(Click image to enlarge)

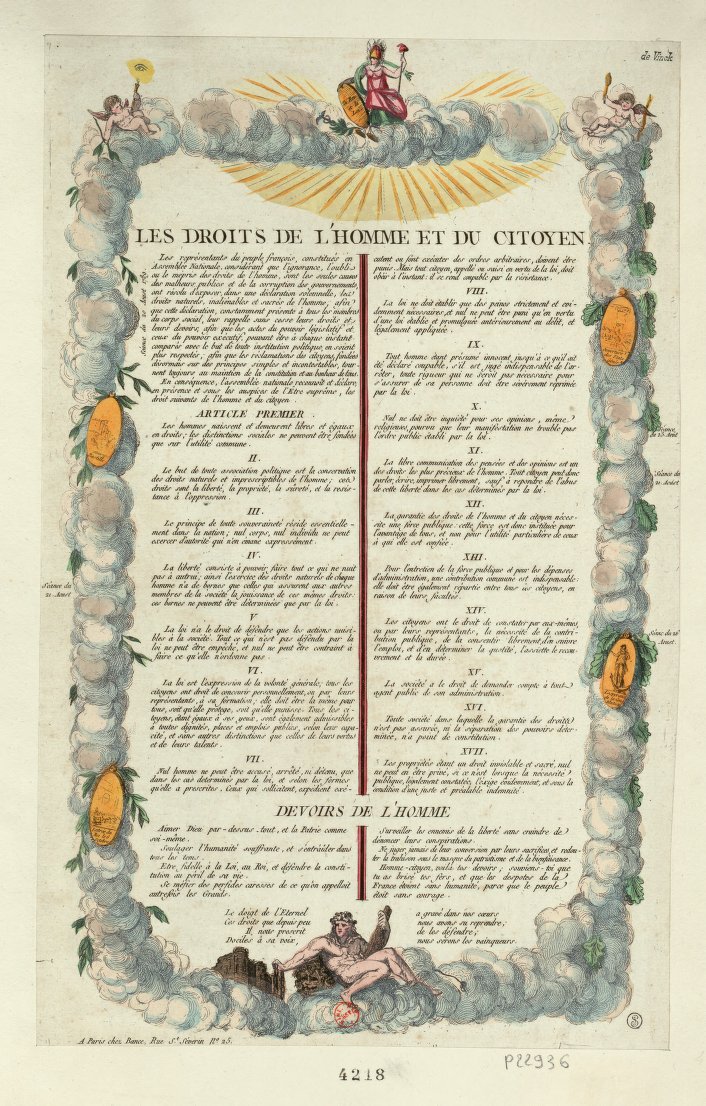

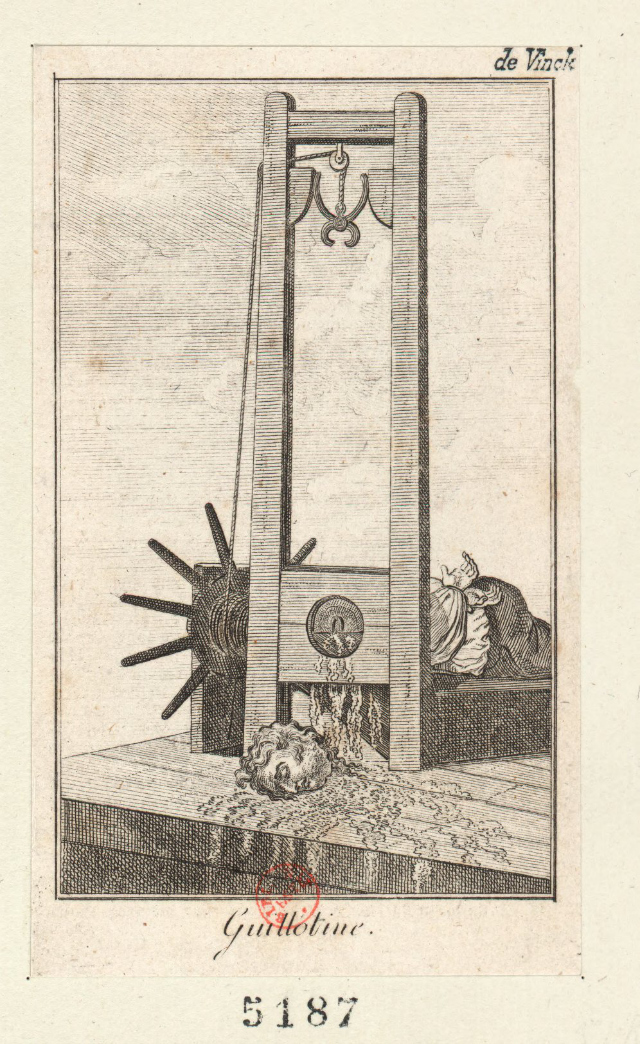

This past December, we wrote about the British Library’s releasing “over a million images onto Flickr Commons for anyone to use, remix and repurpose.” For those who enjoyed this treasure trove of historical content, we bring more good tidings: the British Library also has a freely accessible online gallery, numbering some 30,000 items.

