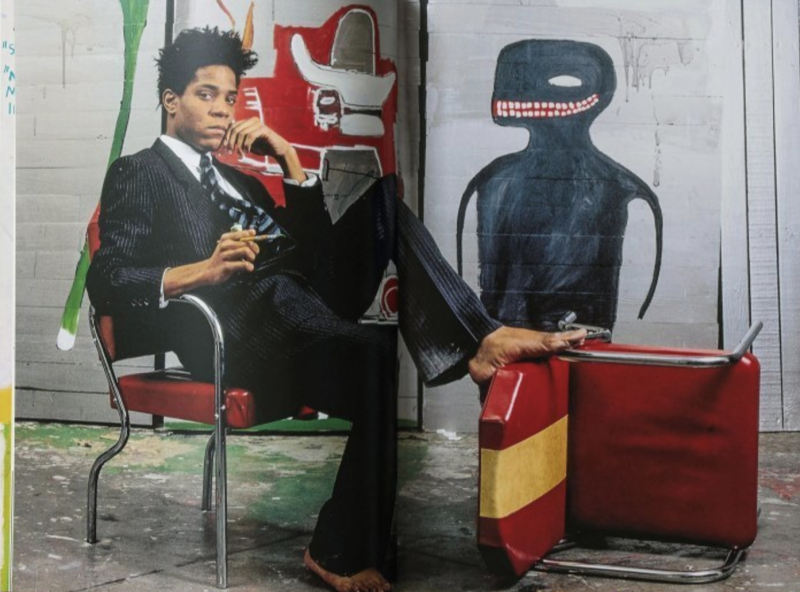

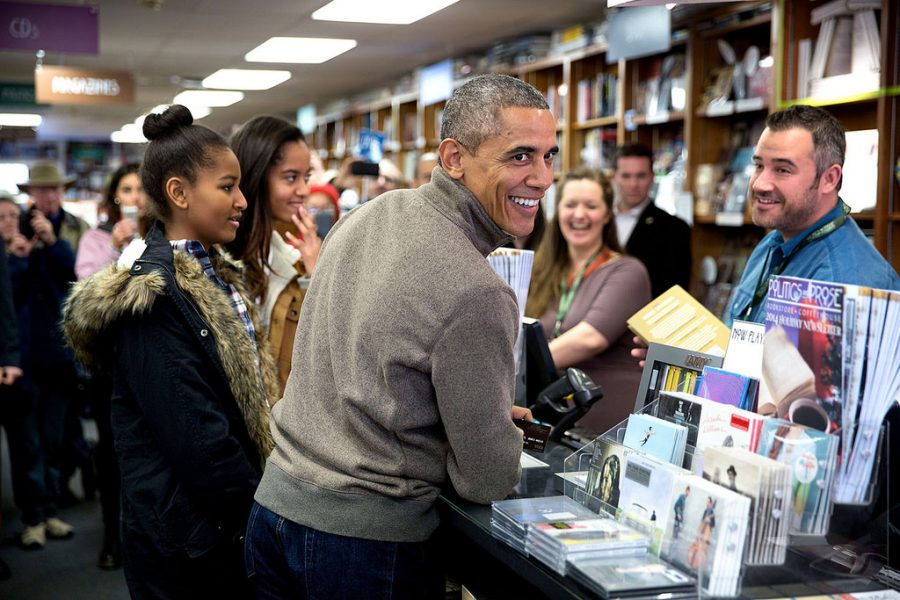

Photo by Pete Souza via obamawhitehouse.archive.gov

On Facebook this morning, President Obama wrote: “As 2018 draws to a close, I’m continuing a favorite tradition of mine and sharing my year-end lists. It gives me a moment to pause and reflect on the year through the books, movies, and music that I found most thought-provoking, inspiring, or just plain loved. It also gives me a chance to highlight talented authors, artists, and storytellers – some who are household names and others who you may not have heard of before. Here’s my best of 2018 list — I hope you enjoy reading, watching, and listening.” Note that you can hear all of the music on this Spotify playlist.

Books That Pres. Obama Read This Year:

Becoming by Michelle Obama (obviously my favorite!)

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The Broken Ladder: How Inequality Affects the Way We Think, Live, and Die by Keith Payne

Educated by Tara Westover

Factfulness by Hans Rosling

Futureface: A Family Mystery, an Epic Quest, and the Secret to Belonging by Alex Wagner

A Grain of Wheat by Ngugi wa Thiong’o

A House for Mr Biswas by V.S. Naipaul

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt

In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History by Mitch Landrieu

Long Walk to Freedom by Nelson Mandela

The New Geography of Jobs by Enrico Moretti

The Return by Hisham Matar

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

Warlight by Michael Ondaatje

Why Liberalism Failed by Patrick Deneen

The World As It Is by Ben Rhodes

Favorite Books of 2018:

American Prison by Shane Bauer

Arthur Ashe: A Life by Raymond Arsenault

Asymmetry by Lisa Halliday

Feel Free by Zadie Smith

Florida by Lauren Groff

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David W. Blight

Immigrant, Montana by Amitava Kumar

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden by Denis Johnson

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Max Tegmark

There There by Tommy Orange

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan

Favorite Movies of 2018:

Annihilation

Black Panther

BlacKkKlansman

Blindspotting

Burning

The Death of Stalin

Eighth Grade

If Beale Street Could Talk

Leave No Trace

Minding the Gap

The Rider

Roma

Shoplifters

Support the Girls

Won’t You Be My Neighbor

Favorite Songs of 2018

Apes••t by The Carters

Bad Bad News by Leon Bridges

Could’ve Been by H.E.R. (feat. Bryson Tiller)

Disco Yes by Tom Misch (feat. Poppy Ajudha)

Ekombe by Jupiter & Okwess

Every Time I Hear That Song by Brandi Carlile

Girl Goin’ Nowhere by Ashley McBryde

Historia De Un Amor by Tonina (feat. Javier Limón and Tali Rubinstein)

I Like It by Cardi B (feat. Bad Bunny and J Balvin)

Kevin’s Heart by J. Cole

King For A Day by Anderson East

Love Lies by Khalid & Normani

Make Me Feel by Janelle Monáe

Mary Don’t You Weep (Piano & A Microphone 1983 Version) by Prince

My Own Thing by Chance the Rapper (feat. Joey Purp)

Need a Little Time by Courtney Barnett

Nina Cried Power by Hozier (feat. Mavis Staples)

Nterini by Fatoumata Diawara

One Trick Ponies by Kurt Vile

Turnin’ Me Up by BJ the Chicago Kid

Wait by the River by Lord Huron

Wow Freestyle by Jay Rock (feat. Kendrick Lamar)

And in honor of one of the great jazz singers of all time, who died this year, a classic album: The Great American Songbook by Nancy Wilson

You can find all of these song neatly listed in a playlist here on Spotify.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The Books on Barack Obama’s Summer Reading List: Naipaul, Ondaatje & More

Barack Obama Shares a List of Enlightening Books Worth Reading

The 5 Books on President Obama’s 2016 Summer Reading List

A Free POTUS Summer Playlist: Pres. Obama Curates 39 Songs for a Summer Day