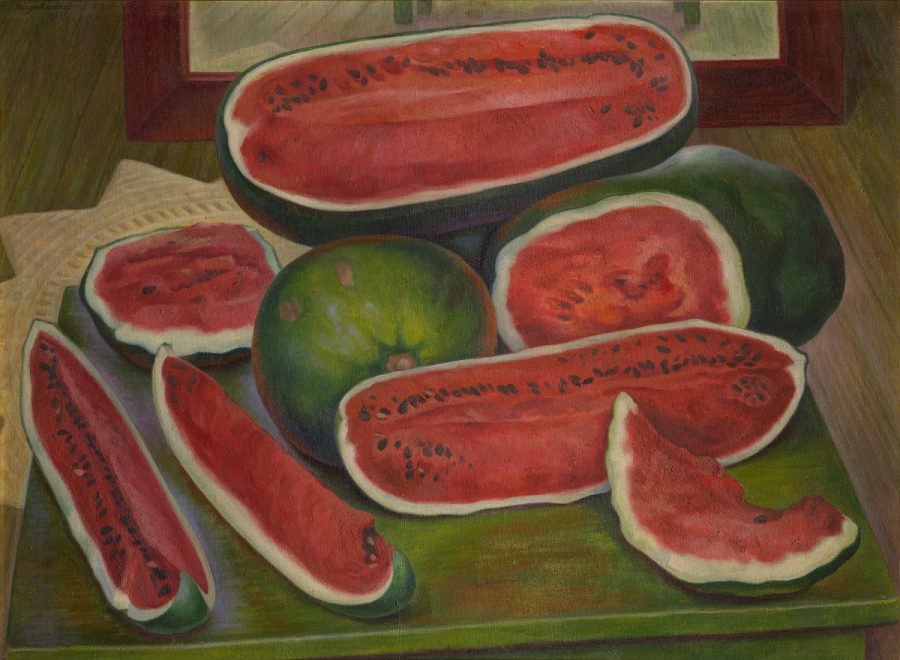

His final painting, The Watermelons, a very Mexican subject that’s also a tribute to Kahlo’s last work, Viva La Vida…

And a locked bathroom in which he decreed 6,000 photographs, 300 of Kahlo’s garments and personal items, and 12,000 documents were to be housed until 15 years after his death.

Among the many revelations when this chamber was belatedly unsealed in 2004, her clothing caused the biggest stir, particularly the ways in which the colorful garments were adapted to and informed by her physical disabilities.

Her prosthetic leg, shod in an eye-catching red boot was given a place of honor in an exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum.,

These treasures might have come to light earlier save for a judgment call on the part of Dolores Olmedo, Rivera’s patron, former model, and friend. During renovations to turn the couple’s home into a museum, she had a peek and decided the lipstick-imprinted love letters from some famous men Frida had bedded could damage Rivera’s reputation.

In what way, it’s difficult to parse.

The couple’s history of extramarital relations (including Rivera’s dalliance with Kahlo’s sister, Christina) weren’t exactly secret, and both of the players had left the building.

One thing that’s taken for granted is Kahlo’s passion for Rivera, whom she met as girl of 15. Tempting as it might be to view the relationship with 2020 goggles, it would be a disservice to Kahlo’s sense of her own narrative. Self-examination was central to her work. She was characteristically avid in letters and diary entries, detailing her physical attraction to every aspect of Rivera’s body, including his giant belly “drawn tight and smooth as a sphere.” Ditto her obsession with his many conquests.

Not surprisingly, she was capable of penning a pretty spicy love letter herself, and the majority were aimed at her husband:

Nothing compares to your hands, nothing like the green-gold of your eyes. My body is filled with you for days and days. you are the mirror of the night. the violent flash of lightning. The dampness of the earth. The hollow of your armpits is my shelter. my fingers touch your blood. All my joy is to feel life spring from your flower-fountain that mine keeps to fill all the paths of my nerves which are yours.

Her most notorious love letter does not appear to be one at first.

Bedridden, and facing the amputation of a gangrenous right leg that had already sacrificed some toes 20 years earlier, she directed the full force of her emotions at Rivera.

The lover she’d tenderly pegged as “a boy frog standing on his hind legs” now appeared to her an “ugly son of a bitch,” maddeningly possessed of the power to seduce women (as he had seduced her).

You have to read all the way to the twist:

Mexico,

1953My dear Mr. Diego,

I’m writing this letter from a hospital room before I am admitted into the operating theatre. They want me to hurry, but I am determined to finish writing first, as I don’t want to leave anything unfinished. Especially now that I know what they are up to. They want to hurt my pride by cutting a leg off. When they told me it would be necessary to amputate, the news didn’t affect me the way everybody expected. No, I was already a maimed woman when I lost you, again, for the umpteenth time maybe, and still I survived.

I am not afraid of pain and you know it. It is almost inherent to my being, although I confess that I suffered, and a great deal, when you cheated on me, every time you did it, not just with my sister but with so many other women. How did they let themselves be fooled by you? You believe I was furious about Cristina, but today I confess that it wasn’t because of her. It was because of me and you. First of all because of me, since I’ve never been able to understand what you looked and look for, what they give you that I couldn’t. Let’s not fool ourselves, Diego, I gave you everything that is humanly possible to offer and we both know that. But still, how the hell do you manage to seduce so many women when you’re such an ugly son of a bitch?

The reason why I’m writing is not to accuse you of anything more than we’ve already accused each other of in this and however many more bloody lives. It’s because I’m having a leg cut off (damned thing, it got what it wanted in the end). I told you I’ve counted myself as incomplete for a long time, but why the fuck does everybody else need to know about it too? Now my fragmentation will be obvious for everyone to see, for you to see… That’s why I’m telling you before you hear it on the grapevine. Forgive my not going to your house to say this in person, but given the circumstances and my condition, I’m not allowed to leave the room, not even to use the bathroom. It’s not my intention to make you or anyone else feel pity, and I don’t want you to feel guilty. I’m writing to let you know I’m releasing you, I’m amputating you. Be happy and never seek me again. I don’t want to hear from you, I don’t want you to hear from me. If there is anything I’d enjoy before I die, it’d be not having to see your fucking horrible bastard face wandering around my garden.

That is all, I can now go to be chopped up in peace.

Good bye from somebody who is crazy and vehemently in love with you,

Your Frida

This is a love letter masquerading as a doozy of a break up letter. The references to amputation are both literal and metaphorical:

No doubt, she was sincere, but this couple, rather than holding themselves accountable, excelled at reversals. In the end the letter’s threat proved idle. Shortly before her death, the two appeared together in public, at a demonstration to protest the C.I.A.’s efforts to overthrow the leftist Guatemalan regime.

Image via Brooklyn Museum

Once Frida was safely laid to rest, by which we mean rumored to have sat bolt upright as her casket was slid into the incerator, Rivera mused in his autobiography:

Too late now I realized the most wonderful part of my life had been my love for Frida. But I could not really say that given “another chance” I would have behaved toward her any differently than I had. Every man is the product of the social atmosphere in which he grows up and I am what I am…I had never had any morals at all and had lived only for pleasure where I found it. I was not good. I could discern other people’s weaknesses easily, especially men’s, and then I would play upon them for no worthwhile reason. If I loved a woman, the more I wanted to hurt her. Frida was only the most obvious victim of this disgusting trait.

via Letters of Note and the book, Letters of Note: Love.

Related Content:

Take a Virtual Tour of Frida Kahlo’s Blue House Free Online

What the Iconic Painting, “The Two Fridas,” Actually Tells Us About Frida Kahlo

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.