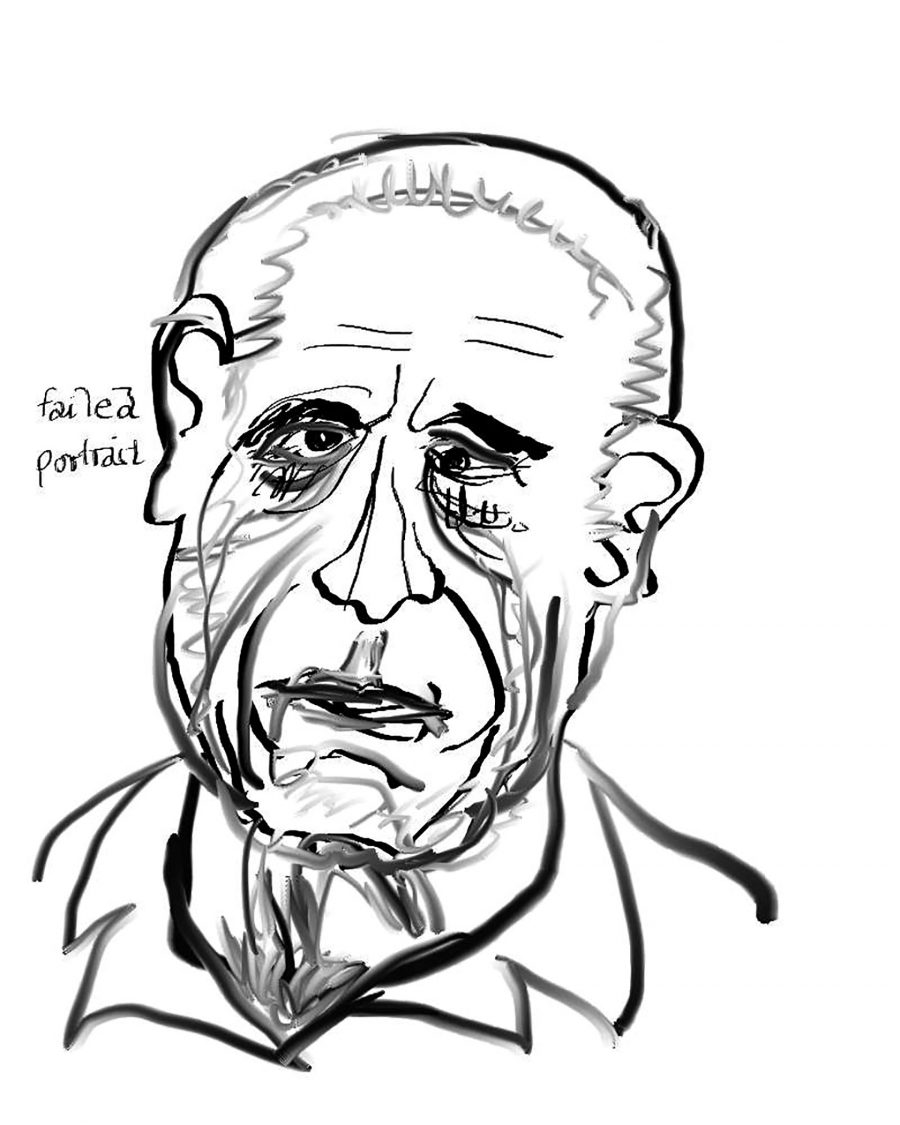

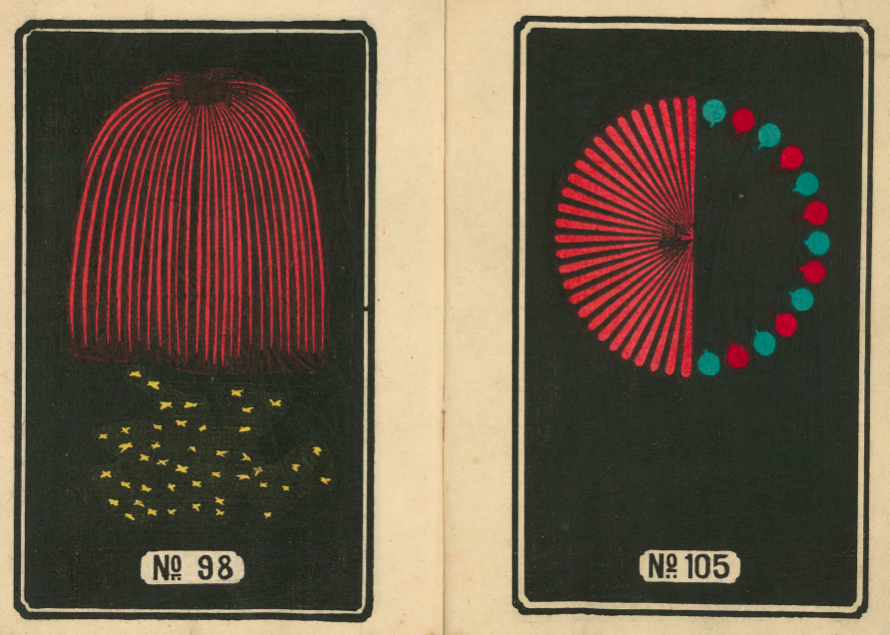

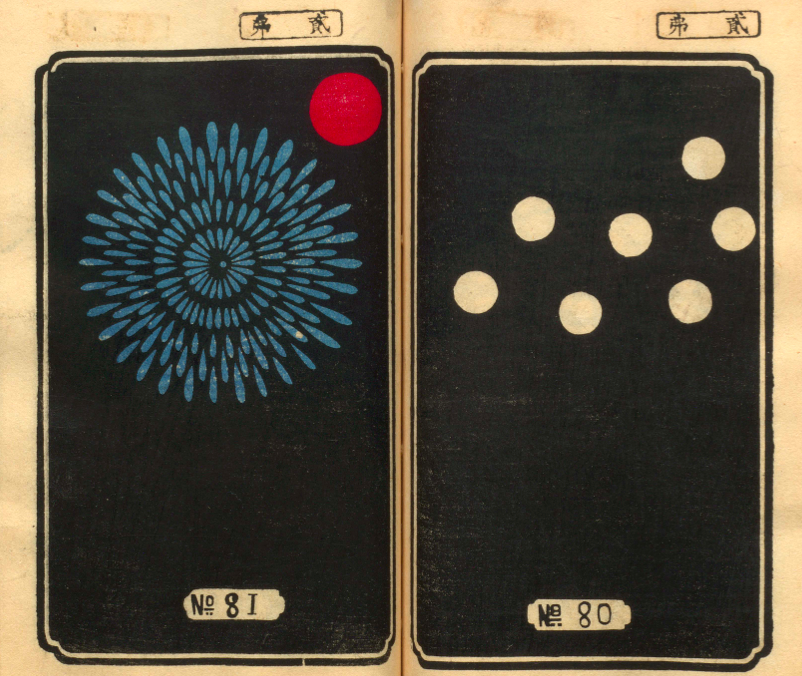

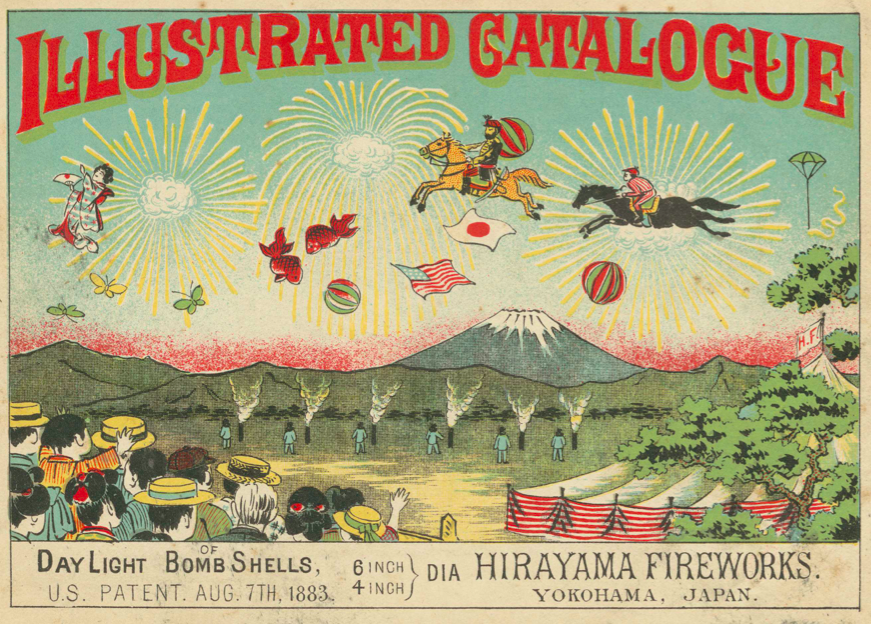

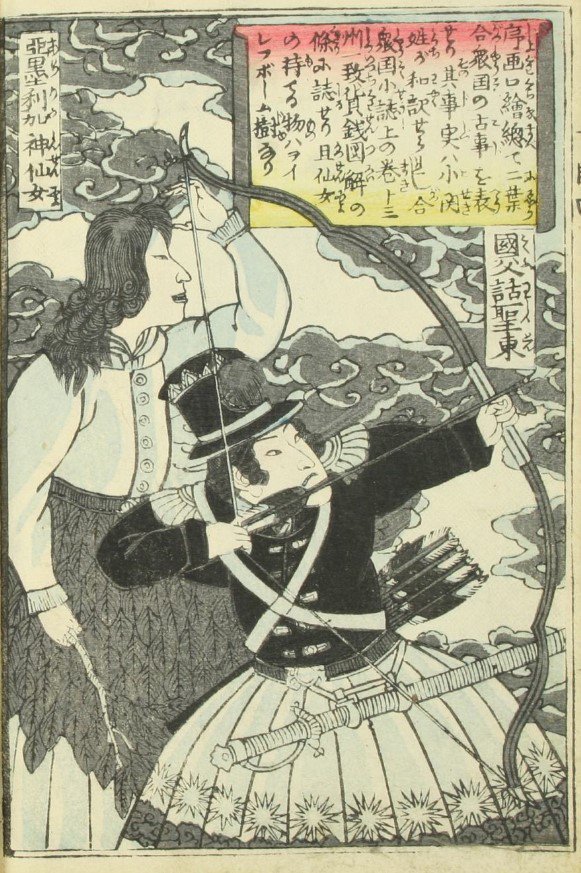

“George Washington (with bow and arrow) pictured alongside the Goddess of America”

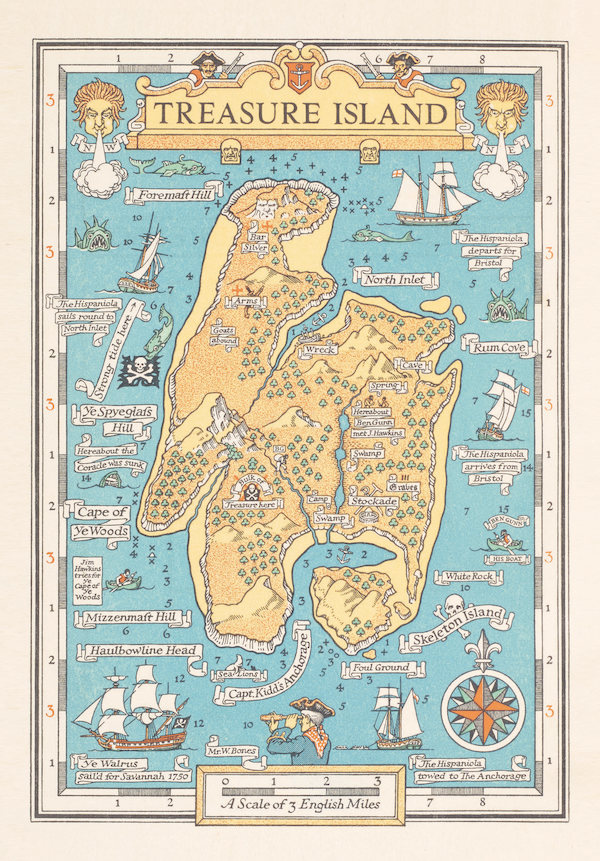

Though I’m American myself, I always learn the most about America when I look outside it. When I want to hear my homeland described or see it reflected, I seek out the perspective of anyone other than my fellow Americans. Given that I live in Korea, such perspectives aren’t hard to come by, and every day here I learn something new — real or imagined — about the United States. But Japan, the next country over to the east, has a longer and arguably richer tradition of America-describing. And judging by Osanaetoki Bankokubanashi (童絵解万国噺), an 1861 book by writer Kanagaki Robun and artist Utagawa Yoshitora, it certainly has a more fantastical one. “Here is George Washington (with bow and arrow) pictured alongside the Goddess of America,” writes historian of Japan Nick Kapur in a Twitter thread featuring selections from the book.

