Click images for larger versions

Film buffs and scholars have a new cache at their fingertips. The Media History Digital Library has made hundreds of thousands of pages of film and broadcasting history available in a searchable digital archive they’ve called Lantern, an open access, interactive library.

With help from the University of Wisconsin, Madison Department of Communication Arts, MHDL made their entire collection of Business Screen, The Hollywood Reporter, Photoplay and Variety—among other magazines—available for text searches for the first time.

In 2011 a group of film scholars developed MHDL, an updated resource for historians used to reading through microfilm archives of cinema and broadcast journals. At the time, their archive was a goldmine, pulling together the bounty of printed material chronicling the film industry. Now they’ve made it better, with more refined search, filtering and sorting tools. Plus you can download images and texts.

It may have been a rite of passage for film students to sequester themselves in a dark library carrel and scroll through microfiche reels of Moving Picture World, an influential trade journal until 1927, but Lantern brings venerable movie magazines dating up to the early ’70s into the light of day where anyone can access the images and articles of major trade and fan magazines, free of charge.

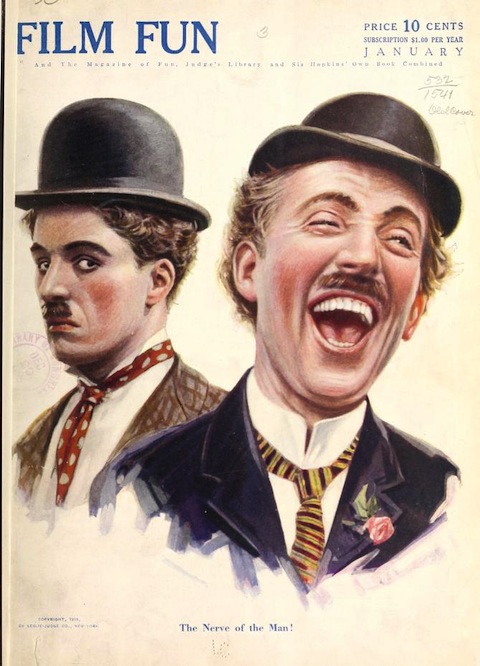

An early on-set chat rag, Film Fun, a magazine about “the happy side of the movies,” brought readers “intimate gossip of the profession told by the actors and actresses ‘between the reels.’” The images are gorgeous.

In the twenties a new amateur movie making industry thrived, with equipment and even tour packages available for buffs who wanted to tour exotic locales like Cuba with cameras and learn to shoot and preserve 16 mm motion pictures. A boom in DIY film magazines like Amateur Movie Makers targeted the early adopters.

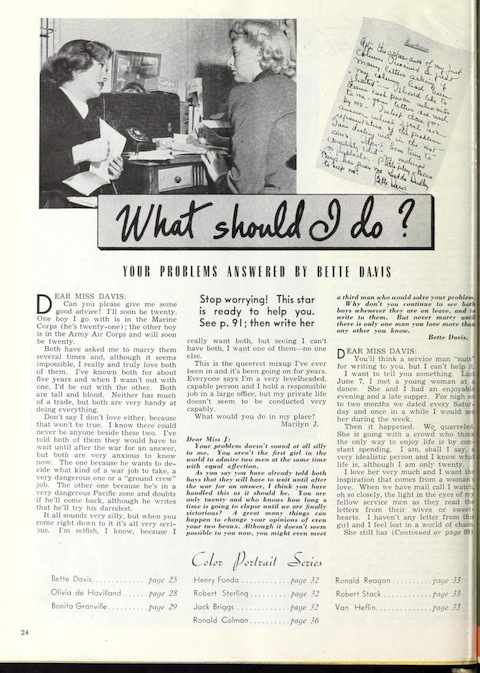

And lest we think that pulp celebrity mags like People and Us are lower brow than those of yesteryear, we should think again. I’m not sure about you, but I’m not sure four-times-married Bette Davis makes the best love advice columnist. But apparently Photoplay magazine did.

Related Content:

Three Great Films Starring Charlie Chaplin, the True Icon of Silent Comedy

How Brewster Kahle and the Internet Archive Will Preserve the Infinite Information on the Web

Kate Rix writes about education and digital media. Visit her website and follow her on Twitter.