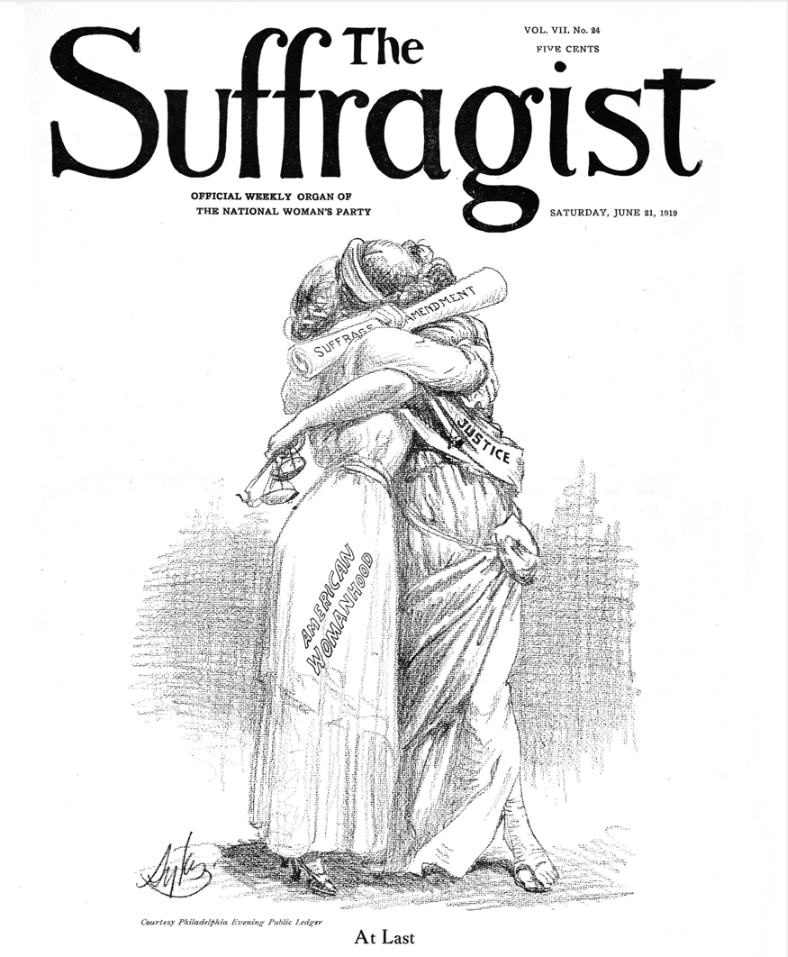

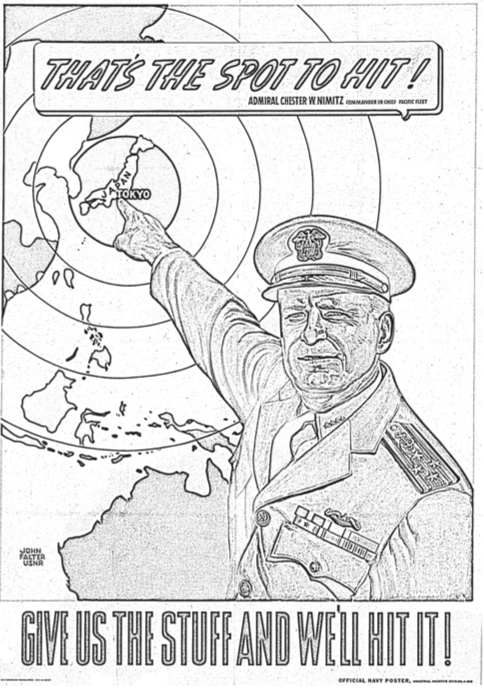

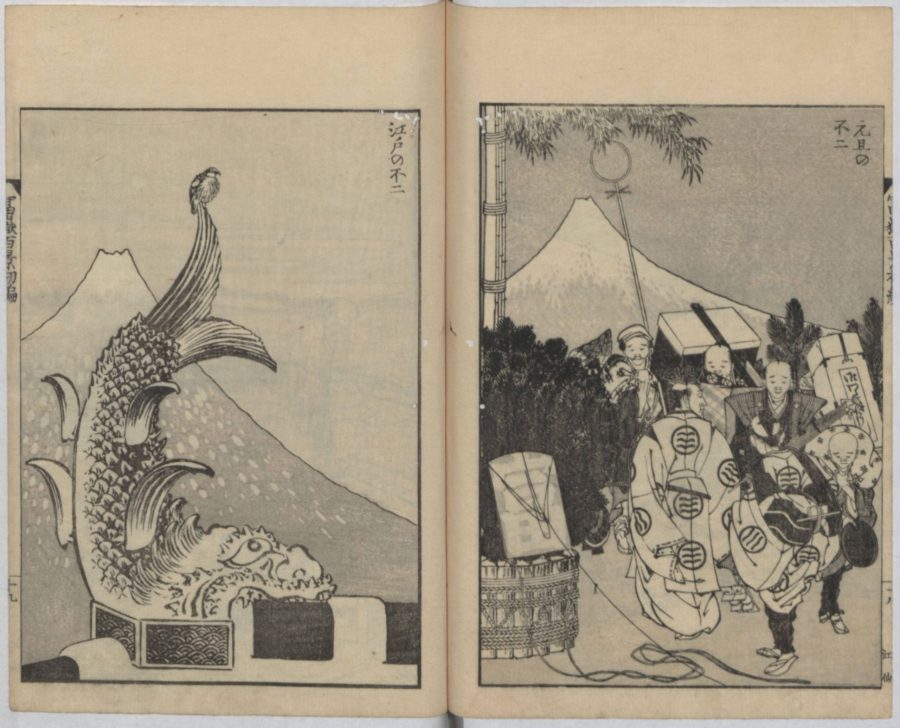

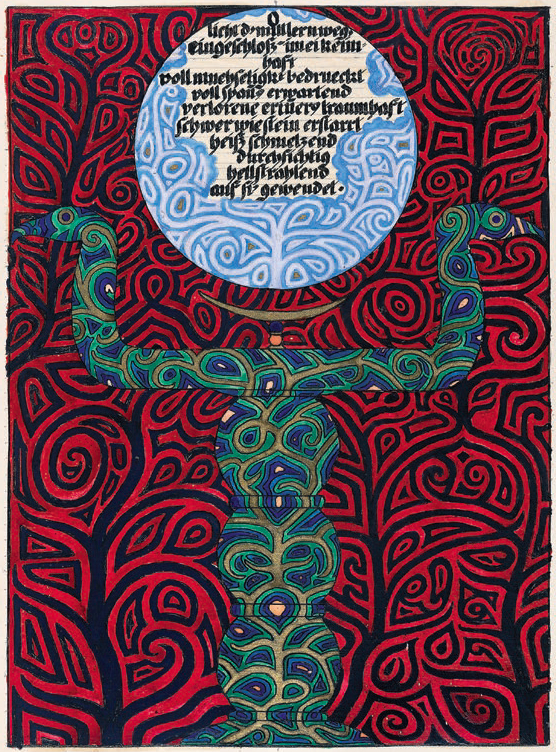

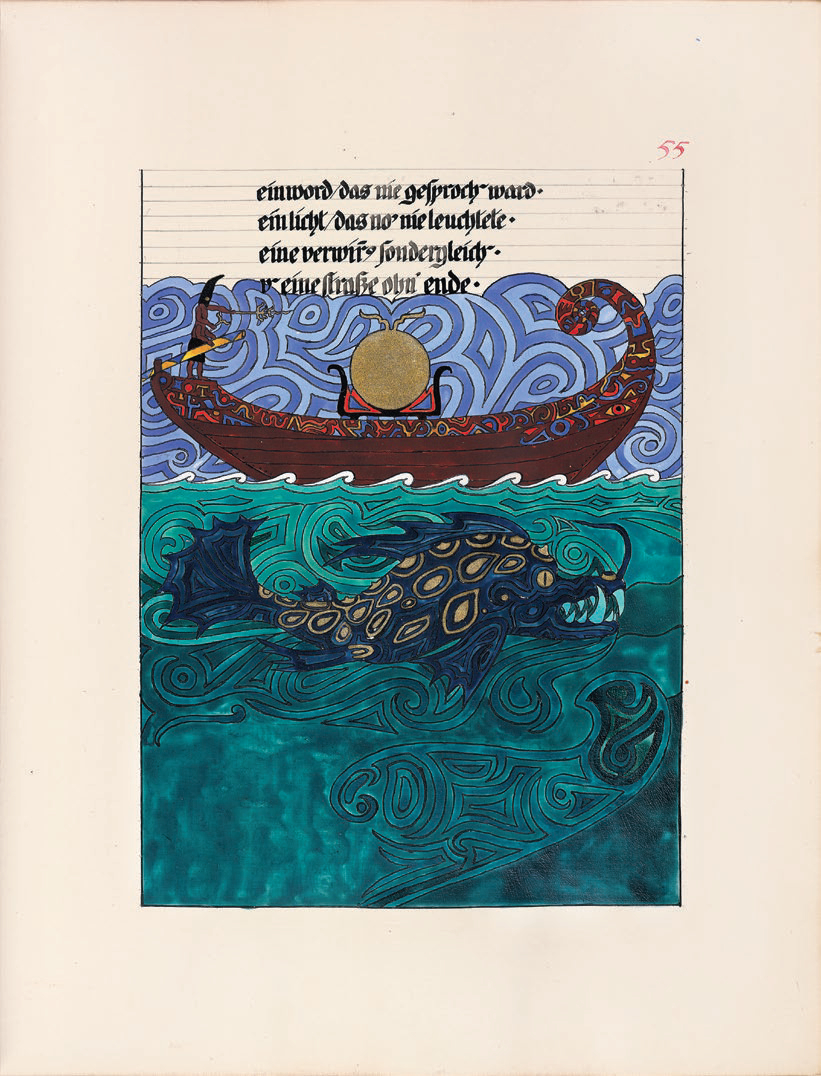

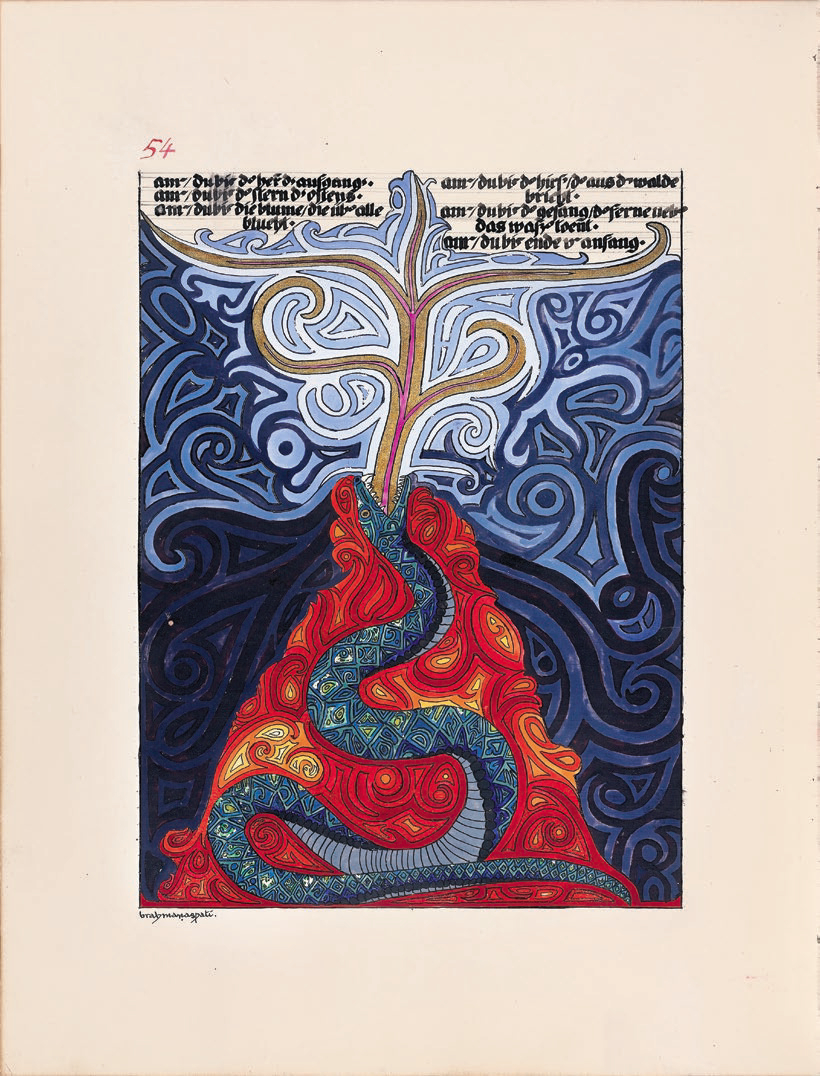

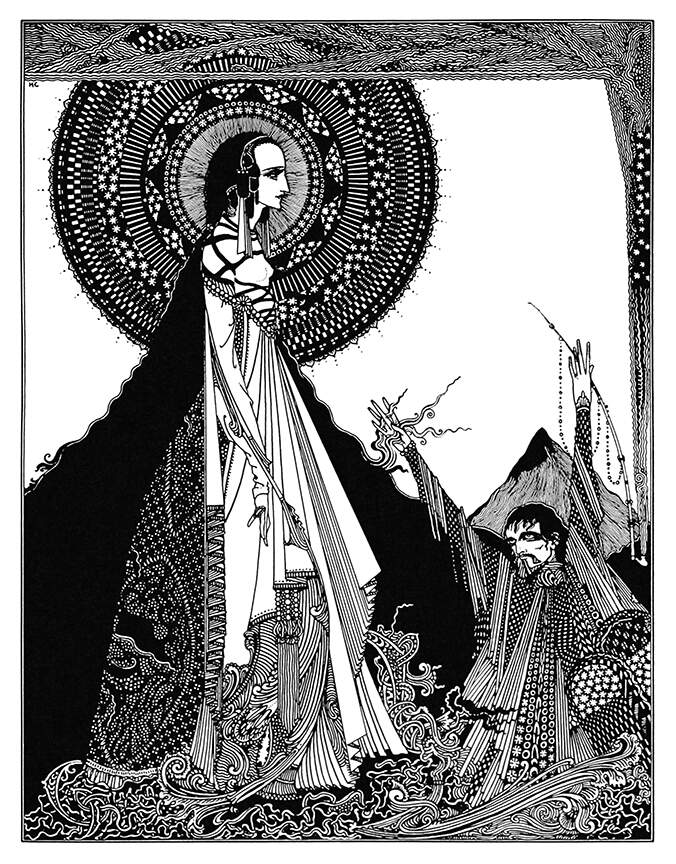