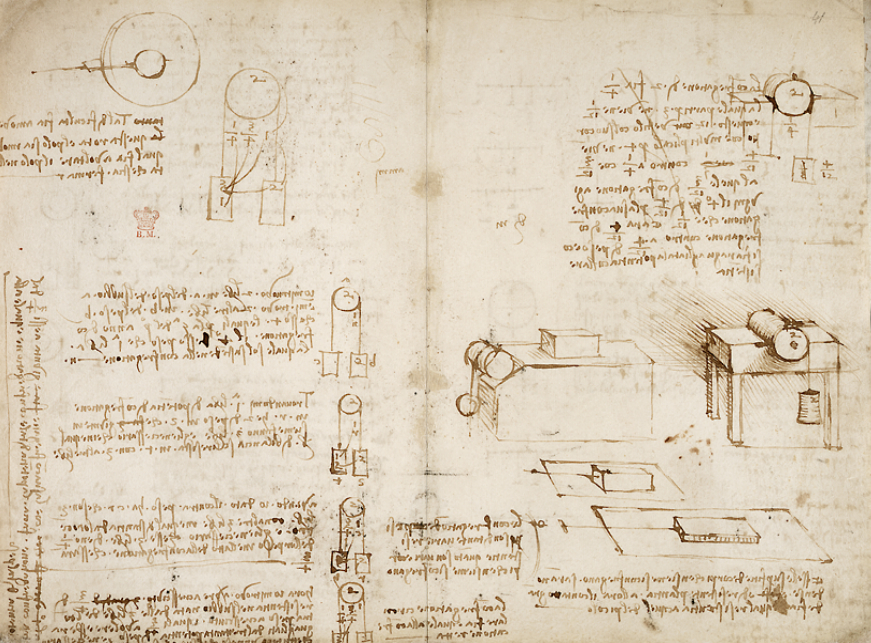

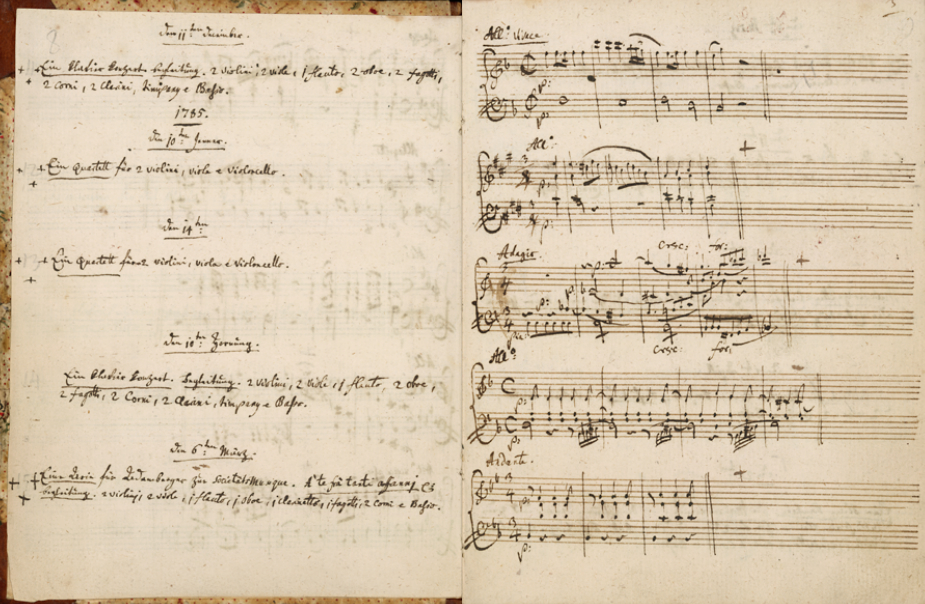

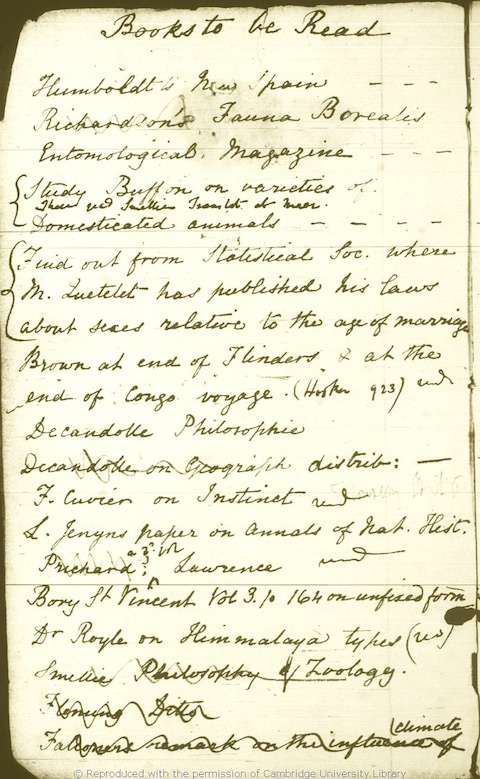

The vast digital collection includes books, ancient maps, and priceless prints. Amid the countless virtual tomes, some of the more impressive holdings include Mozart’s musical diary from the last seven years of his life, and Leonardo da Vinci’s notebook (find both above) where the artist and inventor theorized about mechanics. Da Vinci also recorded riddles in his notes, including: “The dead will come from underground and by their fierce movements will send numberless human beings out of the world” (Answer: “Iron, which comes from under the ground, is dead, but the weapons are made of it which kill so many men”).

