For thousands of years, ordinary people all over the world not only worked side-by-side with domestic animals on a daily basis, they also observed the wild fauna around them to learn how to navigate and survive nature. The closeness produced a keen appreciation for animal behavior that informs the folk tales of every continent and the popular texts of every religion. Our delight in animal stories survives in children’s books, but in grown-up language, animal comparisons tend to be nasty and dehumanizing. The demeaning adjective “bestial” conveys a typical attitude not only toward people we don’t like, but toward the animal world as well. Orwell’s Animal Farm and Kafka’s Metamorphosis have become the standard references for modern animal allegory.

Early literature shows us a range of different attitudes, where animals are treated as equals, with character traits both good and bad, or as noble messengers of a god or gods rather than livestock, moving scenery, or exploitable resources.

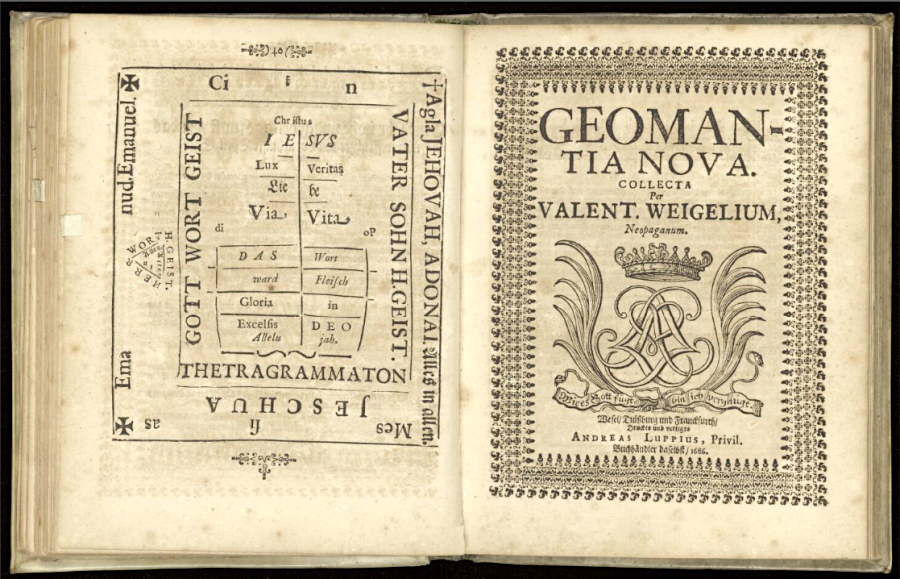

We might refer in an eastern context to the Jataka Tales, fables of the Buddha’s many rebirths in the human and animal worlds that provide their readers with moral lessons. In the Christian west, we have the medieval bestiary—compendiums of animals, both real and mythological—that introduced readers to a moral typology through “reading” what early Christians thought of as the “book of nature.”