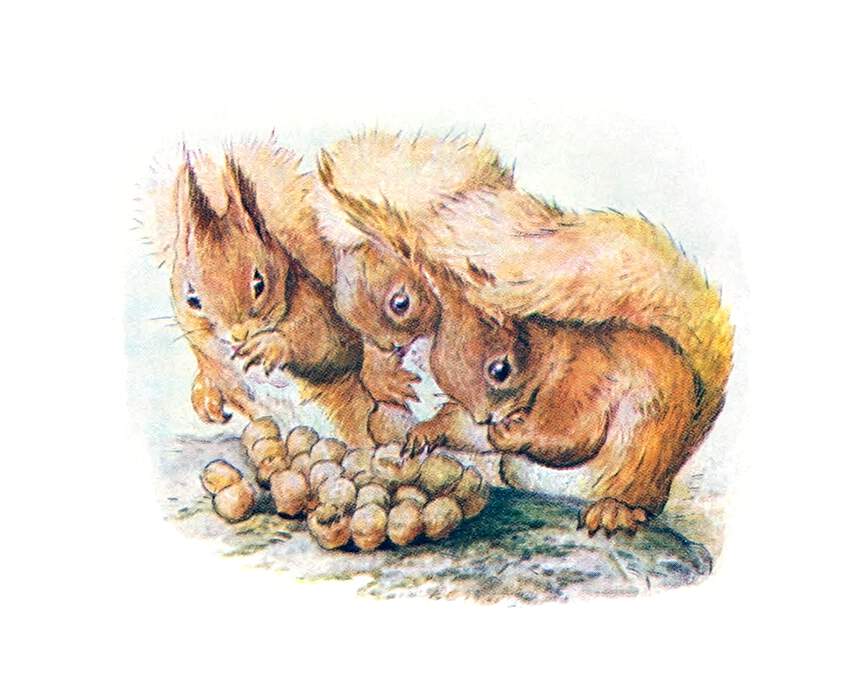

The Golden Age of Illustration is typically dated between 1880 and the early decades of the 20th century. This was “a period of unprecedented excellence in book and magazine illustration,” writes Artcyclopedia; the time of artists like John Tenniel, Beatrix Potter (below), Arthur