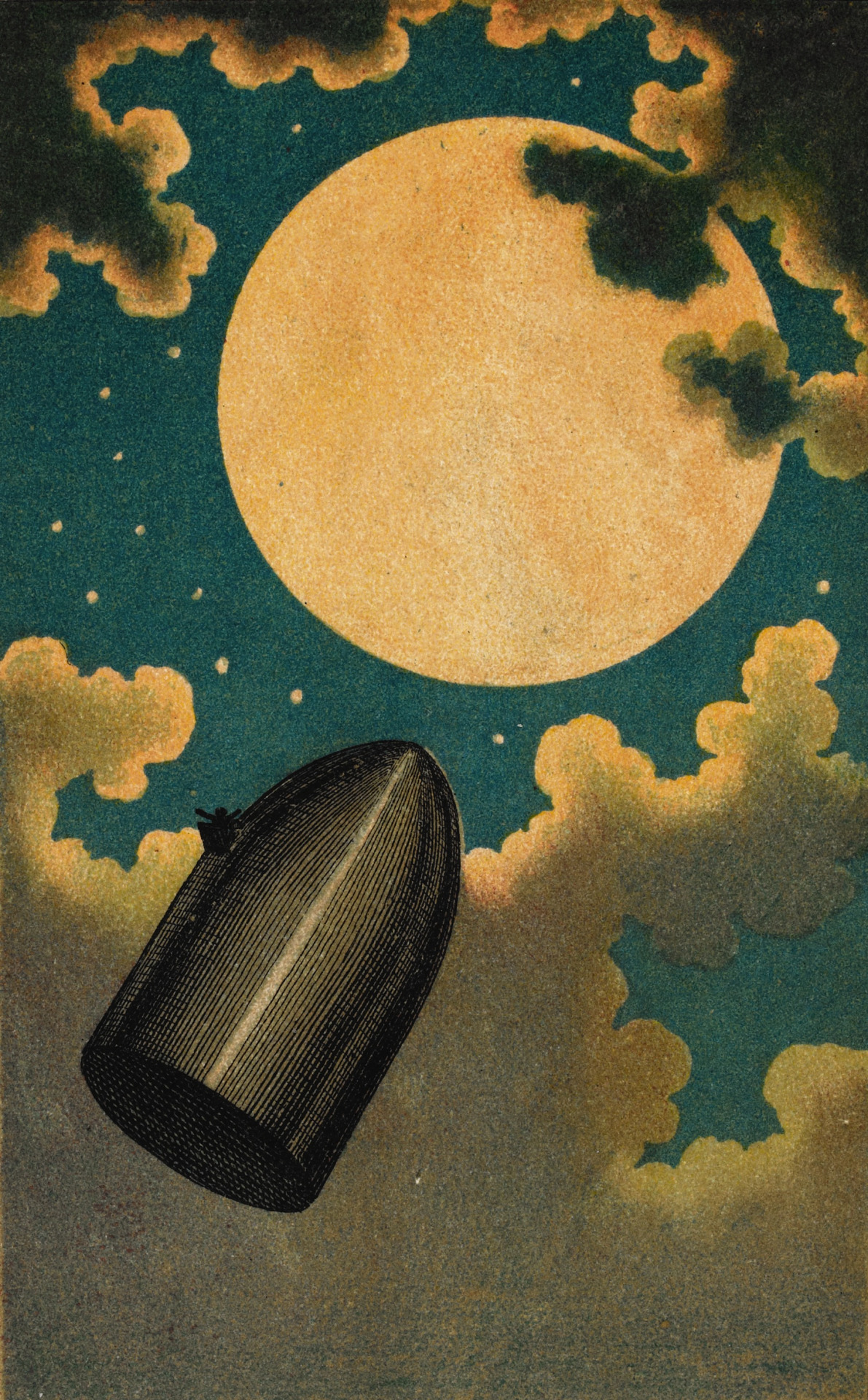

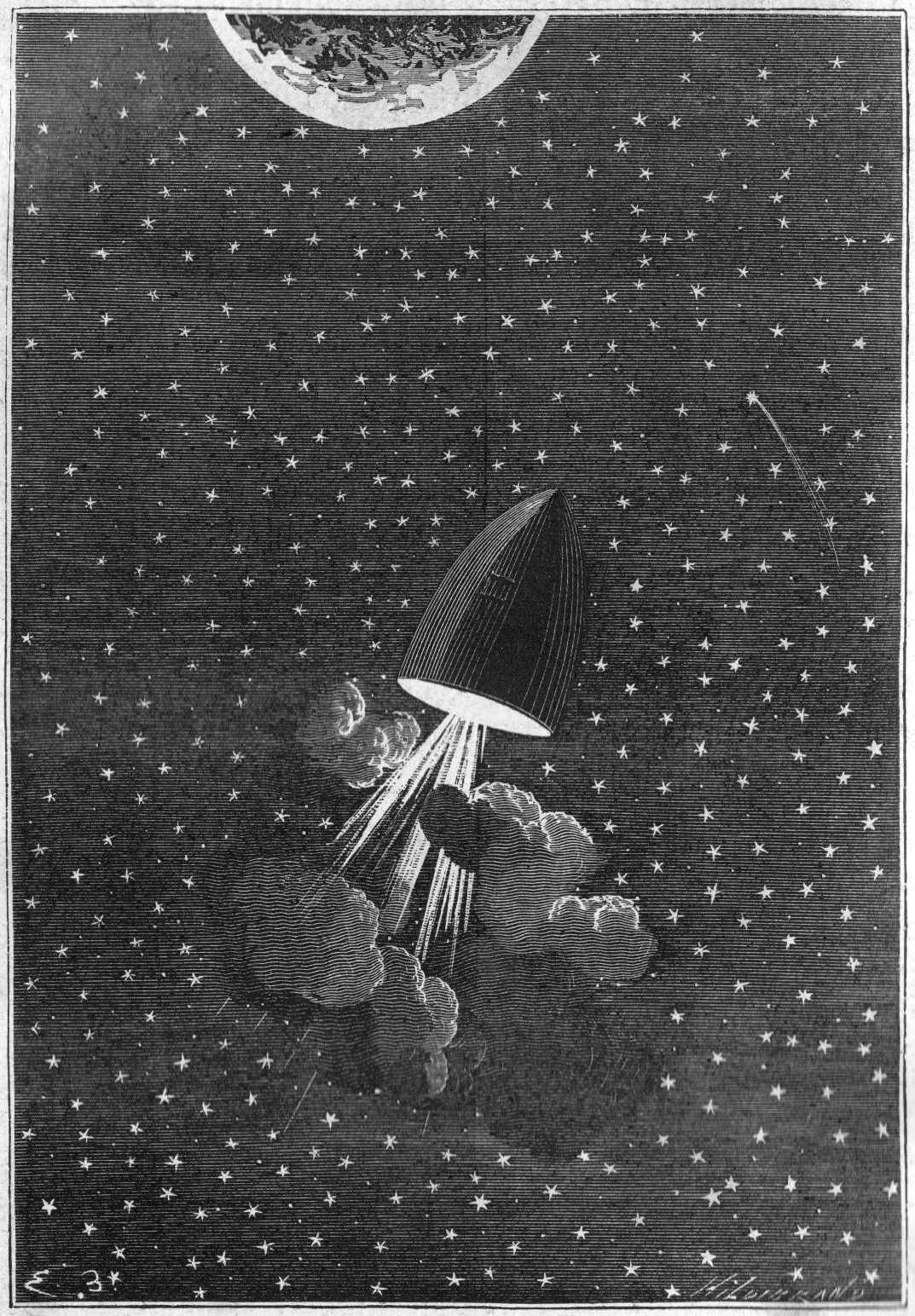

Hunter S. Thompson and Ray Bradbury would at first seem to have little in common, other than having made their livings by the pen. Or rather, both of them having developed as writers in the mid-20th century, by the typewriter–though Thompson famously shot his and a young Bradbury once had to rent one for ten cents per hour at UCLA’s library. In one nine-day rental in the early 1950s, Bradbury typed up Fahrenheit 451, still his best-known work and one whose central idea, that of a future society that methodically destroys all books, has stayed compelling almost 65 years after its first publication.