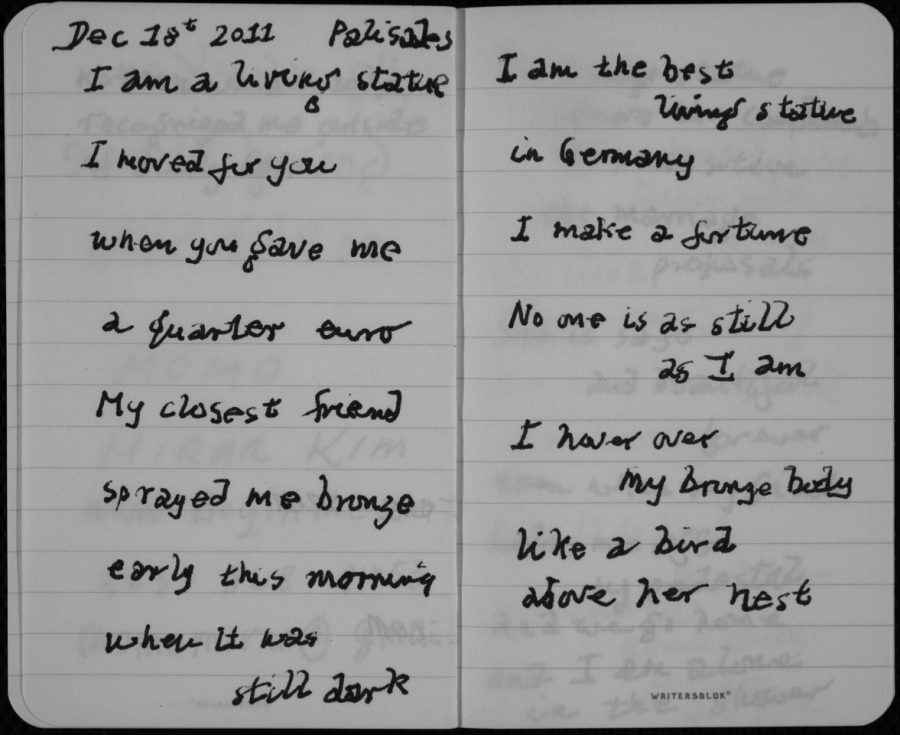

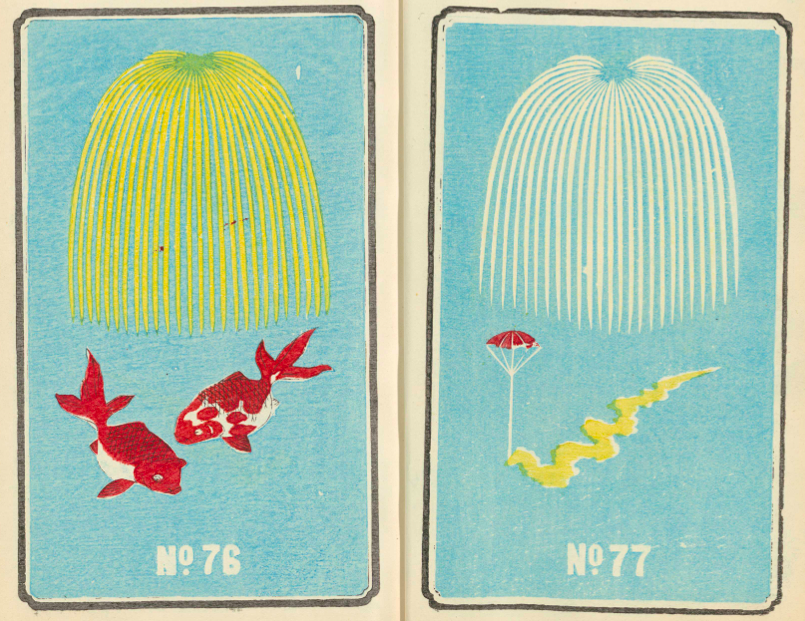

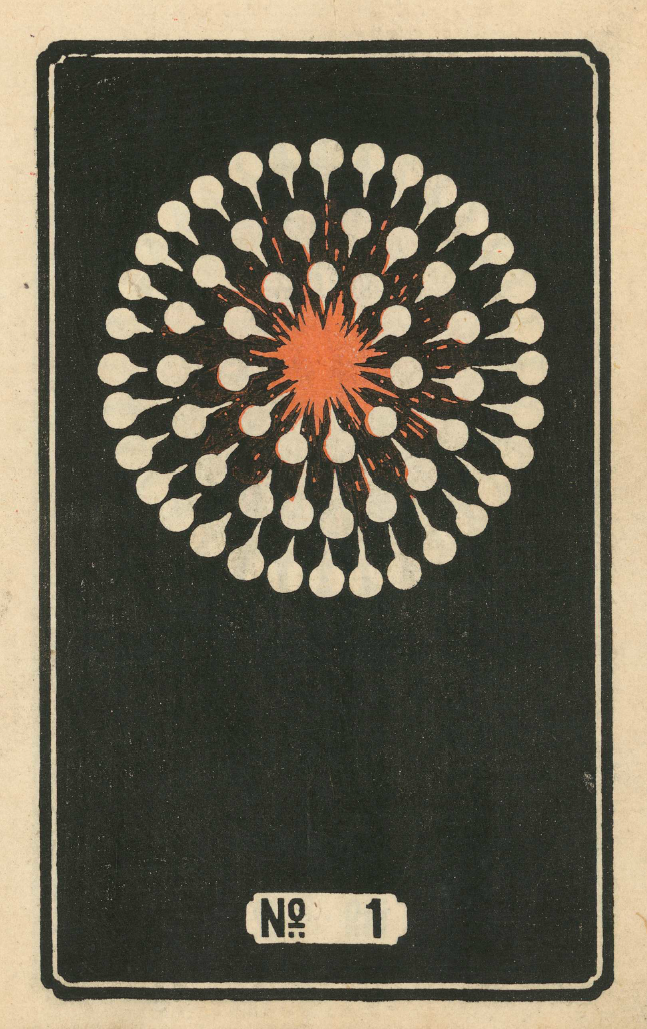

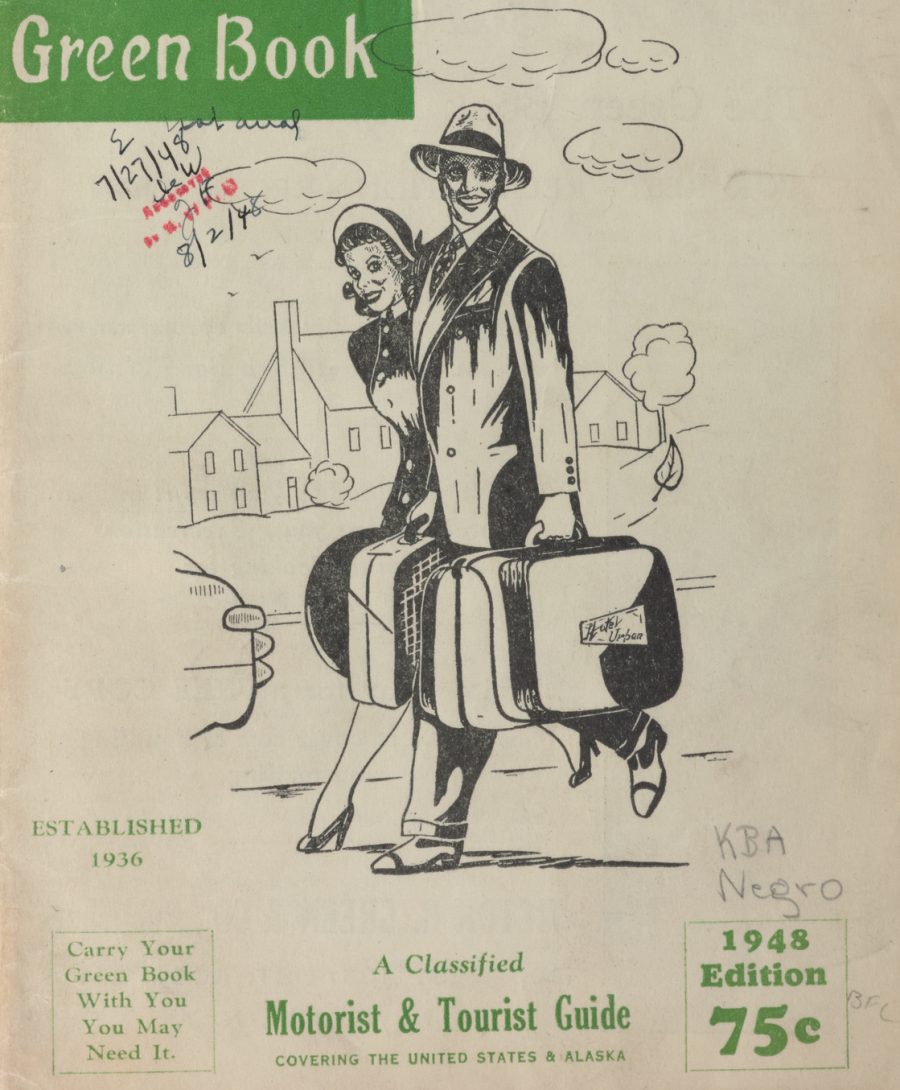

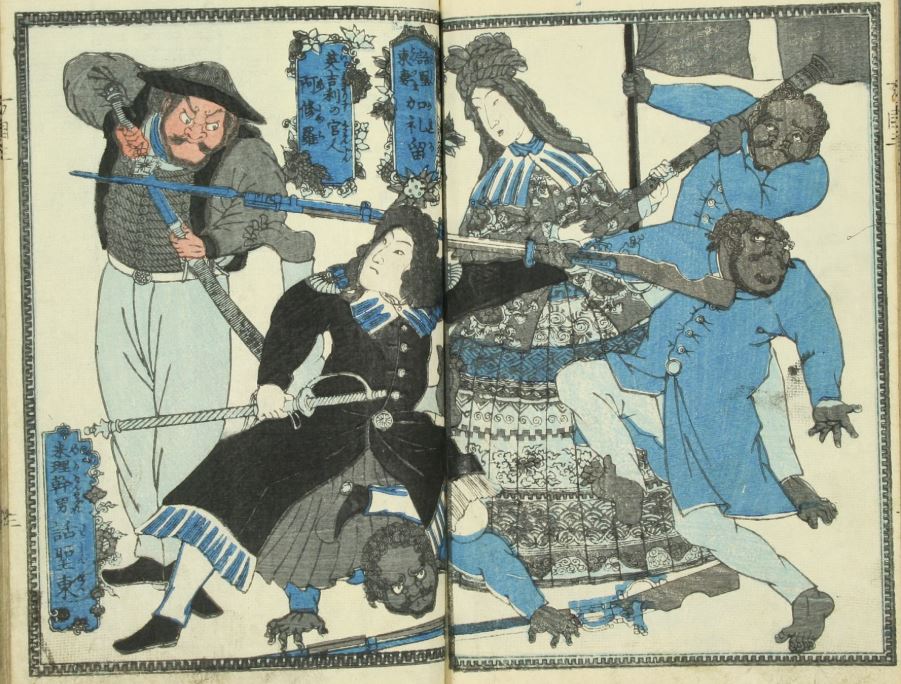

“George Washington defending his wife ‘Carol’ from a British official”

History does record Washington having practiced archery in his youth, among other popular sports of the day, and the image of the Goddess of America does look like a faintly Japanese version of Columbia, the historical female personification of the United States.