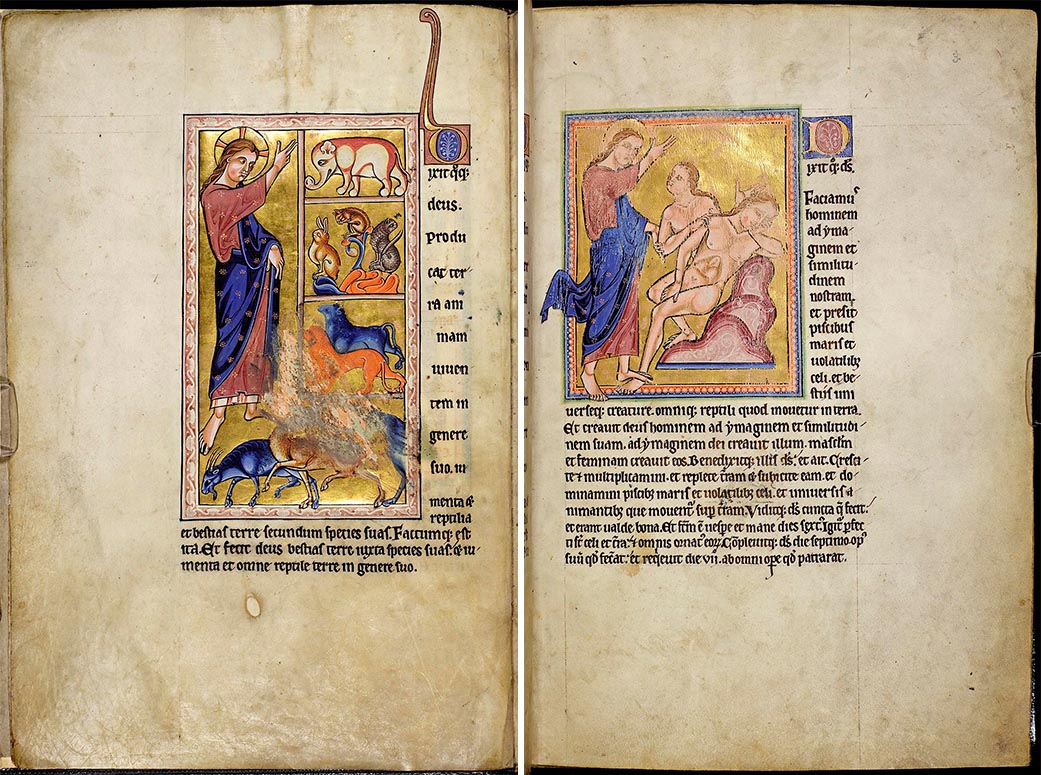

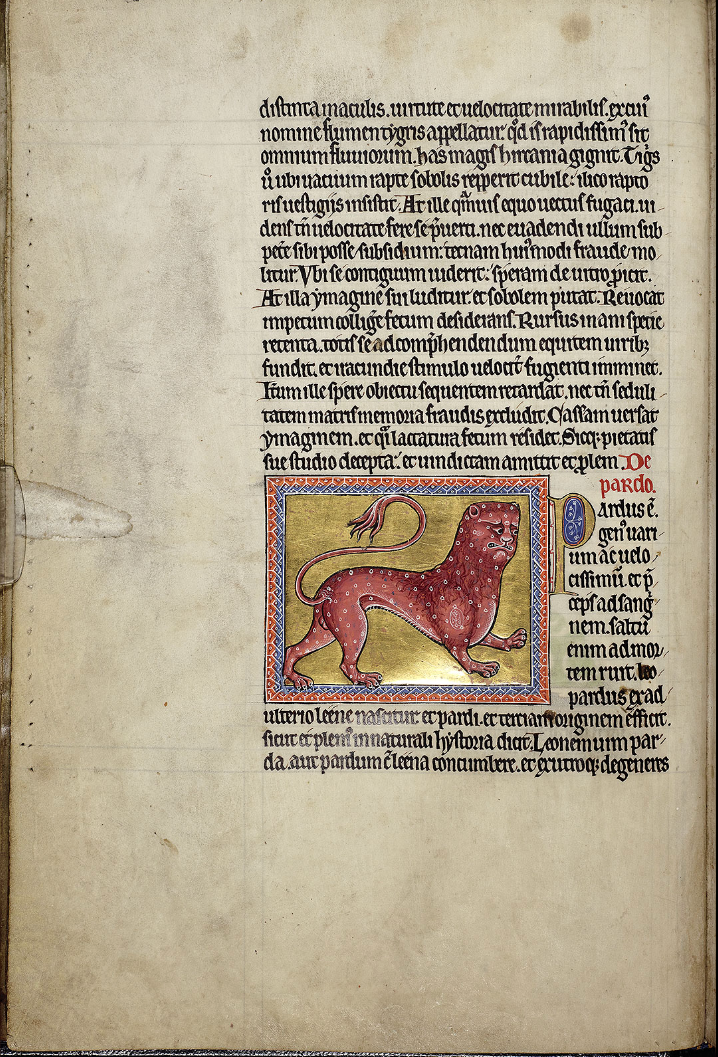

The most lavish of them all, the Aberdeen Bestiary, which dates from around 1200, was once owned by Henry VIII. Now, the University of Aberdeen has digitized the text and made it freely available to readers online. Beginning with the key creation stories from the book of Genesis, the book then dives into its descriptions of animals, beginning with the lion, the pard (panther), and the elephant.

