In the winter of 2012, just before Christmas, a carful of Britons made their way through the snow to a house in rural France. The roads would soon close, but no matter; they’d planned to make some apple crumbles, do some drawing, and enjoy some conversation. This may all sound normal enough, but the car didn’t contain your average cottage-staying holidaymakers: the critic and filmmaker Colin MacCabe rode in it, as did Tilda Swinton, the actress as famed for her performances as for her range of artistic and intellectual interests. They’d come to shoot a documentary on the occupant of the house at which they’d arrived: artist, critic, writer, and self-described “storyteller” John Berger.

The novel G. won Berger the Booker prize in 1972 (half of the prize money from which he famously donated to Britain’s Black Panther Party), but most of his readers encounter him through that same year’s Ways of Seeing, a text on the ideology of images that ranks among the twenty most influential academic books of all time.

He and Swinton first became friends in the late 1980s, when she played a small part in a film based on one of his short stories, in which he himself also appeared. “The old intellectual and the young actress immediately formed a close bond,” writes The Independent’s Geoffrey McNab.

“Both were born in London, on 5 November — Berger in 1926, Swinton in 1960 — and their shared birthday has, as Swinton puts it, ‘formed a bedrock to our complicity, the practical fantasy of twinship.’ ” This they discuss in the McCabe-directed “Ways of Listening,” the first of a quartet of segments that constitute the new documentary The Seasons In Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger, a co-production of Birkbeck, University of London’s Derek Jarman Lab. “Sometimes I think it’s as though, in another life, we met or did something,” says Berger as he draws Swinton’s portrait. “We are aware of it in some department which isn’t memory, although it’s quite close to memory. Maybe, in another life, we… touched together.”

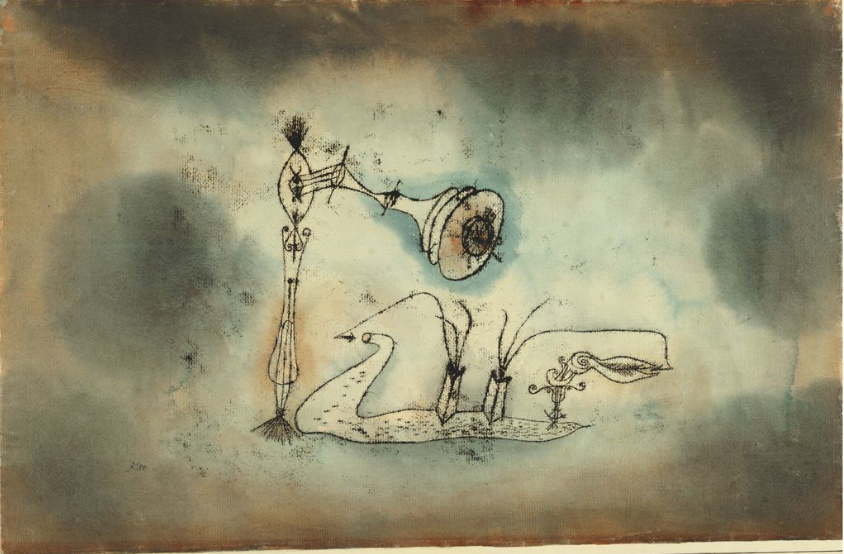

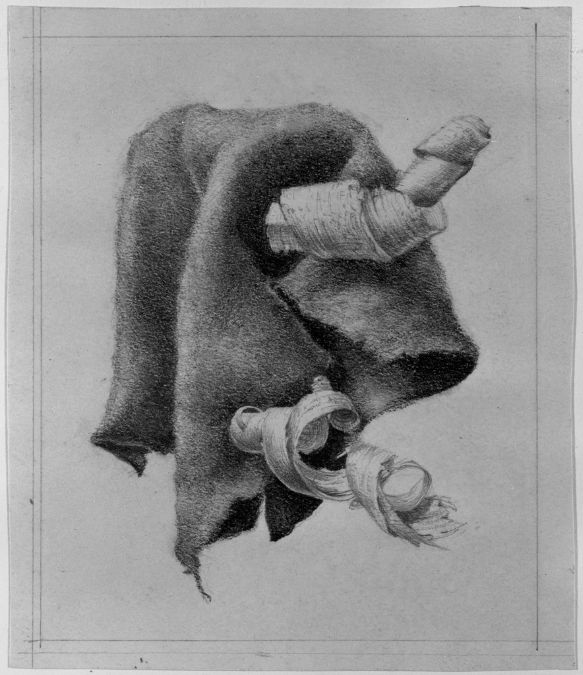

“Ways of Listening” captures an extended conversation between Berger and Swinton, though it also features their narration. In this scene, Berger reads from his recent meditation on the practice of drawing for his book Bento’s Sketchbook: “We who draw do so not only to make something visible to others, but also to accompany something invisible to its incalculable destination.” (Swinton, for her part, reads from Spinoza.) But the talk returns to what brought them together in the first place. “Maybe we made an appointment to see each other again, in this life,” Berger proposes. “The fifth of November. But it wasn’t the same year. That didn’t matter. We weren’t in that kind of time.”

“We got off at the same station.”

“Exactly.”

Related Content:

Tilda Swinton Recites Poem by Rumi While Reeking of Vetiver, Heliotrope & Musk

Wittgenstein: Watch Derek Jarman’s Tribute to the Philosopher, Featuring Tilda Swinton (1993)

Watch David Bowie’s New Video for ‘The Stars (Are Out Tonight)’ With Tilda Swinton

The 20 Most Influential Academic Books of All Time: No Spoilers

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.