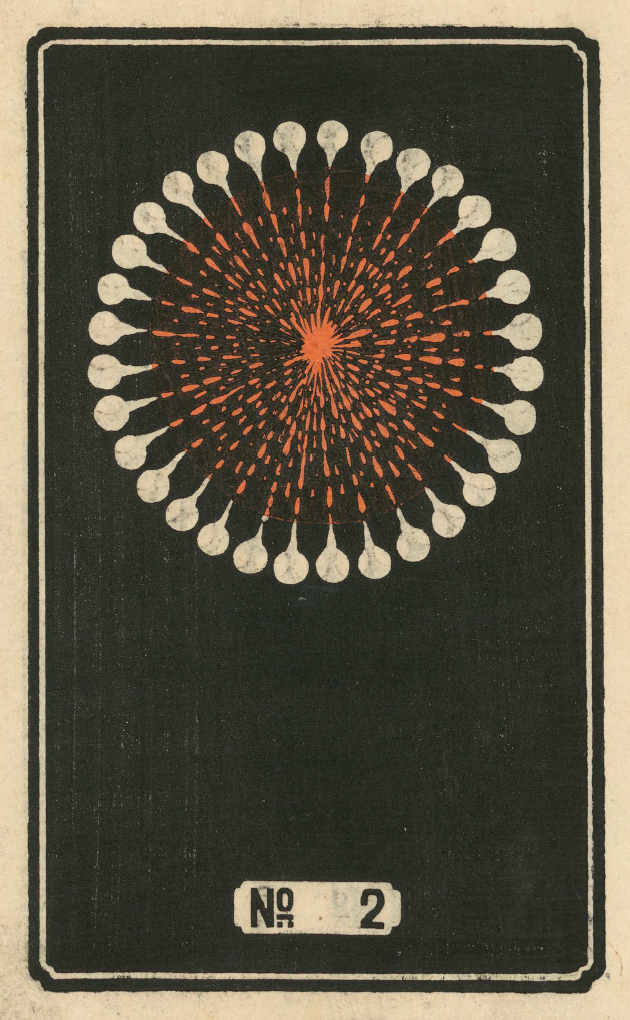

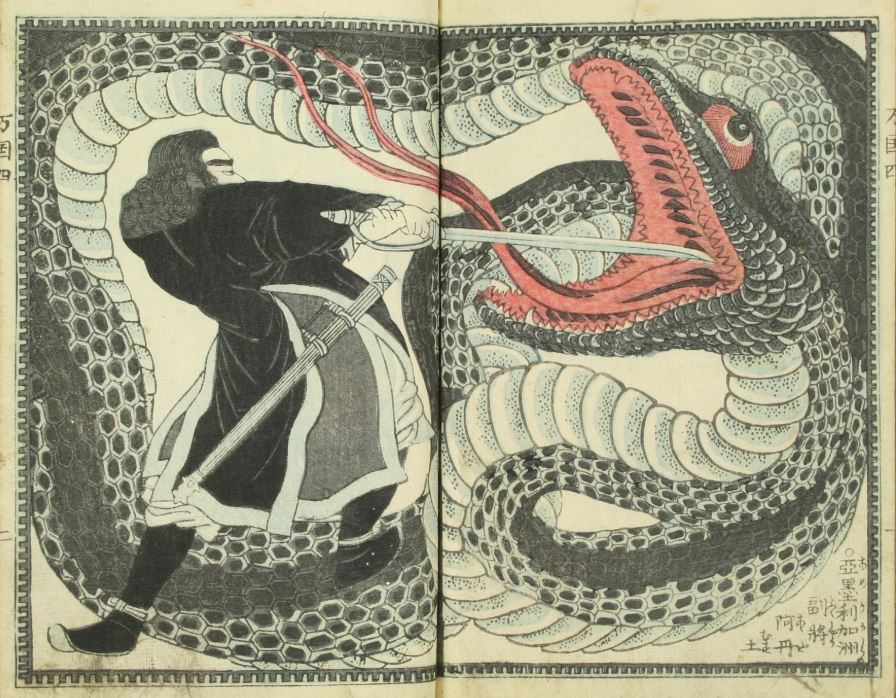

The next image Kaur posts shows Christopher Columbus reporting his discovery of America to Queen Isabella of Spain. “So far, kinda normal,” but then comes a bit of artistic license: a scene from the American Revolution in which we see “George Washington defending his wife ‘Carol’ from a British official named ‘Asura’ (same characters as the Buddhist deity).” Other illustrated events from early American history include “Washington’s “second-in-command” John Adams battling an enormous snake,” “the incredibly jacked Benjamin Franklin firing a cannon that he holds in his bare hands, while John Adams directs him where to fire,” and “George Washington straight-up punching a tiger.”