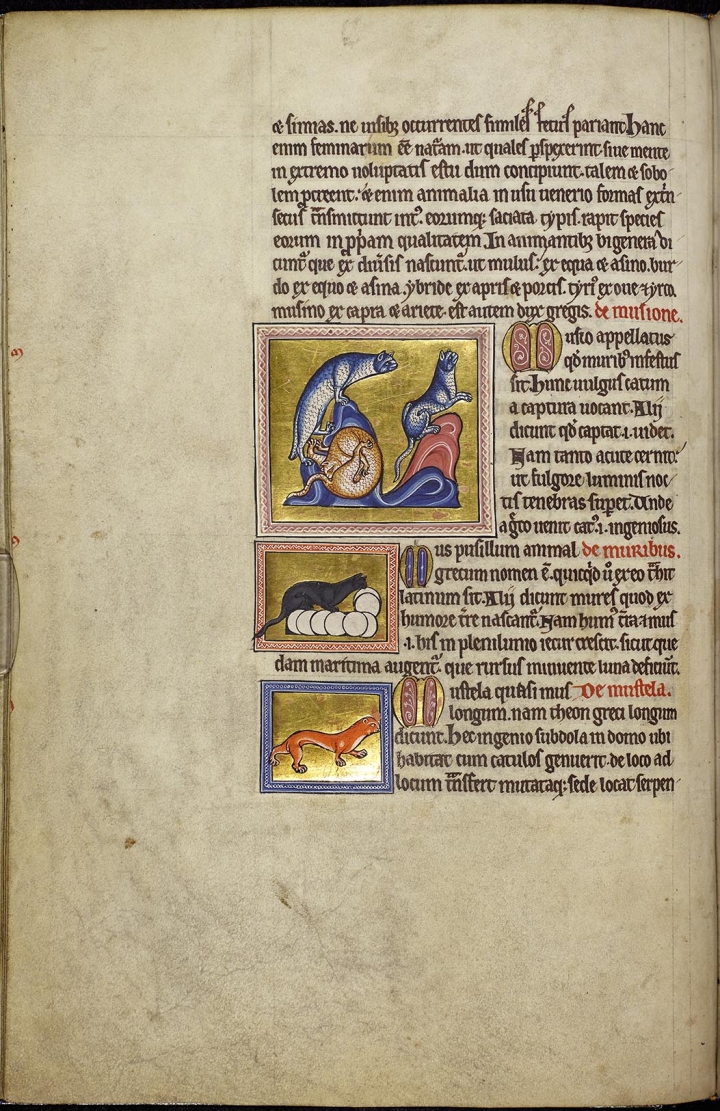

You’ll notice that these are not animals that your typical medieval European reader would have encountered. One important difference between the bestiary and the fable is that the former draws many of its beasts from hearsay, conjecture, or pure fiction. But the intent is partly the same. These “were teaching tools,” notes Claire Voon at Hyperallergic, and the Aberdeen Bestiary contains illustrated “lengthy tales of moral behavior.”

