Most of us know The War of the Worlds because of Orson Welles’ slightly-too-realistic radio adaptation, first broadcast on Halloween 1938. But its source material, H.G. Wells’ 1898 science-fiction novel, still fires up the imagination. Its many adaptations since have taken the form of comic books, video games, television series, and more besides. Several films have used The War of the Worlds as their basis, including a high-profile one in 2005 directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Tom Cruise, and more than half a century before that, George Pal’s first 1953 adaptation in all its Technicolor glory.

In recent years materials have surfaced showing us the midcentury War of the Worlds picture that could have been, one featuring the stop-motion creature-creation of Ray Harryhausen.

“Well before CGI technology beamed extraterrestrials onto the big screen, stop-motion animation master Harryhausen brought to life Wells’ vision of a slimy Martian with enormous bulging eyes, a slobbering beaked mouth and ‘Gorgon groups of tentacles’ in a 16 mm test reel,” writes Den of Geek’s Elizabeth Rayne.

“The result is something that looks like a twisted mashup of a Muppet and an octopus.” Harryhausen had long dreamed of bringing The War of the Worlds to the big screen, and anyone who has seen Harryhausen’s work of the 1950s and 60s, as it appears in such films as The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts, knows that he was surely the man for this job. He certainly had the right spirit: as his own words put it at the beginning of the test-footage clip, “ANY imaginative creature or thing can be built and animated convincingly.”

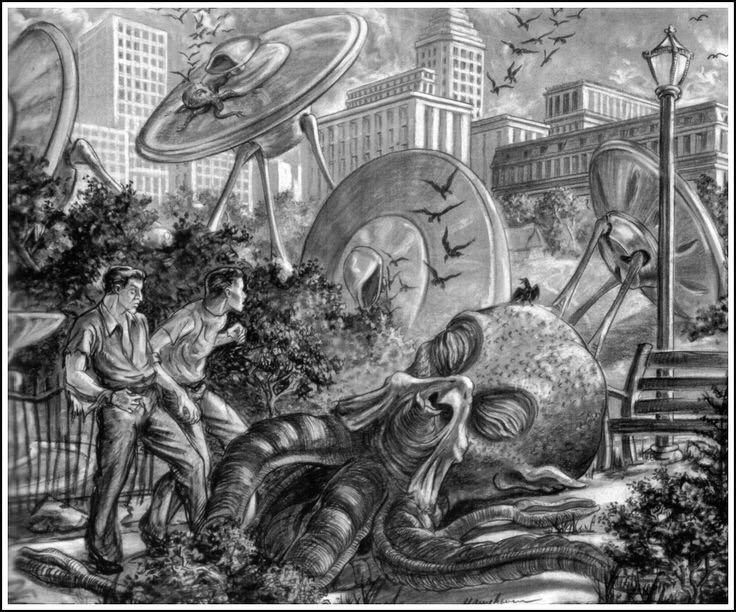

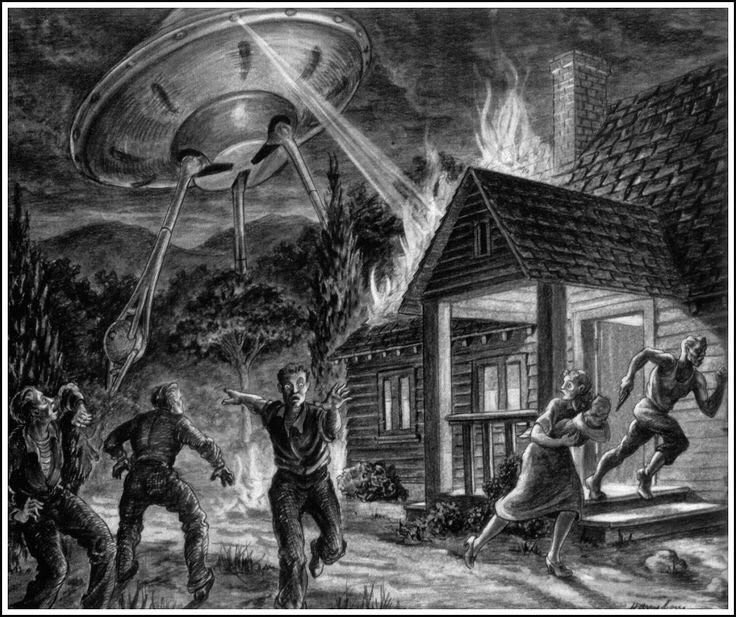

“I actually built a Martian based on H.G. Wells description,” Harryhausen says in the interview clip above. “He described the creature that came from the space ship a sort of an octopus-like type of creature.” Harryhausen’s also presented his vision with included sketches of the tripod invaders laying waste to America both urban and rural. “I took it all around Hollywood,” he says, but alas, it never quite convinced those who kept the gates of the Industry in the 1940s.

“We couldn’t raise money. People weren’t that interested in science fiction at that time.” Times have changed; the public has long since developed an unquenchable appetite for stories of human beings and advanced, hostile space invaders locked in mortal combat. But now such a spectacle would almost certainly be realized with the intensive use of computer-generated imagery, a technology impressive in its own way, but one that may never equal the personality, physicality, and sheer creepiness of the creatures that Ray Harryhausen brought painstakingly to life, one frame at a time, all by hand.

Related Content:

The Very First Illustrations of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1897)

Edward Gorey Illustrates H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in His Inimitable Gothic Style (1960)

Hear Orson Welles’ Iconic War of the Worlds Broadcast (1938)

The Mascot, a Pioneering Stop Animation Film by Wladyslaw Starewicz

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.