Rackham, and Aubrey Beardsley. Some of the most prominent illustrators, such as Beardsley and Harry Clarke (see one of his Poe illustrations above), also became internationally known artists in the Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts, and Pre-Raphaelite movements.

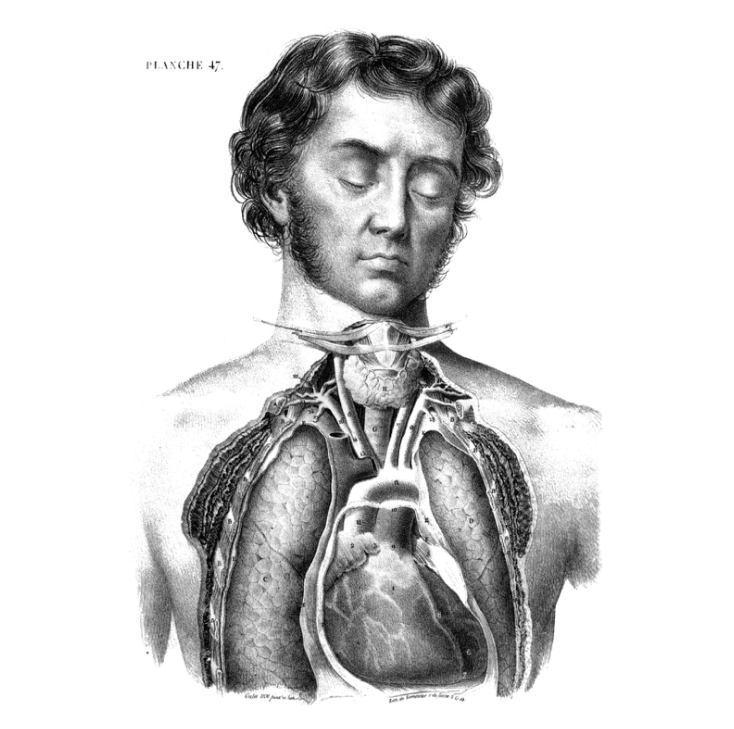