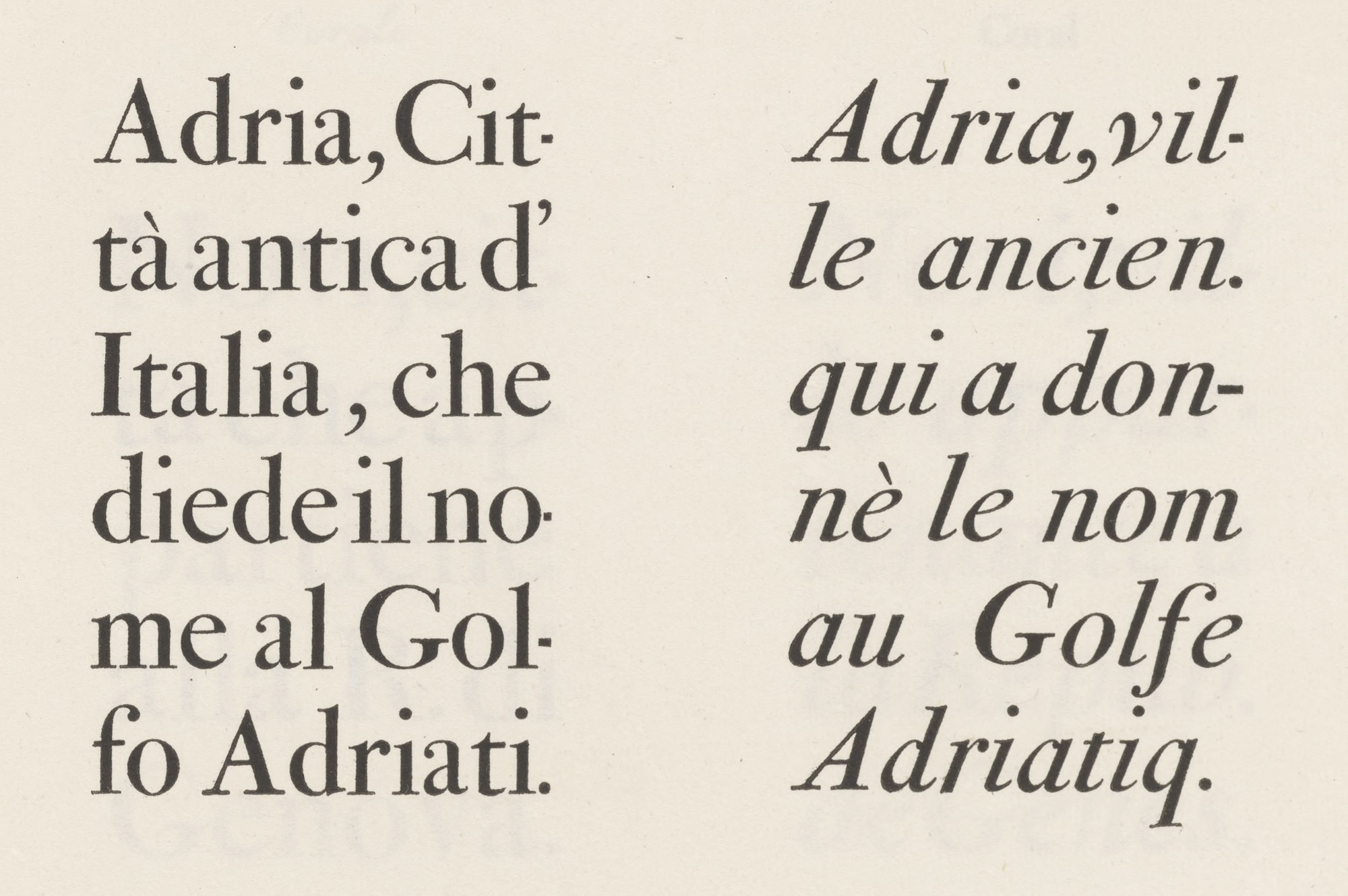

Like the stories of Aesop, the bestiary presents important lessons, mixing in the fabulous with the naturalist. As Voon describes the Aberdeen Bestiary:

