No one would call this the golden era of teaching, not with school budgets getting slashed, state governors routinely scoring political points at teachers’ expense, and the federal government forcing schools to teach to the test. But if today’s teachers are feeling beleaguered, they can always look back to a set of historical “documents” for a little comfort. For decades, museums and publishers have showcased two lists — one from 1872 (above) and another from 1915 (below) — that highlight the rigorous rules and austere moral codes under which teachers once taught. You couldn’t drink or smoke. In women’s cases, you couldn’t date, marry, or frequent ice cream parlors. And, for men, getting a shave in a barber shop was strictly verboten.

But are these documents real?

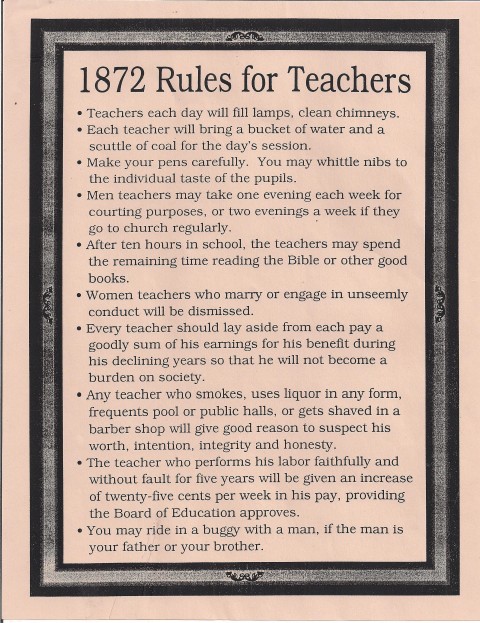

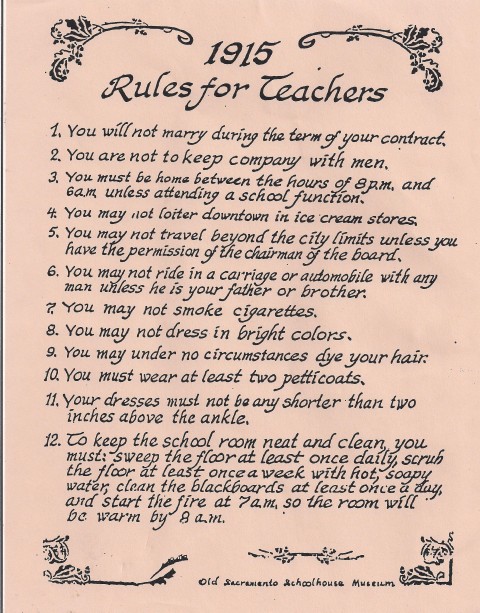

On its web site, the New Hampshire Historical Society writes that “the sources for these ‘rules’ are unknown; thus we cannot attest to their authenticity—only to their verisimilitude and charming quaintness.” “The rules from 1872 have been variously attributed to an 1872 posting in Monroe County, Iowa; to a one-room school in a small town in Maine; and to an unspecified Arizona schoolhouse. The 1915 rules are attributed to a Sacramento teachers’ contract and elsewhere to an unspecified 1915 magazine.” According to Snopes, the fact-checking web site, the 1872 list has been “displayed in numerous museums throughout North America,” over the past 50 years, “with each exhibitor claiming that it originated with their county or school district.” Heck, the lists even appeared in the venerated Washington Post not so long ago. Here are the rules:

Rules for Teachers — 1872

1. Teachers will fill the lamps and clean the chimney each day.

2. Each teacher will bring a bucket of water and a scuttle of coal for the day’s sessions.

3. Make your pens carefully. You may whittle nibs to the individual tastes of the pupils.

4. Men teachers may take one evening each week for courting purposes, or two evenings a week if they go to church regularly.

5. After ten hours in school, the teachers may spend the remaining time reading the Bible or other good books.

6. Women teachers who marry or engage in improper conduct will be dismissed.

7. Every teacher should lay aside from each day’s pay a goodly sum of his earnings. He should use his savings during his retirement years so that he will not become a burden on society.

8. Any teacher who smokes, uses liquor in any form, visits pool halls or public halls, or gets shaved in a barber shop, will give good reasons for people to suspect his worth, intentions, and honesty.

9. The teacher who performs his labor faithfully and without fault for five years will be given an increase of twenty-five cents per week in his pay.

Rules for Teachers — 1915

1. You will not marry during the term of your contract.

2. You are not to keep company with men.

3. You must be home between the hours of 8 PM and 6 AM unless attending a school function.

4. You may not loiter downtown in ice cream stores.

5. You may not travel beyond the city limits unless you have the permission of the chairman of the board.

6. You may not ride in a carriage or automobile with any man except your father or brother.

7. You may not smoke cigarettes.

8. You may not dress in bright colors.

9. You may under no circumstances dye your hair.

10. You must wear at least two petticoats.

11. Your dresses may not be any shorter than two inches above the ankles.

12. To keep the classroom neat and clean you must sweep the floor at least once a day, scrub the floor at least once a week with hot, soapy water, clean the blackboards at least once a day, and start the fire at 7 AM to have the school warm by 8 AM.

via Peter Kaufman, mastermind of the Intelligent Channel on YouTube.

Related Content:

200 Free Kids Educational Resources: Video Lessons, Apps, Books, Websites & More

750 Free Online Courses from Top Universities