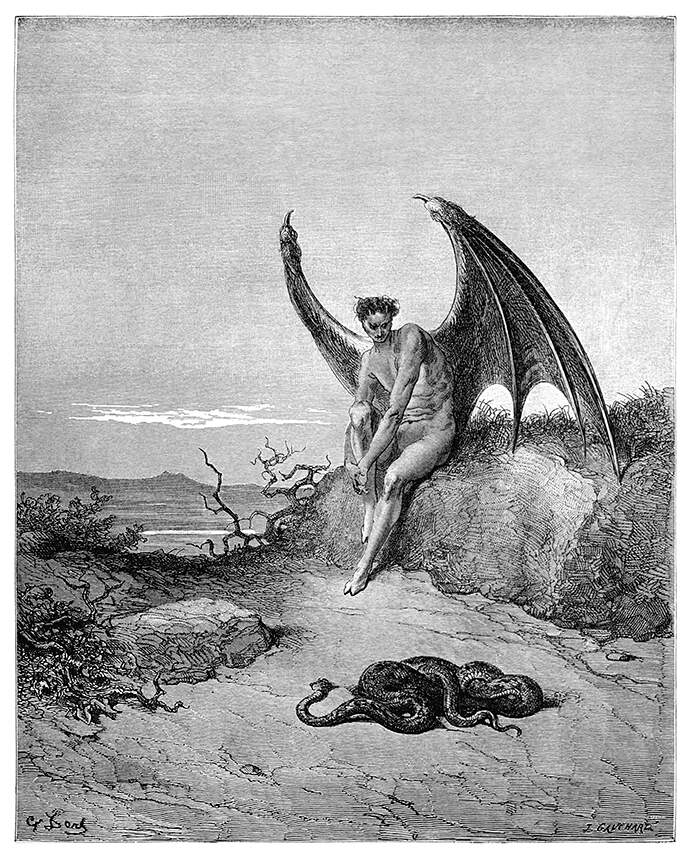

But extensive book illustration as the primary visual culture of print precedes this period by several decades. One of the most revered and prolific of fine art book illustrators, Gustave Doré, did some of his best work in the mid-nineteenth century.