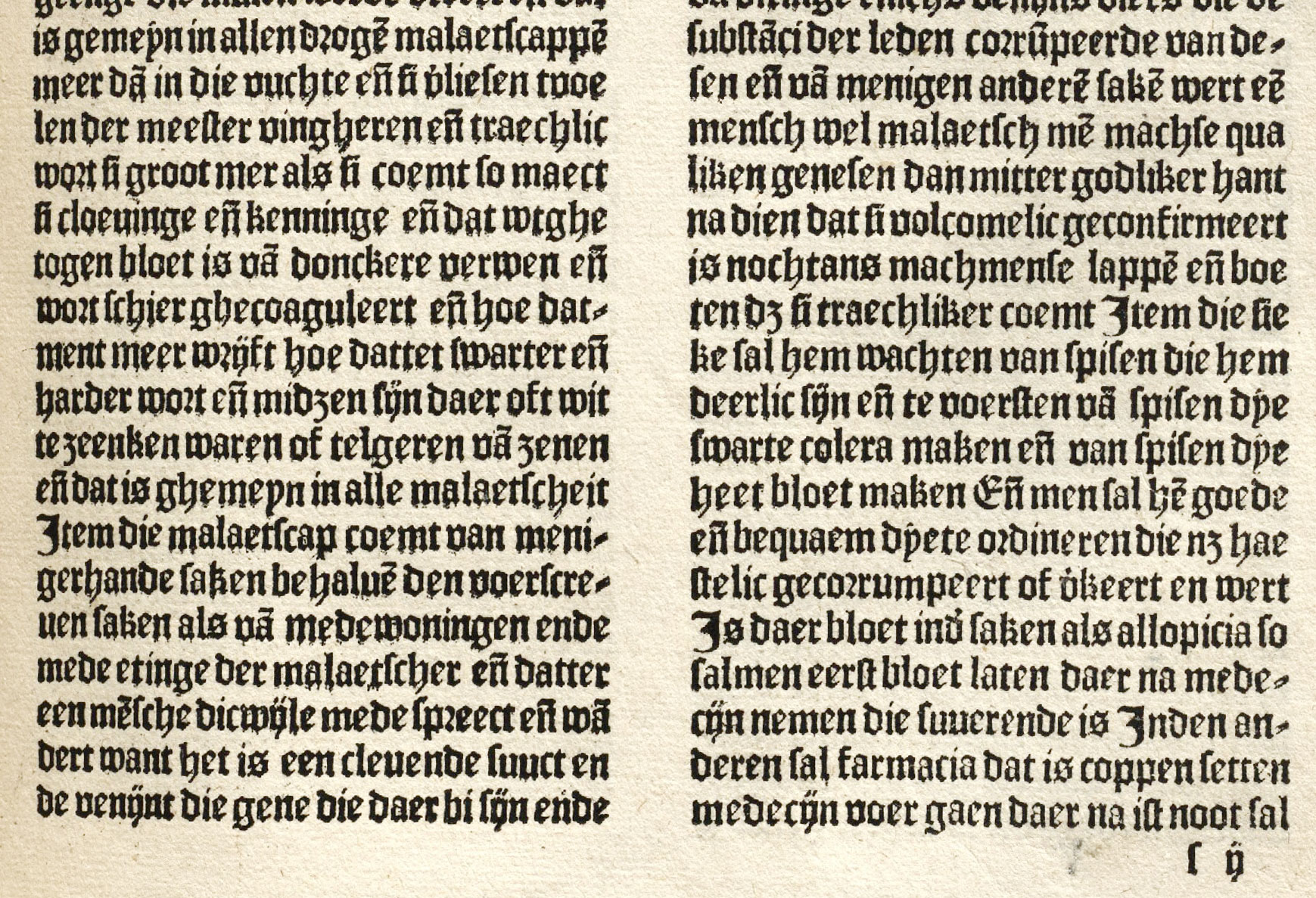

The illustrations are impressively varied, depicting common animals from tiny ants to elephants, as well as fantastic beasts, from the leocrota to the phoenix. Even the moral qualities of the humble sea urchin are honored with paragraphs of discussion. Beyond this array of creatures, the bestiary details the appearances and qualities of various trees, gems, and humans. Some of these may seem comical to 21st-century eyes: a swarm of bees, for instance, resembles an orderly line of shuttlecocks streaming into their hives. Yet other paintings are impressive for their near-accuracy, such as one image of a bat that shows how its membranous wings connect its fingers, legs, and tail. All of these rich details would have helped readers better understand the natural world as it was defined at the time of the book’s creation.