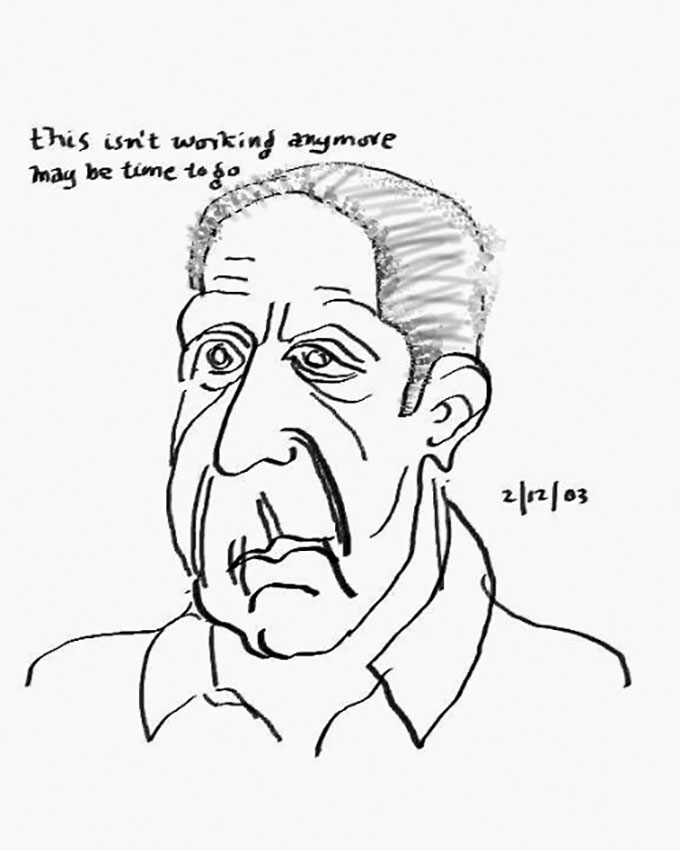

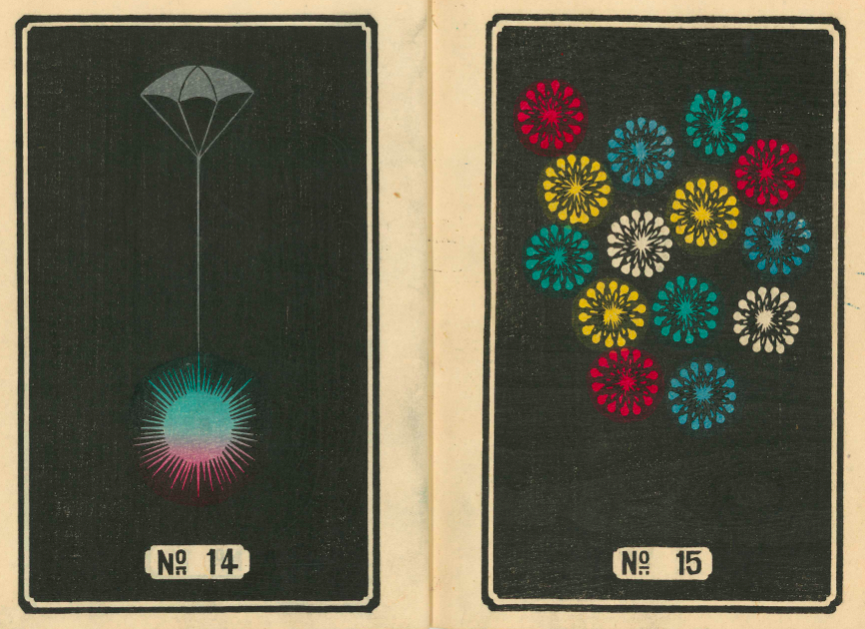

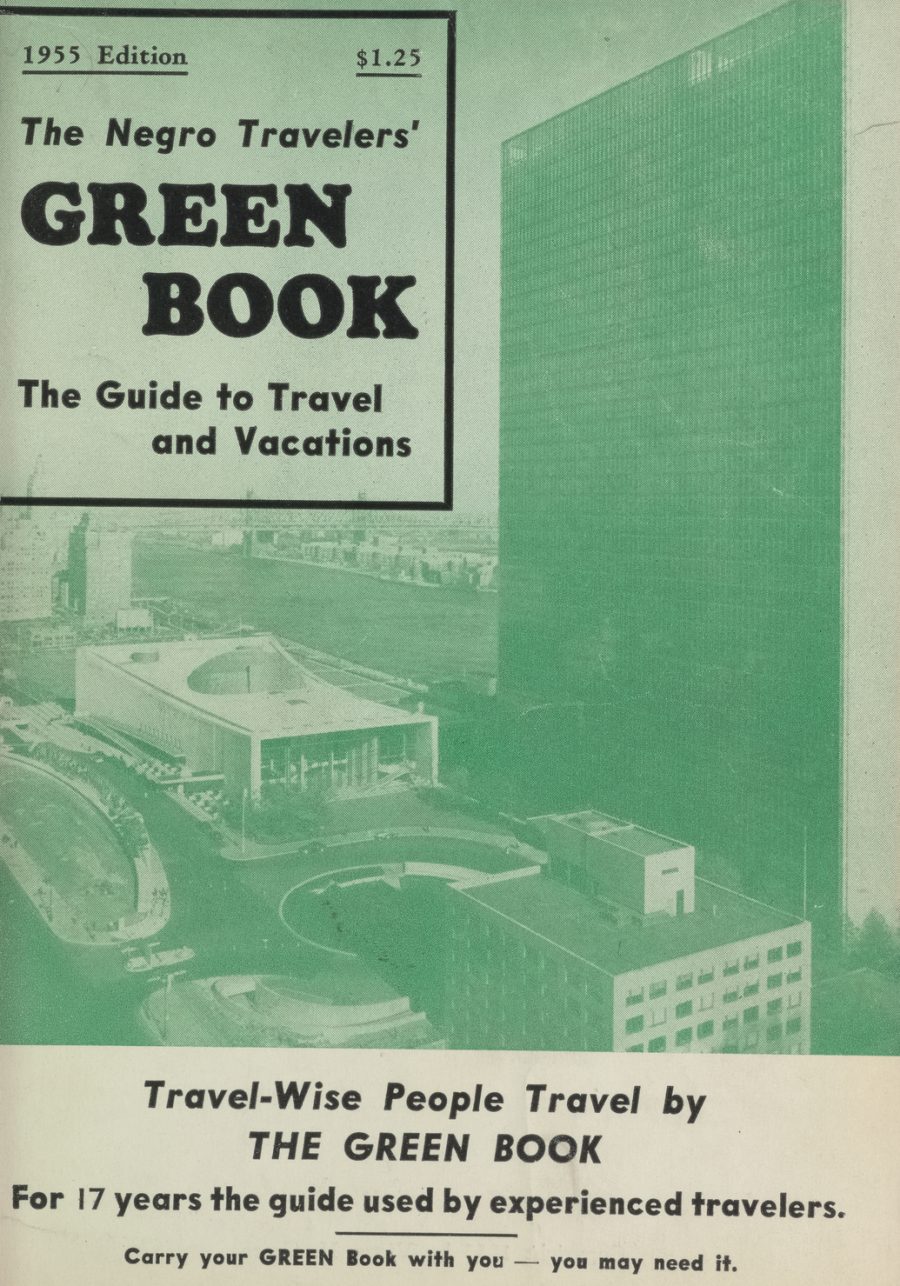

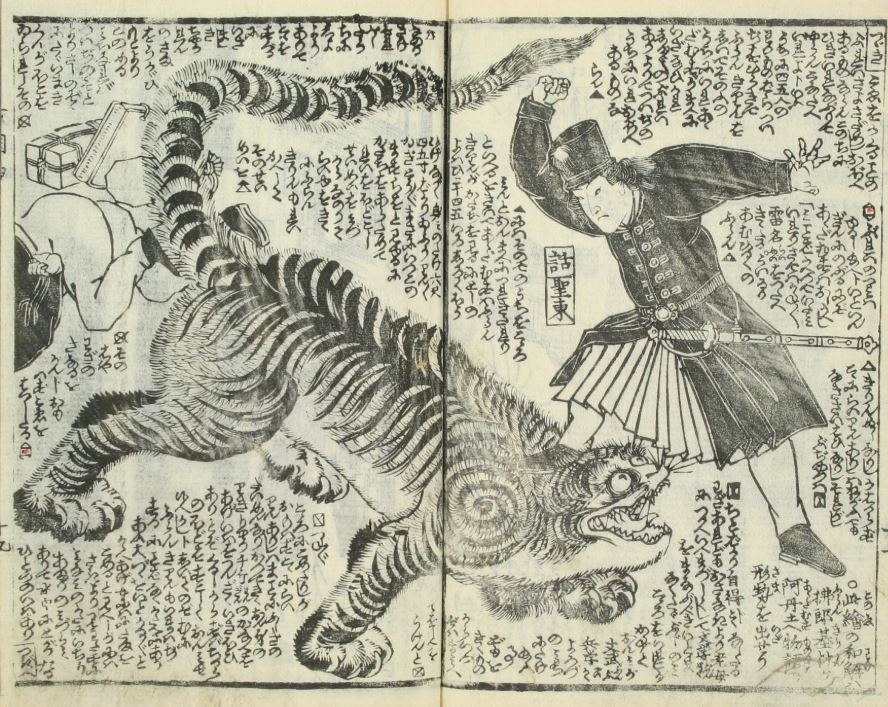

“George Washington straight-up punching a tiger”