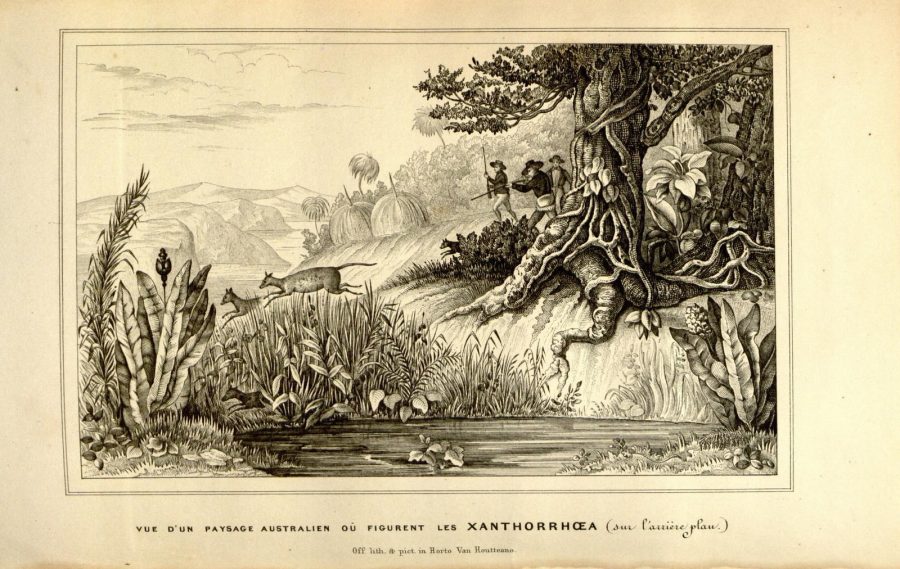

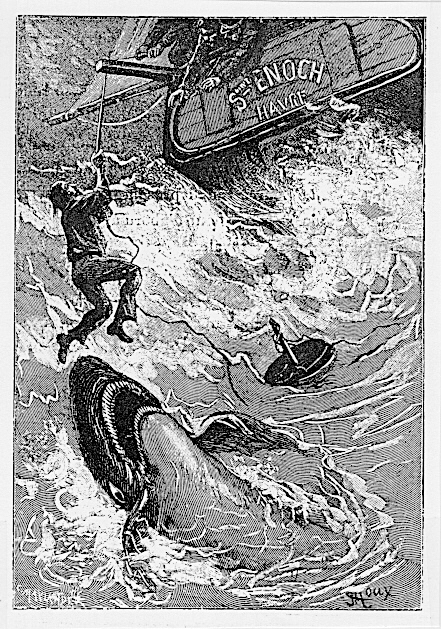

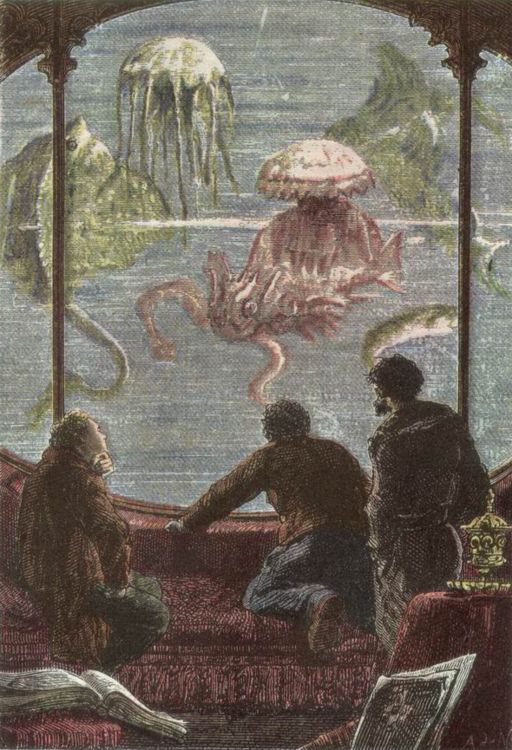

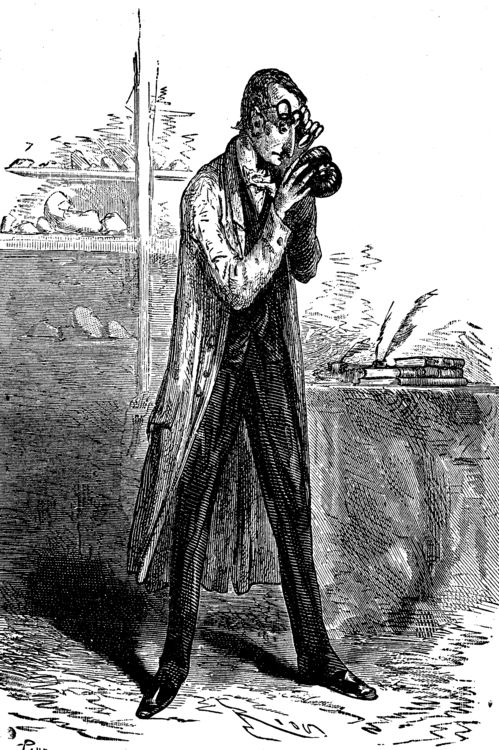

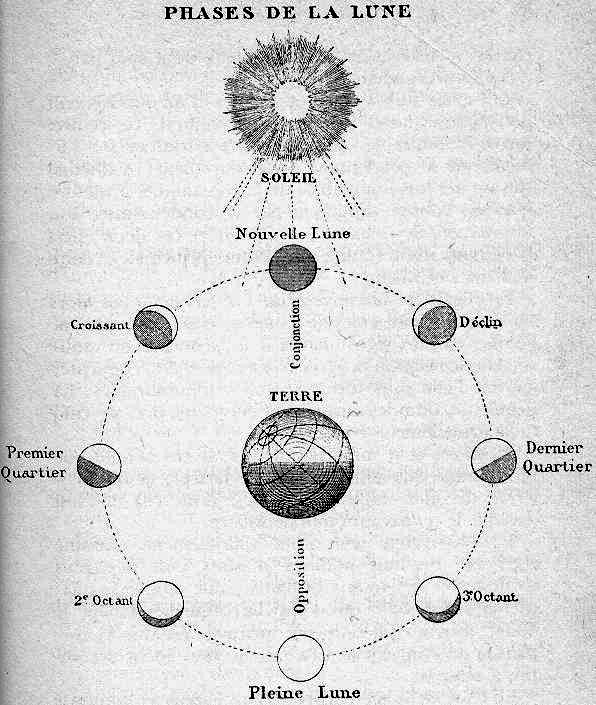

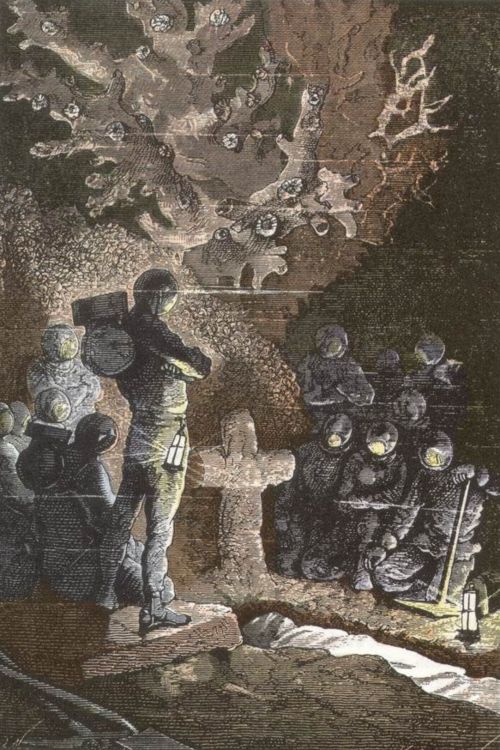

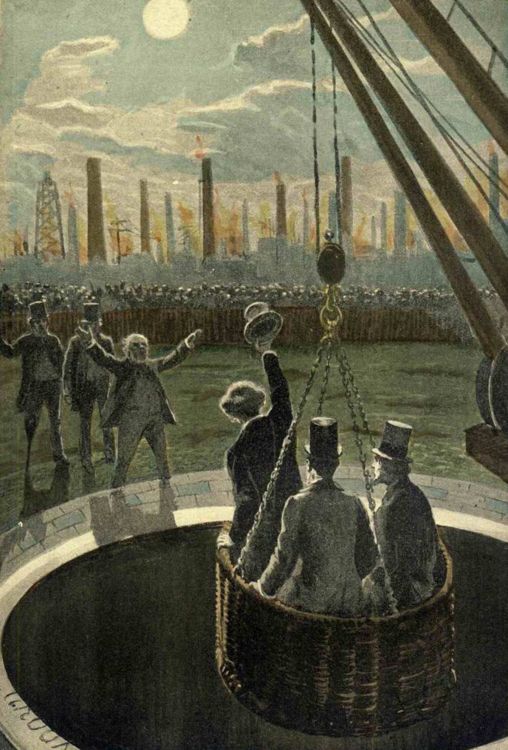

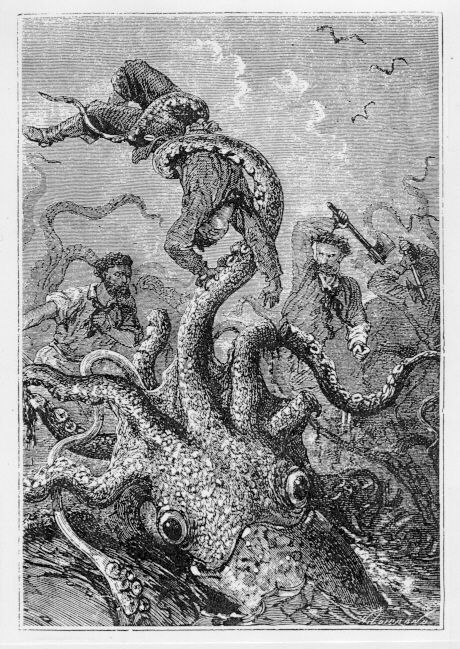

Other French illustrators, such as Alphonse de Neuville and Emile-Antoine Bayard, made impressive contributions in the 1860s and 70s—for example, to Jules Verne’s lavishly illustrated, 54-volume Voyages Extraordinaires.

