What with all that has, over the past 36 years, grown out of it — sequels, prequels, toys, novels, radio productions, video games, LEGO sets, LEGO set-themed video games, conventions, PhD theses, and an entire universe of content besides — we can only with difficulty remember how Star Wars began. The whole thing came preceded by the promise of nothing grander, more profound, or minutia-packed than a rollicking mythic space opera, and above, we have a reminder of that fact in the form of the first film’s original teaser trailer. “Somewhere in space, this may all be happening right now,” intones its faintly haunting narrator. “The story of a boy, a girl, and a universe. It’s a big, sprawling saga of rebellion and romance. It’s a spectacle light-years ahead of its time. It’s an epic of heroes and villains and aliens from a thousand worlds. Star Wars: a billion years in the making… and it’s coming to your galaxy this summer.”

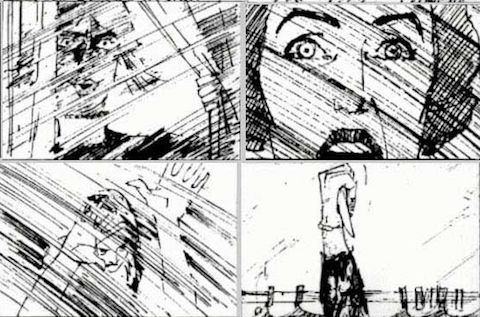

Since nothing suits Star Wars quite like completism, we’ve also included the teasers for the rest of the original trilogy: The Empire Strikes Back, just above, and Return of the Jedi, below. “In the continuation of the Star Wars saga,” booms the more traditional voice-over about the second film over hand-drawn imagery of its scenes, “the Empire strikes back, and Luke, Han, and Leia must confront its awesome might. In the course of the odyssey, they travel with their faithful friends, droids and wookiees, to exotic worlds where they meet new alien creatures and evil machines, culminating in an awesome confrontation between Luke Skywalker and the master of the dark side of the Force, Darth Vader.” By 1983, the time of the third picture, then titled Revenge of the Jedi, the series had amassed such a following that the narrator needed only rattle off the familiar heroes, villains, and various space critters we’d encounter once again.

Related Content:

Star Wars Uncut: The Epic Fan Film

Star Wars Gets Dubbed into Navajo: a Fun Way to Preserve and Teach a Fading Language

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.