If you haven’t played video games in a long time, you might feel a certain trepidation at the idea of picking them up again. So rapidly have they evolved in the 21st century that they now resemble less the electronic entertainments we once knew than full-fledged alternate realities. The sudden rise of the word immersive to describe the very kind of experiences they constitute says it all. If you enter one of the elaborate worlds built by modern video game developers, how do you extract yourself again — especially if the world is one as fascinating as ancient Greece, recreated elaborately and to great acclaim in this year’s Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey?

Even non-gamers will have heard of the Assassin’s Creed series, which began in 2007 and has had a major release (in addition to as many minor ones, as well as ventures into other media) each and every year since. It has previously taken as its settings such chapters of human history as Victorian England, the Italian Renaissance, and Ptolemaic Egypt, but its latest installment goes farther back in time than any other. Players will find themselves dropped “into 431 BCE in Ancient Greece, at the start of the Peloponnesian War predominantly fought between Athens and Sparta,” writes Hyperallergic’s Zachary Small. “For a video game that includes bloody mercenaries, extraterrestrial beings, and time travel, Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey is shockingly faithful to our contemporary historical understanding of what Ancient Greece looked like during its golden age.”

The very idea might startle those of us who remember the settings of video games as perfunctory at best, mere backgrounds to run past while we blasted enemies, jumped from platform to platform, and collected power-ups. Assassin’s Creed takes its historical world-building so seriously that the previous game in the series, Assassin’s Creed: Origins, even came with an “educational mode” that allowed players to freely explore ancient Egypt — a far cry indeed from the dull, purpose-built educational games of yore. But Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey takes it to another level, incorporating seemingly everything known about ancient Greece at the time of its development. “The Ubisoft development team behind the game even hired a historical advisor to help them recreate a meticulous version of the Ancient World,” writes Small, “one that includes hundreds of polychromatic statues, temples, and tombs.”

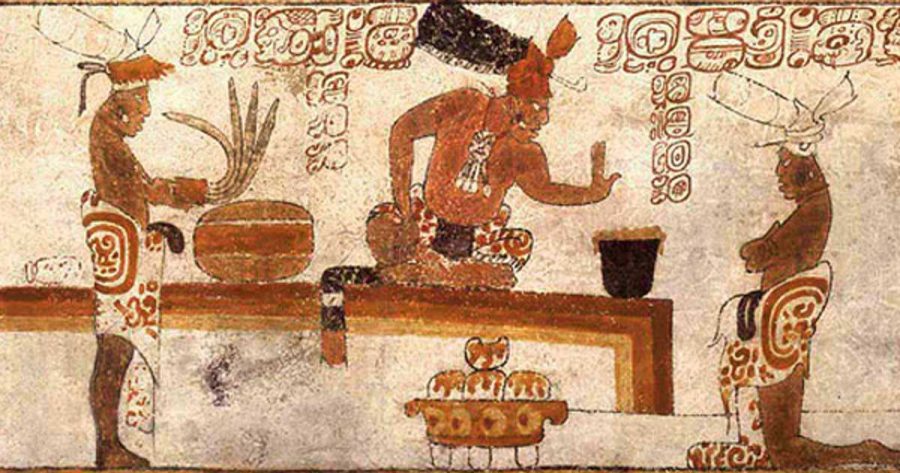

Yes, that means the game’s vision of ancient Greece includes plenty of sculpture made, as we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture, with not just with raw marble but brightly colored paint as well. The sheer amount of history and lore incorporated into the Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey experience has even inspired a discussion among experts on Twitter using the hashtag #ACademicOdyssey.

Though nobody claims that the game recreates ancient Greece perfectly in every detail — even apart from the gaps in human knowledge of the period, the developers seem to have had to cut a corner here and there to meet the series’ famously demanding release schedule — it succeeds in ways that no one Hellenically inclined, professionally or otherwise, had dared hope before. “I have played about 5 minutes of the game and I’m ready to cry from joy,” tweeted classicist Christine Plastow, a sentiment one can hardly imagine any academic expressing about, say, Golden Axe.

via Ars Technica/Hyperallergic

Related Content:

How Ancient Greek Statues Really Looked: Research Reveals their Bold, Bright Colors and Patterns

Watch Art on Ancient Greek Vases Come to Life with 21st Century Animation

Ancient Greek Punishments: The Retro Video Game

Concepts of the Hero in Greek Civilization (A Free Harvard Course)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.