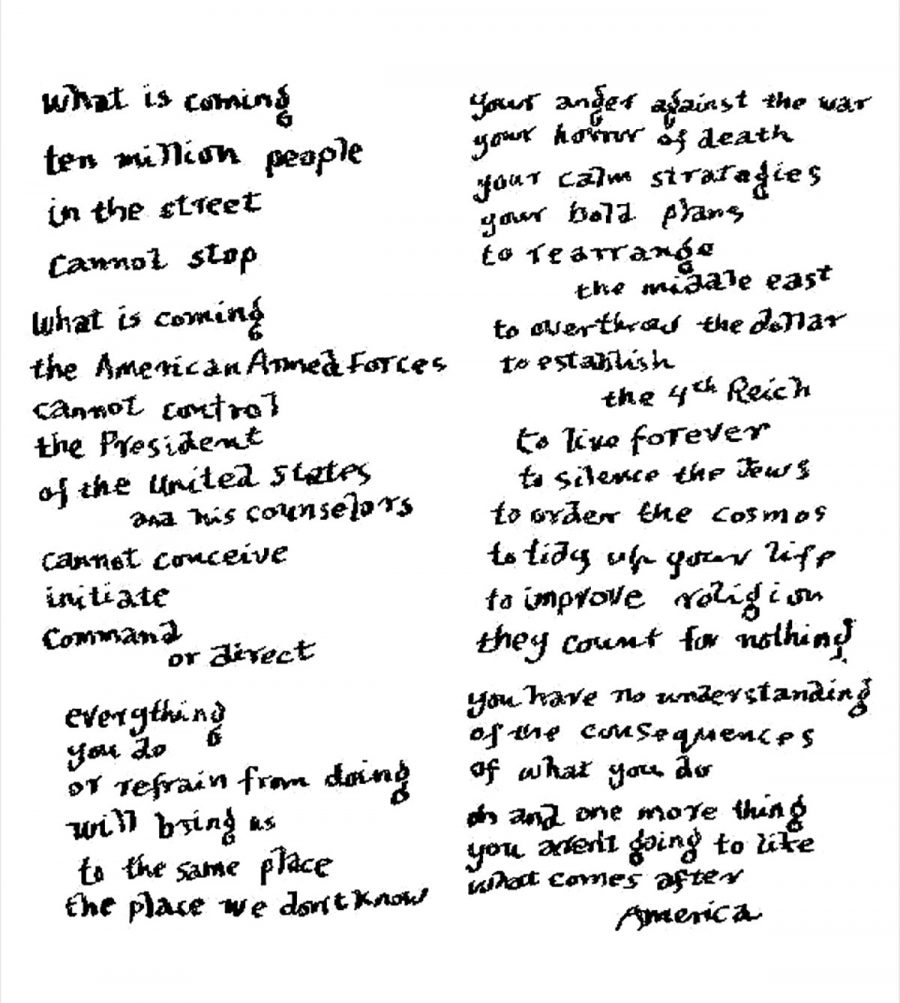

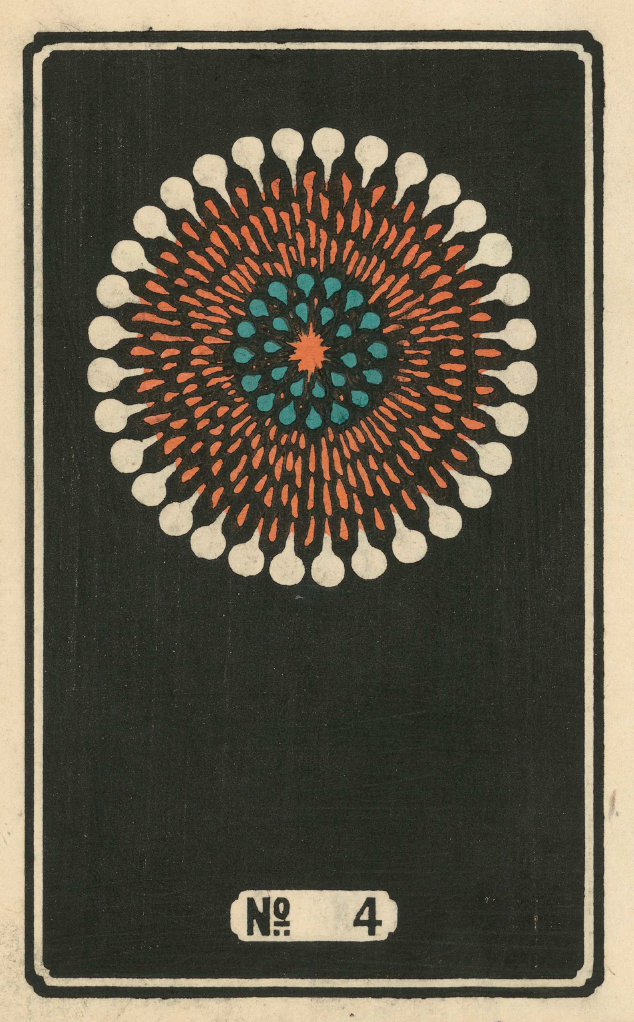

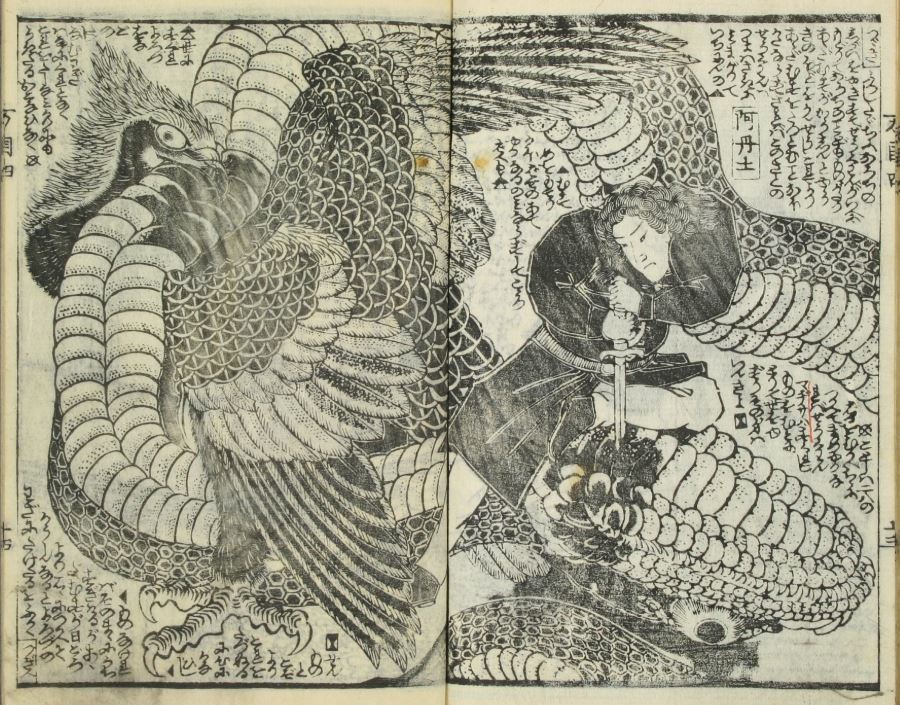

The founding of the United States, as Kanagaki and Utagawa saw it, seems to have required the defeat of many a fearsome beast, including a giant snake that eats Adams’ mother and against which Adams must then team up with an eagle to slay. What truth we can find here may be metaphorical in nature: even in the mid-19th century, the world still saw America as a vast, wild continent just waiting to enrich those brave and strong enough to subdue it. Global interest in the still-new republic also ran particularly high at that time, as evidenced by the popularity of publications like Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (which still offers an insightful outsider’s perspective on America), first published in 1835 and 1840.

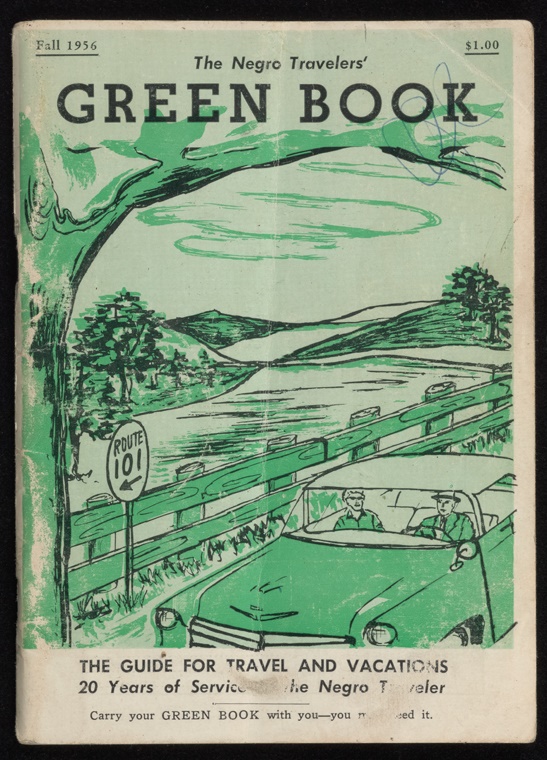

“Together, John Adams and the eagle kill the enormous snake that ate his Mom. The power of teamwork!!!”