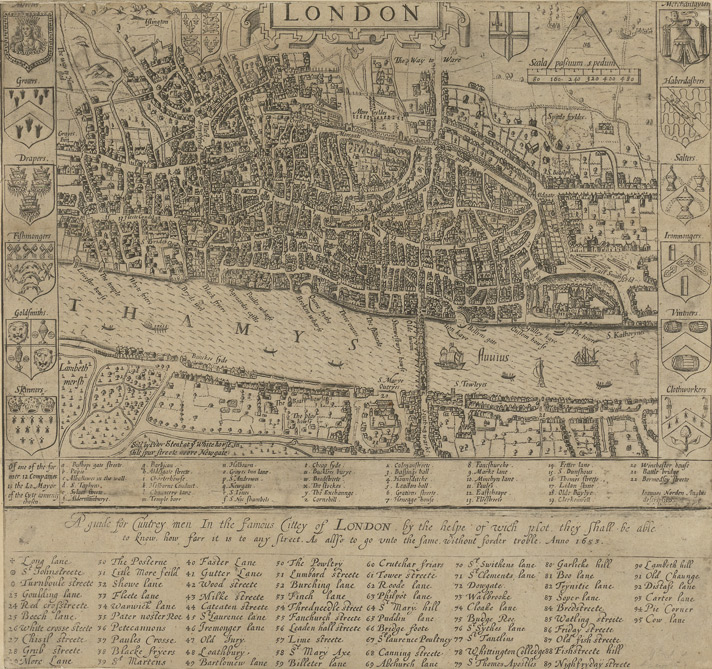

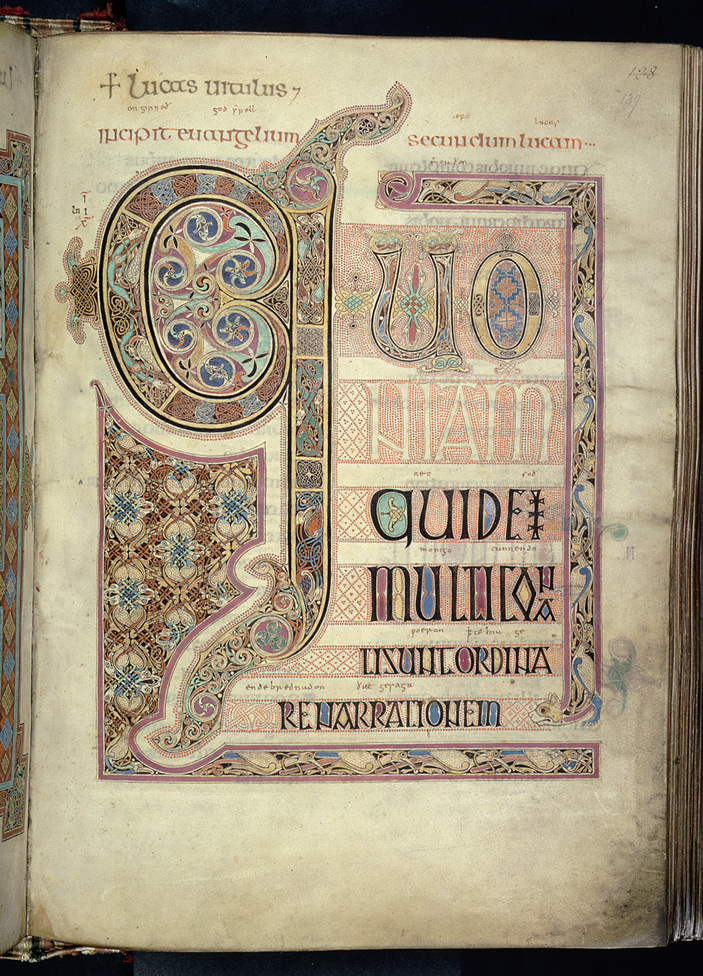

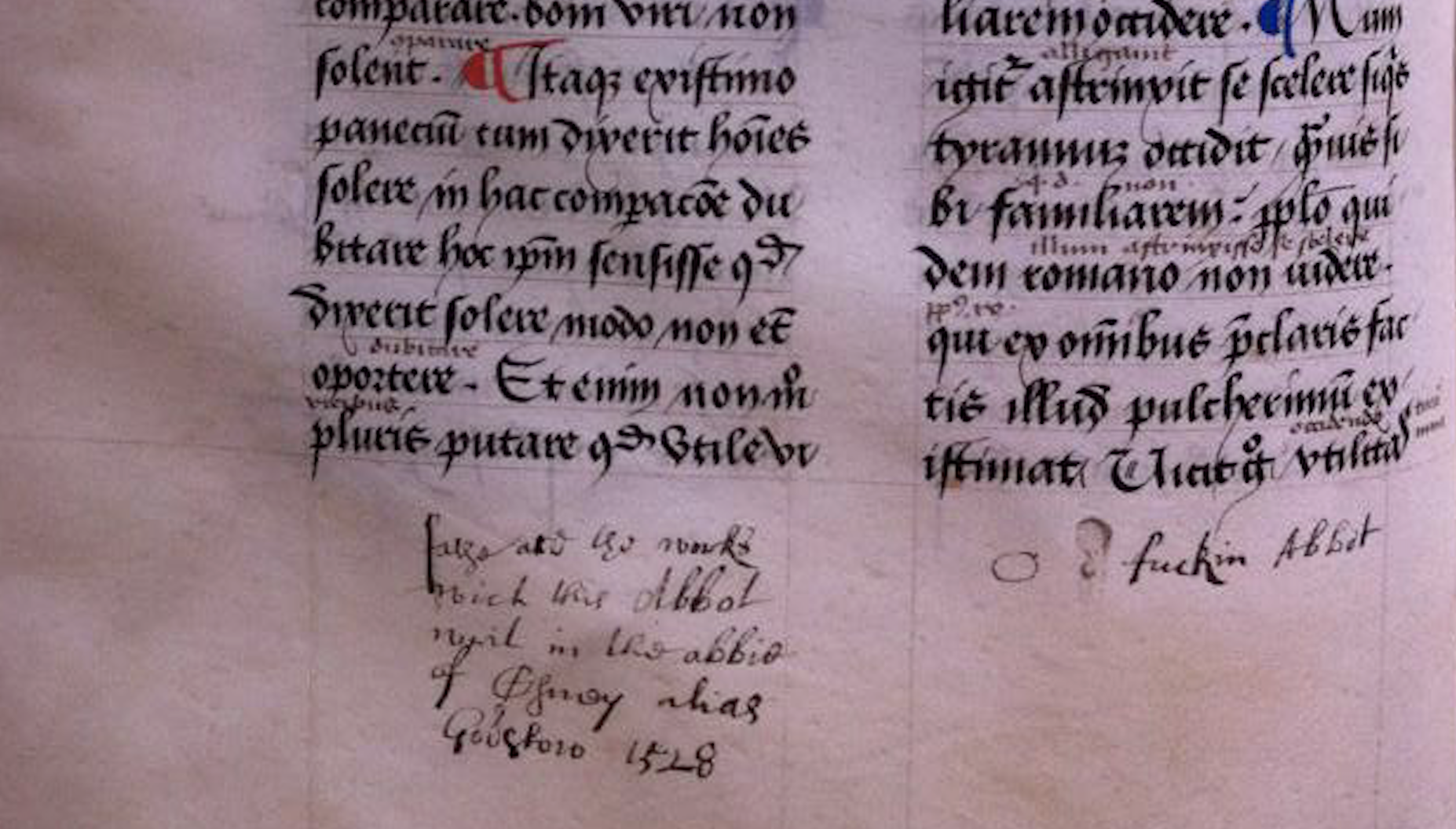

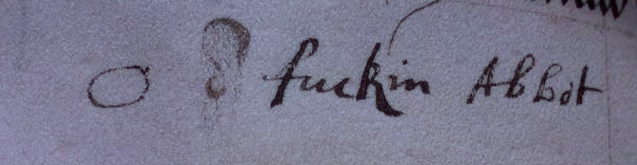

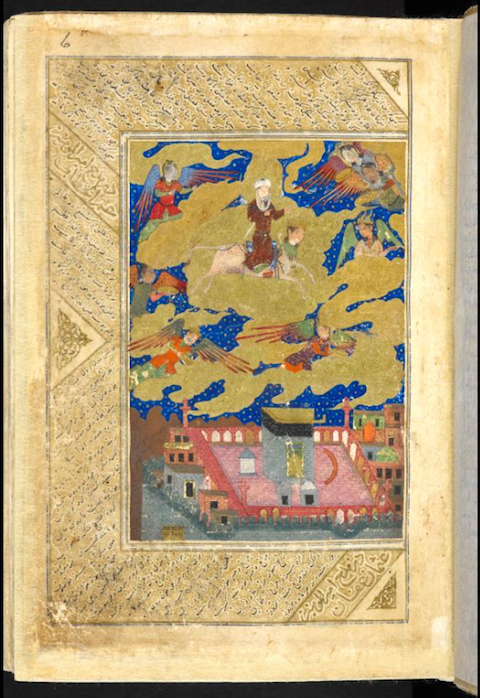

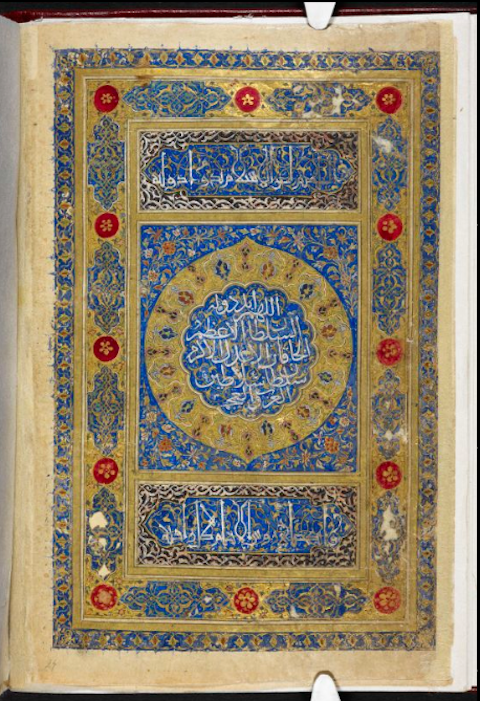

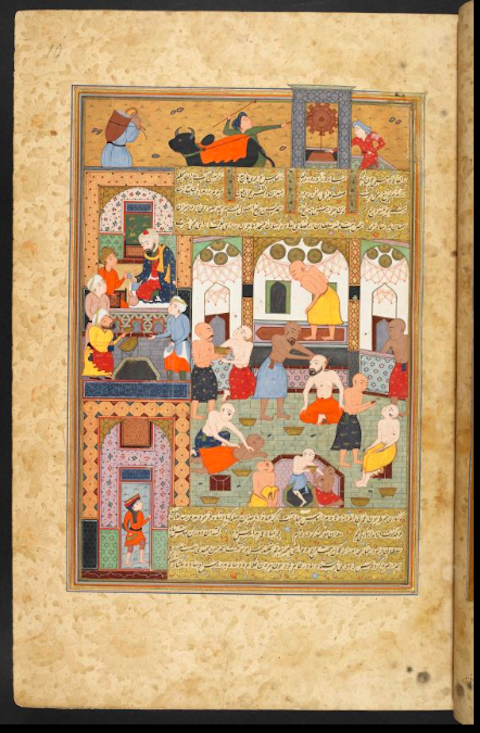

The online collection also contains a number of expertly curated exhibits by British Library staff, many of which are accompanied by a thorough introduction to guide readers through the material. I’ve always liked getting lost in old, detailed maps and particularly enjoyed the Crace Collection of Maps of London, which range from a 16th century “guide for cuntrey men in the famous cittey of London by the helpe of wich plot they shall be able to know how far it is to any street,” to a 19th century puzzle-type map, whose readers must find a particular route from the Strand to St. Paul’s. The collection also contains a terrific selection of pre-printing-press-era illuminated manuscripts, deemed “illuminated” because they were meticulously decorated, often using gold leaf. Among these are the opening of St. Luke’s Gospel from the Lindisfarne Bible (below), one of the earliest surviving English language Gospels (circa 715 CE), and scenes from the life of St. Guthlac, which dates to the early 13th century.

For more of the British Library’s Online Collection, head here.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman, or read more of his writing at the Huffington Post.

Related Content:

The Getty Puts 4600 Art Images Into the Public Domain (and There’s More to Come)

The National Gallery Makes 25,000 Images of Artwork Freely Available Online