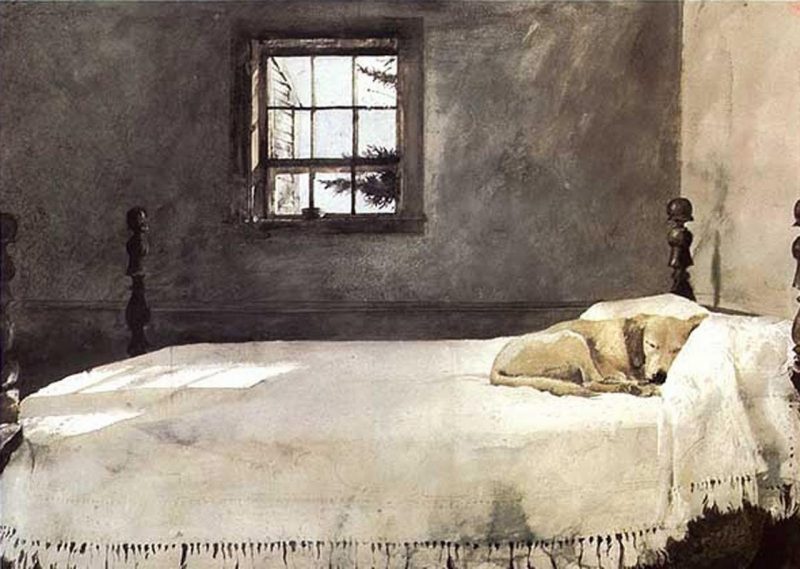

Though born in the late 19th century and partially shaped by a few sojourns to Europe, Edward Hopper was an artist fundamentally of early 20th-century America. He took life in that time and place as his subject, but he also once said that “an artist paints to reveal himself through what he sees in his subject,” meaning that he in some sense embodied early 20th-century America. Royal Academy of the Arts Artistic Director Tim Marlow quotes that line in the 60-second introduction to Hopper above, then points to a common thread in the painter’s “enigmatic works”: a “profound contemplation of the world around us” that turns each of his paintings into one captured “moment of stillness in a frantic world.”

Much of Hopper’s work came out of the Great Depression, “a period of great uncertainty and anxiety, but also a time of deep national self-imagination about the very idea of American-ness.” To look at the figures who inhabit Hopper’s thoroughly American settings — a gas station, a hotel room, inside a train car, an all-night diner — self-reflection would seem to be their main pastime.

“A woman sits alone drinking a cup of coffee,” says the School of Life’s head of Art and Architecture Hanna Roxburgh of Hopper’s 1927 Automat in the video above. “She seems slightly self-conscious and a little afraid. Perhaps she’s not used to sitting alone in a public space. Something seems to have gone wrong. The view is invited to invent stories for her of betrayal or loss.”

Loneliness, isolation, even despair: these words tend to come up in discussion of the moods of Hopper’s characters, as well as of his paintings themselves. In the in-depth exploration above, Colin Wingfield focuses on a single emotion expressed in Hopper’s work: alienation. A product of the “machine age” in late 19th- and early 20th century America, Hopper expressed an uneasy view of the ways in which accelerating industrialization and automation were altering the lives lived around him into unrecognizability. This view would turn out to have an enormous cultural resonance, as detailed in Edward Hopper and the Blank Canvas, the hourlong documentary below.

Touching on the Hopper influences seen in the work of directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Terrence Malick as well as television shows like Mad Men and The Simpsons, Edward Hopper and the Blank Canvas also brings in cultural figures like the German filmmaker Wim Wenders, an avowed Hopper enthusiast with much to say about the painter’s vision in America. More creators from the world of cinema appear in the video below to offer their personal perspectives on Hopper’s considerable influence on their art form — an art form that had considerable influence on Hopper, an avid moviegoer since he first watched a motion picture in Paris in 1909.

No single painting of Hopper’s has had as much influence on film as 1942’s Nighthawks, by far the painter’s best-known work. How exactly he achieved his own cinematic effects in a still image, such as the “storyboarding” technique with which he developed its composition, is a subject we’ve featured before here on Open Culture. In the video essay “Nighthawks: Look Through the Window,” Evan Puschak — better known as the Nerdwriter — seeks out the sources of the painting’s enduring power, from its “clean, smooth, and almost too real” aesthetic to its rigorous composition to its host of visual elements meant to both compel and unsettle the viewer.

Hopper explains his way of working in his own words in the short video from the Walker Art Center below. “It’s a long process of gestation in the mind and a rising emotion,” he says, followed by “drawings, quite often many drawings”: “various small sketches, sketches of the thing that i wish to do, also sketches of details in the picture.” As for the themes of “loneliness, isolation, modern man and his man-made environment” so often ascribed to the final products, “those are the words of critics. It may be true and it may not be true. It’s how the viewer looks at the pictures, what he sees in them.”

Related Content:

How Edward Hopper “Storyboarded” His Iconic Painting Nighthawks

Edward Hopper’s Iconic Painting Nighthawks Explained in a 7‑Minute Video Introduction

9‑Year-Old Edward Hopper Draws a Picture on the Back of His 3rd Grade Report Card

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.