Japan, long a closed country, had also begun to take a keen interest in the outside world: American Commodore Matthew Perry and his warships, filled with technology then unimaginable to the Japanese, had arrived in 1853 with an intent to open Japan’s ports to trade. In 1868 the Meiji Restoration would consolidate imperial rule in the country and open it to the world, but Osanaetoki Bankokubanashi, which you can read in its entirety in digitized form at Waseda Unversity’s web site, came out seven years before that. At that time, the likes of Kanagaki and Utagawa, relying on second-hand sources, could still thrill their countrymen — none of whom had any more direct experience of America than they did — with tales of the grotesque creatures, vile oppressors, heroic rebels, and guiding goddesses to be found just on the other side of the Pacific Ocean.

For more images, see Nick Kapur’s twitter stream here.

Related Content:

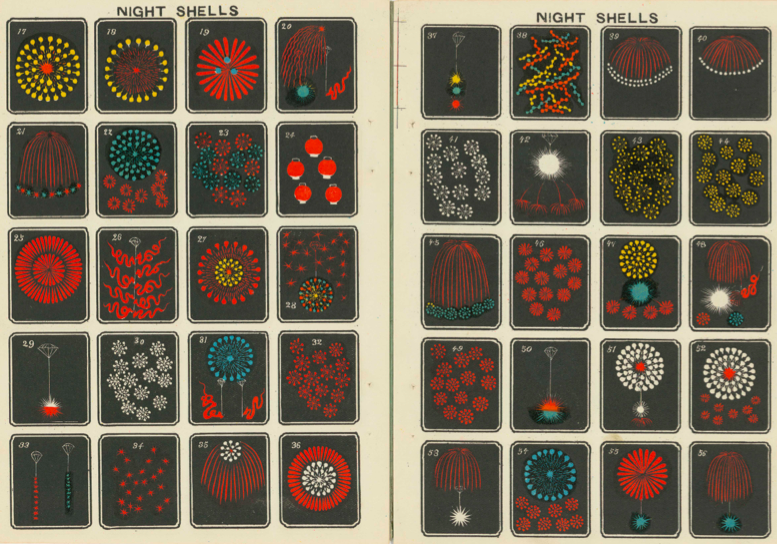

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.