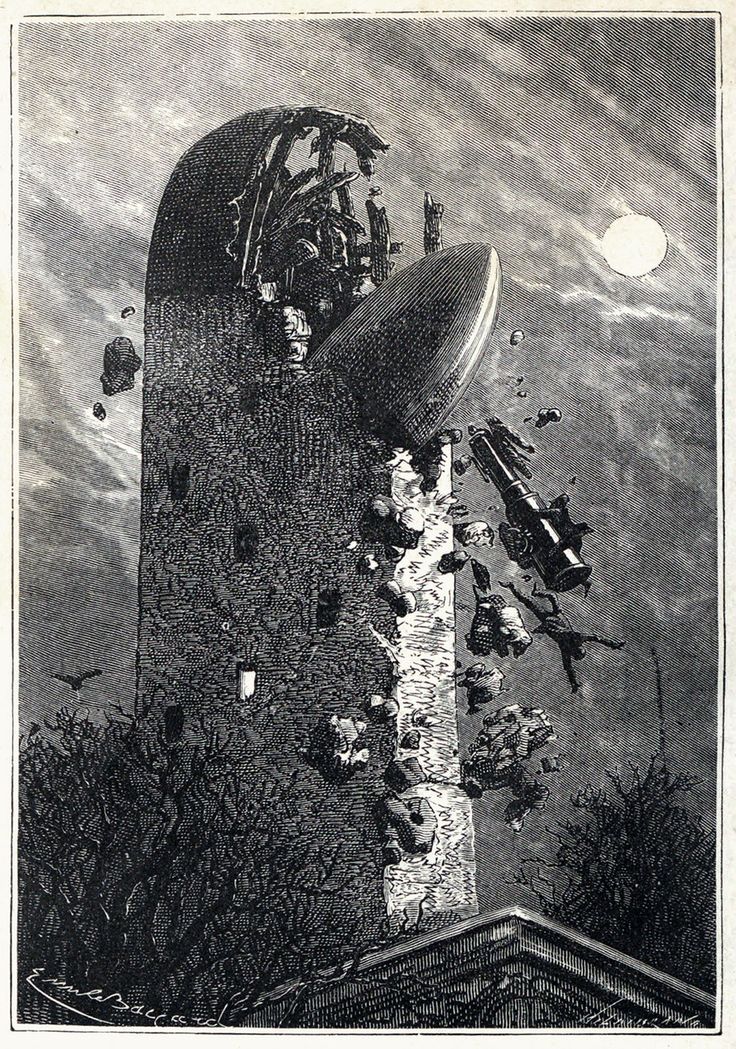

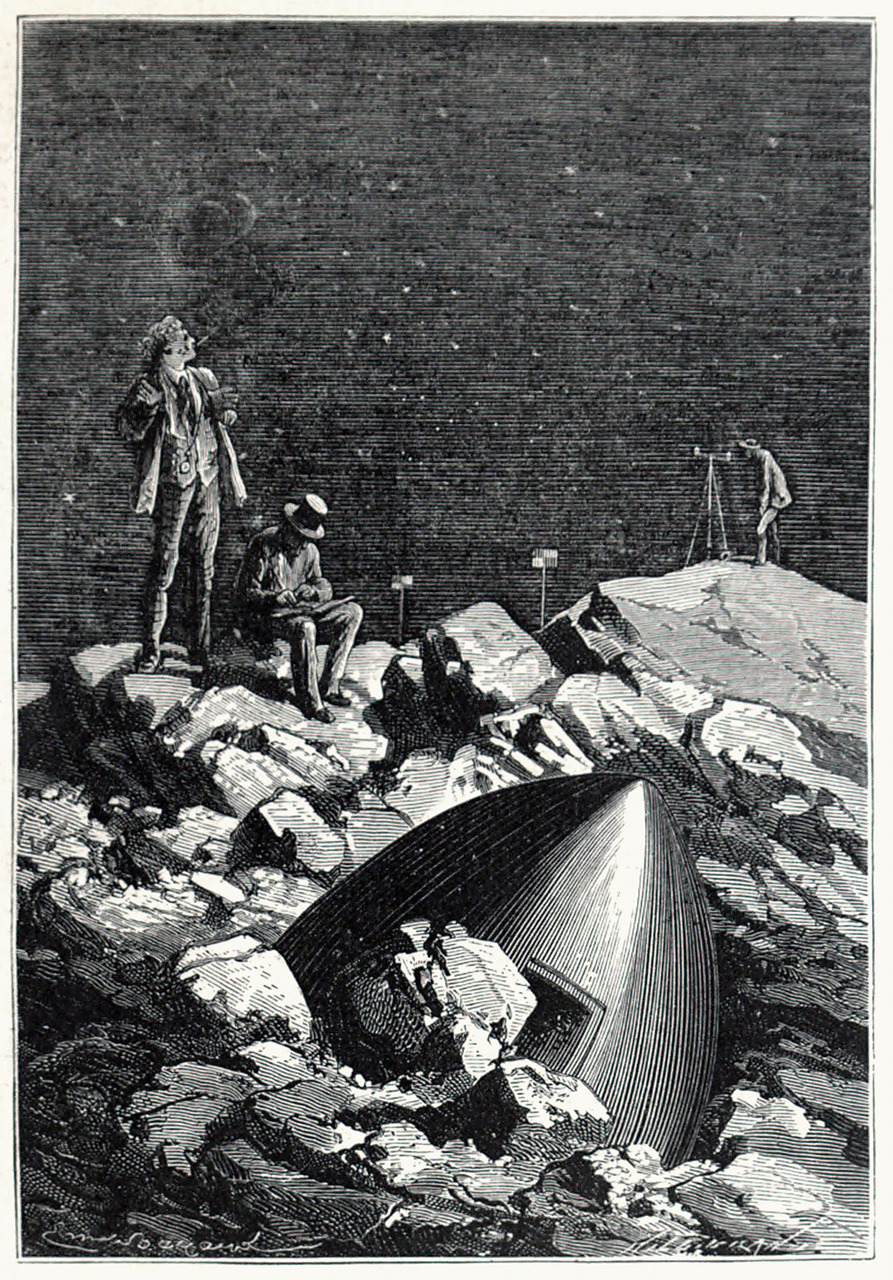

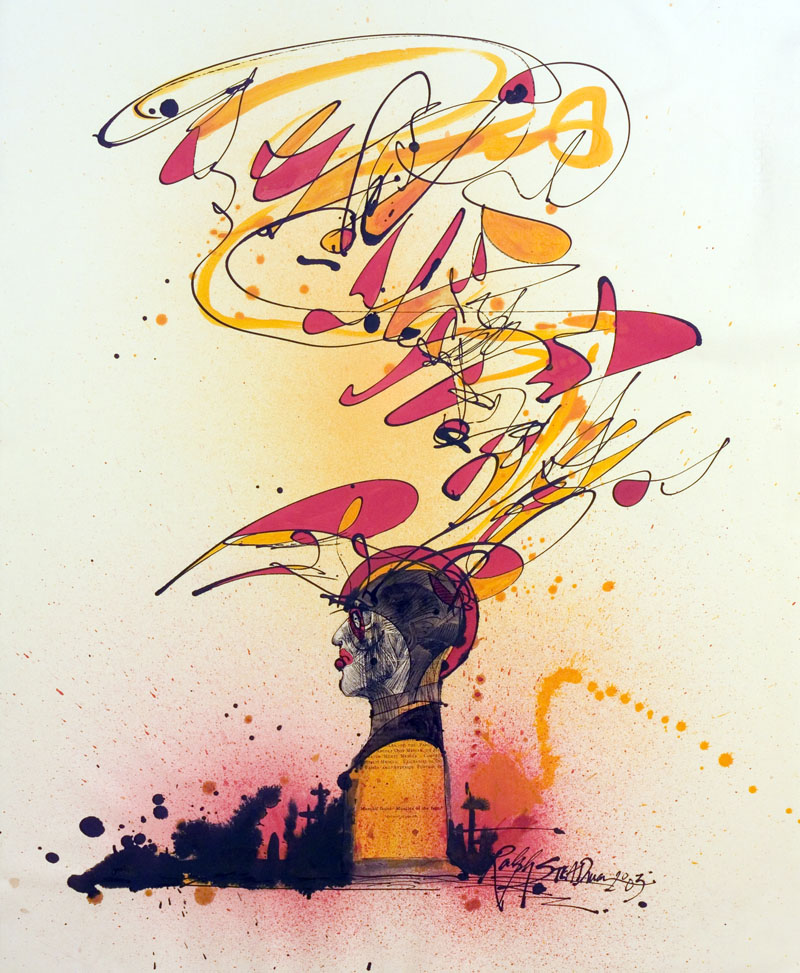

Thompson’s best-known work, 1971’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, deals in different kinds of frightening visions, some of them brought to illustrated life by the English artist Ralph Steadman. Thirty years later years later and with his name long since made by his collaboration with Thompson, Steadman would bring his talents to Bradbury’s dystopia. Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova quotes him describing the theme of Fahrenheit 451 as “vitally important.” According to Dangerous Minds’ Paul Gallagher, when Bradbury saw Steadman’s illustrations, commissioned for a limited edition of the book around its fiftieth anniversary, he said to the artist, “You’ve brought my book into the 21st century.”

Steadman repaid the compliment when he said that he considers Fahrenheit 451 “as important as 1984 and Animal Farm as real powerful social comment,” and he should know, having previously poured his artistic energies into a 1995 edition of George Orwell’s deceptively simple allegory of the Russian Revolution and its consequences. More than a few of us would no doubt love to see what Steadman could do with 1984 here in the 21st century, a time when we’ve hardly extinguished the societal dangers of which Orwell, or Bradbury, or indeed Thompson, tried, each in his distinctive literary way, to warn us. Book-burning may remain a fringe pursuit, but the fight against thought control in its infinite forms demands constant vigilance — and no small amount of imagination.

You can see more illustrations of Fahrenheit 451 at Brain Pickings and Dangerous Minds. Also, you can purchase used copies of the limited print edition online, though they seem quite rare at this point. Editions can be found on AbeBooks–for example here and here.

Related Content:

Gonzo Illustrator Ralph Steadman Draws the American Presidents, from Nixon to Trump

Ralph Steadman’s Surrealist Illustrations of George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1995)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.