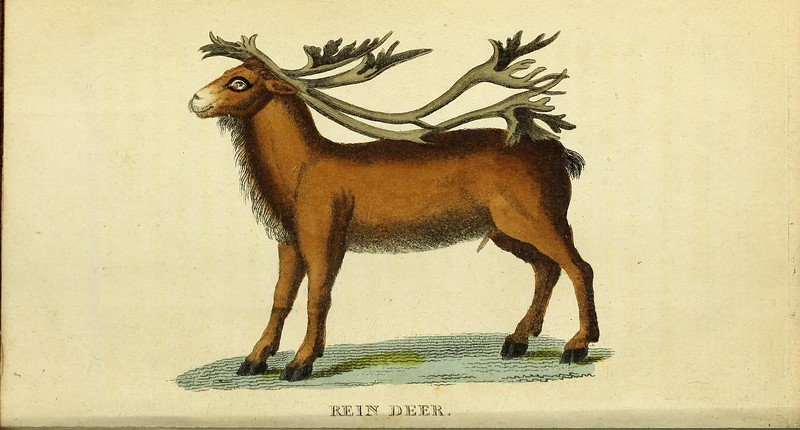

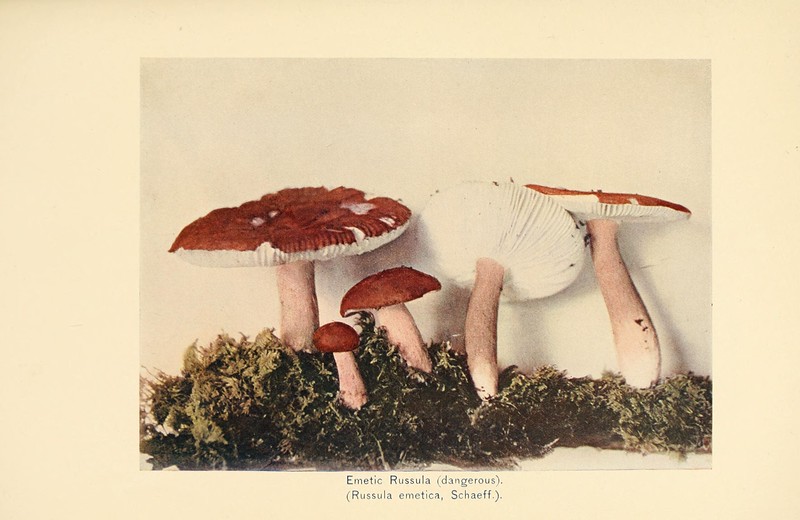

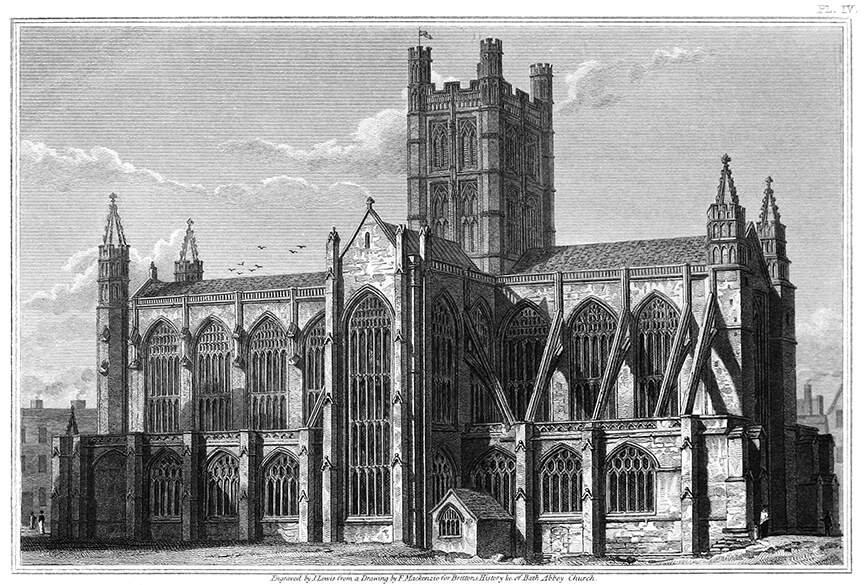

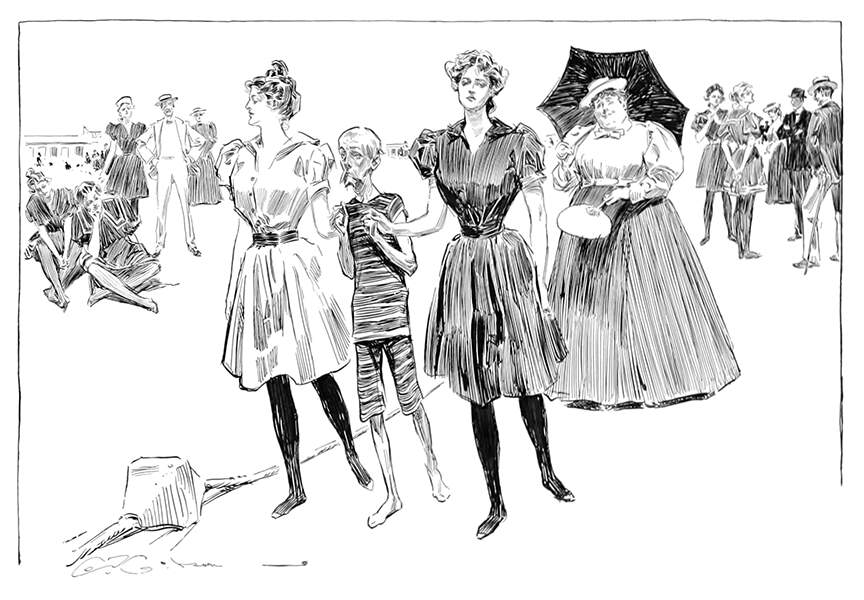

As Colin Marshall wrote in a recent post here, these copious illustrations (4,000 in all) served more than a just decorative purpose. A less than “fully literate public” benefited from the picture-book style. So too did readers hungry for stylish visual humor, for documentary representations of nature, architecture, fashion, etc., before photography became not only possible but also inexpensive to reproduce. Whatever the reason, readers throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would generally expect their reading material to come with pictures, and very finely rendered ones at that.