Incredibly ornate and bearing the marks of dozens of scribal hands, the book, historians believe, was originally produced for a wide audience, then taken by Henry’s librarians from a dissolved monastery. Never fully completed, it remained in the Royal Library for 100 years after Henry. “I doubt if the Tudor monarchs took it out for a regular read,” says Aberdeen University professor Jane Geddes. Now an open public document, it returns to its “original purpose of education,” writes Voon, “although for us, of course, it illuminates more about the past than the present.” See the high res scans here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

Related Content:

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Is Now Digitized and Available Online

How to Make a Medieval Manuscript: An Introduction in 7 Videos

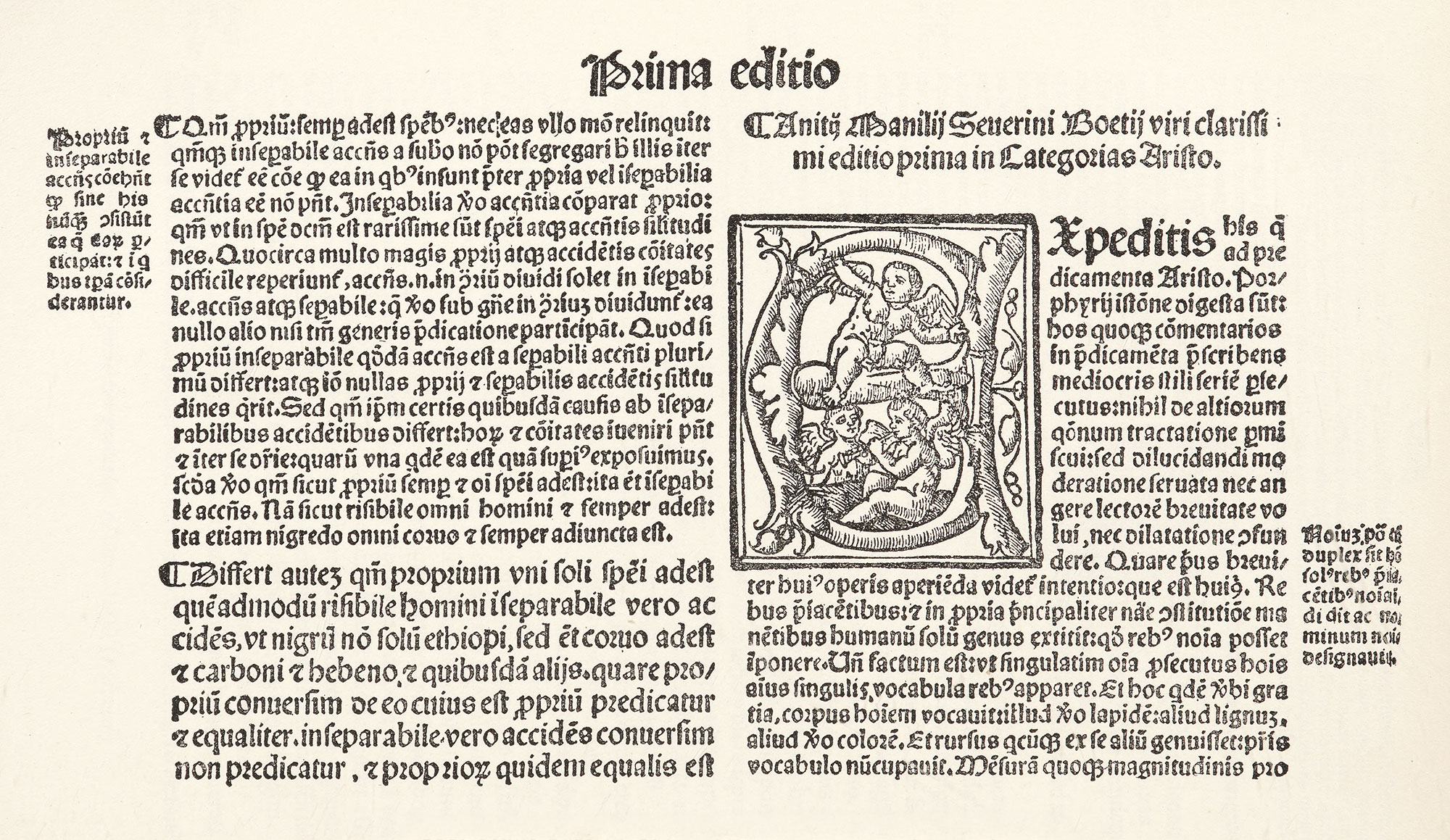

When Medieval Manuscripts Were Recycled & Used to Make the First Printed Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.