The online database Old Book Illustrations has catalogued thousands of these illustrations, lifted from their original context and searchable by artist name, source, date, book title, techniques, formats, publishers, subject, etc. “There are also a number of collections to browse through,” notes Kottke, “and each are tagged with multiple keywords.” Not all of the work represented here is up to the uniquely high standards of a Gustave Doré (below), Aubrey Beardsley, or John Tenniel, all of whom, along with hundreds of other artists, get their own categories. But that’s not entirely the point of this library.

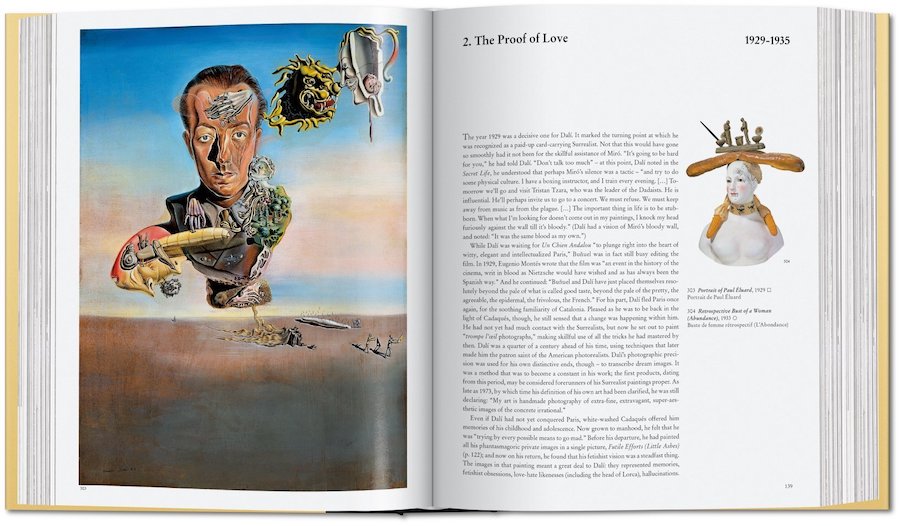

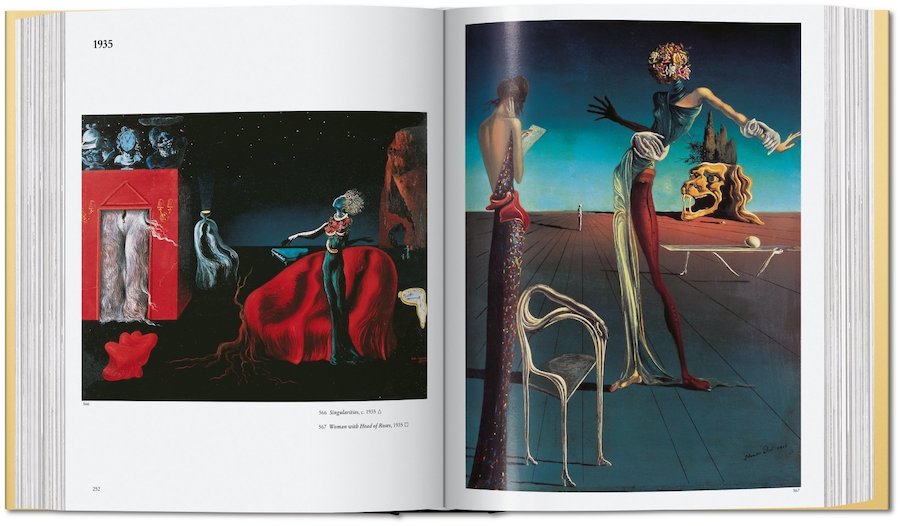

Old Book Illustrations presents itself as a scholarly resource, including a digitized Dictionary of the Art of Printing and short articles on some of the most famous artists and significant texts from the period. The site’s publishers are also transparent about their selection process. They are guided by their “reasons pertaining to taste, consistency, and practicality,” they write. The archive might have broadened its focus, but “due to obvious legal restrictions, [they] had to stay within the limits of the public domain.”

Likewise, they note that the digitized images on the site have been restored to “make them as close as possible to the perfect print the artist probably had in mind when at work.” Visitors who would prefer to see the illustrations as “time handed them to us” can click on “Raw Scan” to the right of the list of resolution options at the top of each image. (See a processed and unprocessed scan above and below of fashion illustrator and humorist Charles Dana Gibson’s “overworked American father” on “his day off in August.”)

All of the images on Old Book Illustrations are available in high resolution, and the site authors intend to add more articles and to make available in English articles on French Romanticism unavailable anywhere else. “We are not the only image collection on the web,” they write, “neither will we ever be the largest one. We hope however to be a destination of choice for visitors more particularly interested in Victorian and French Romantic illustrations.” They give visitors who fit that description plenty of incentive to keep coming back.

Related Content:

Aubrey Beardsley’s Macabre Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Short Stories (1894)

Harry Clarke’s Hallucinatory Illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories (1923)

Gustave Doré’s Splendid Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness