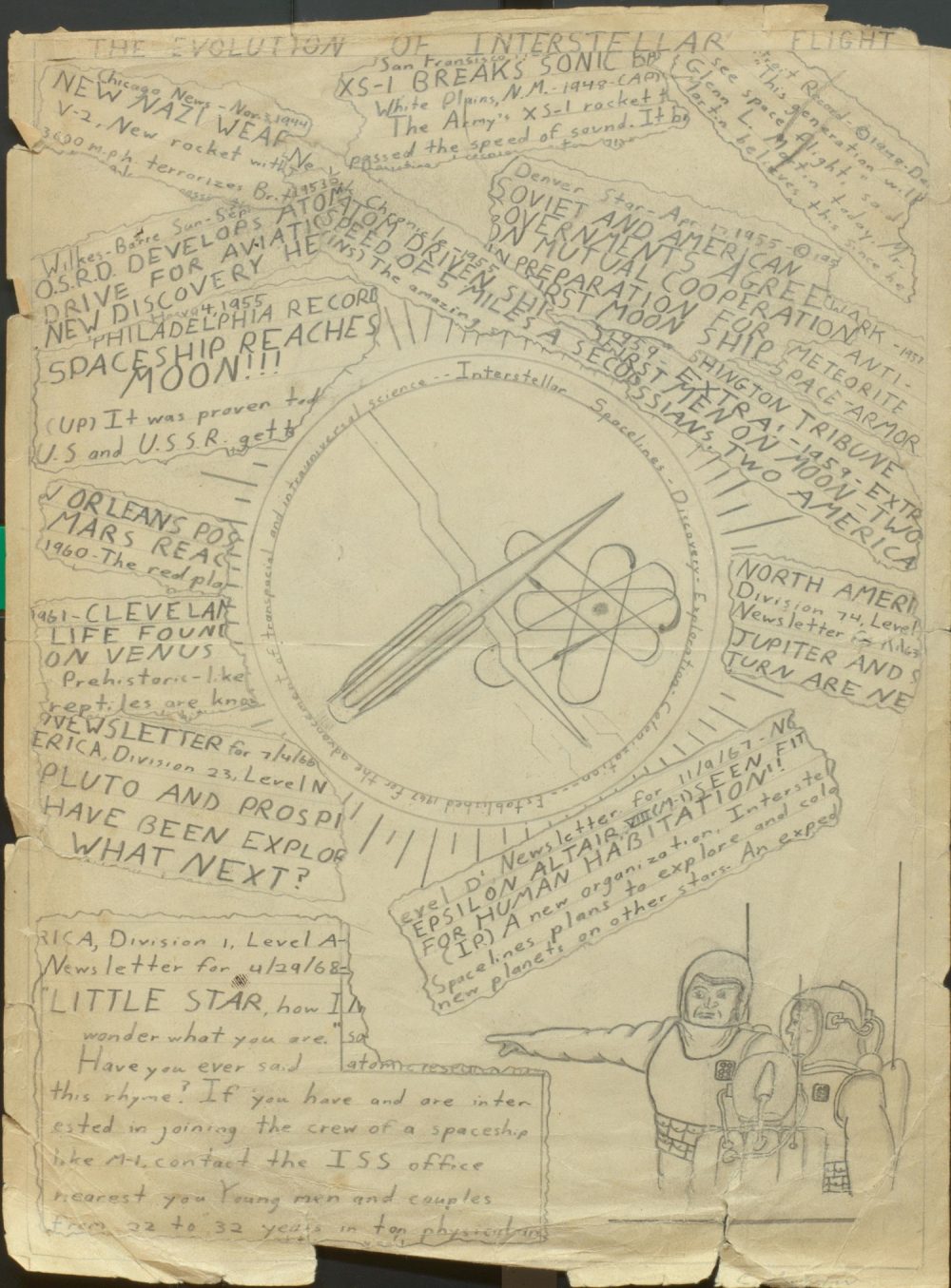

Several days ago, we brought you a rare Carl Sagan sketch, where the young scientist depicted an imagined history of interstellar space flight. In that post, we made brief mention of the Seth MacFarlane Collection of the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive, which merits to be highlighted in its own right: its arrival means that the Internet now has access to a vast repository of the eminent science educator’s original papers and personal artifacts.

Historians, biographers, and die-hard Sagan devotees will inevitably want to visit the Library of Congress in person to view the full archive, which contains over 1700 boxes of material. The lay reader curious about Sagan’s life, however, won’t need to make the trek to the U.S. capital to sample the archive’s contents. That’s because the Library of Congress has uploaded a portion of the collection online, including sundry fascinating biographical pieces. Above, you can view a digitized set of the Sagan family’s silent home movies, where young Carl shows off his boyhood boxing prowess, rides horseback, and plays piano (preciously, we presume).

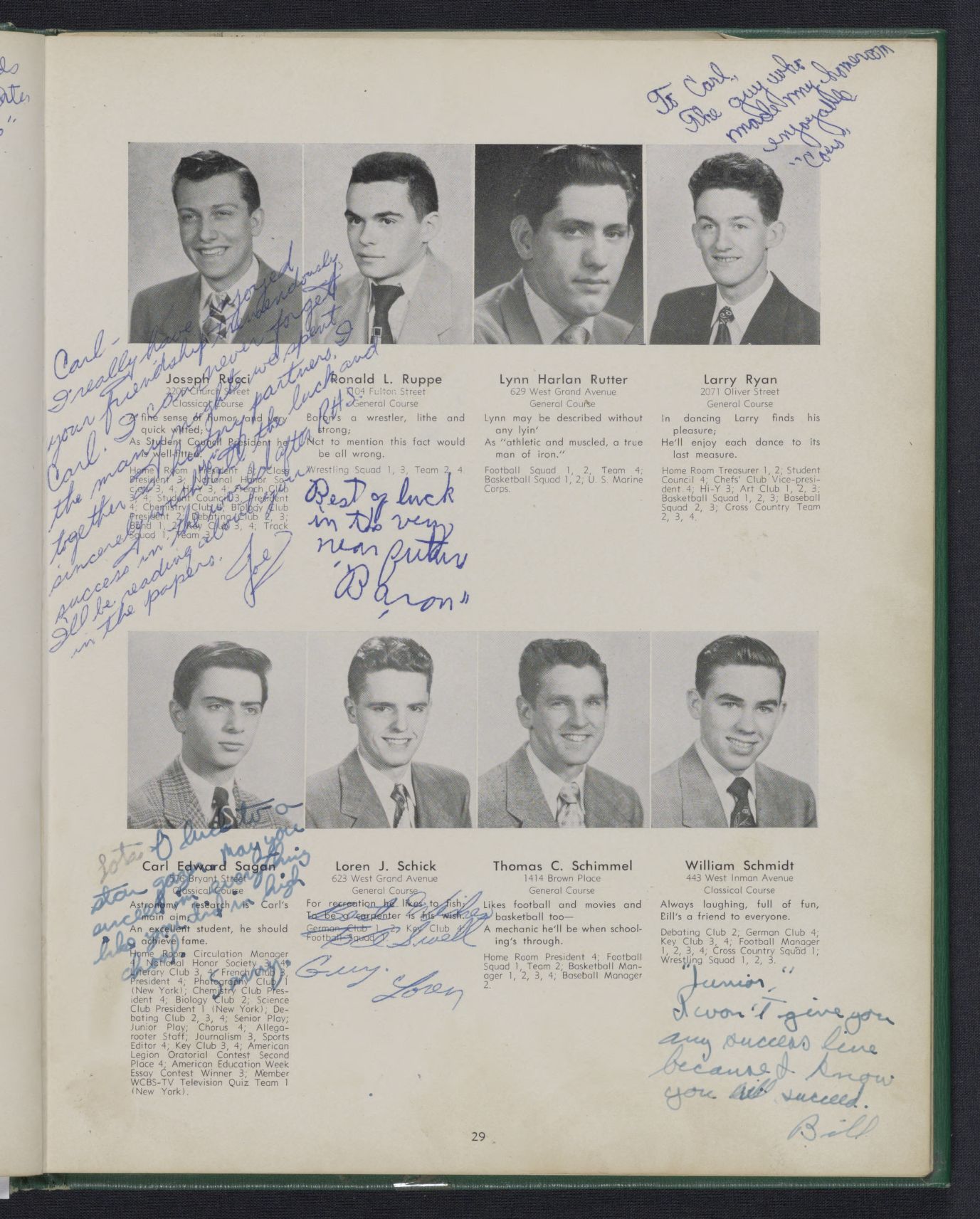

It was during high school that Sagan began to fill out intellectually. His senior yearbook is testimony to both his interest in science and the humanities: not only was Sagan president of both the science and chemistry clubs, he also led the French club, served as an editor on his school’s newspaper, debated, took part in theatre productions, and was a member of the photography club.

Indeed, Sagan displayed his uncanny ability to merge science with the humanities in Wawawhack, his high school newspaper, writing a piece entitled “Space, Time, and The Poet.” He begins by saying, “it is an exhilarating experience to read poetry and observe its correlation with modern science. Profound scientific thought is hardly a rarity among the poets.” Throughout the piece, Sagan goes on to draw from verses by Alfred Lord Tennyson, T. S. Eliot, John Milton, and Robert Frost.

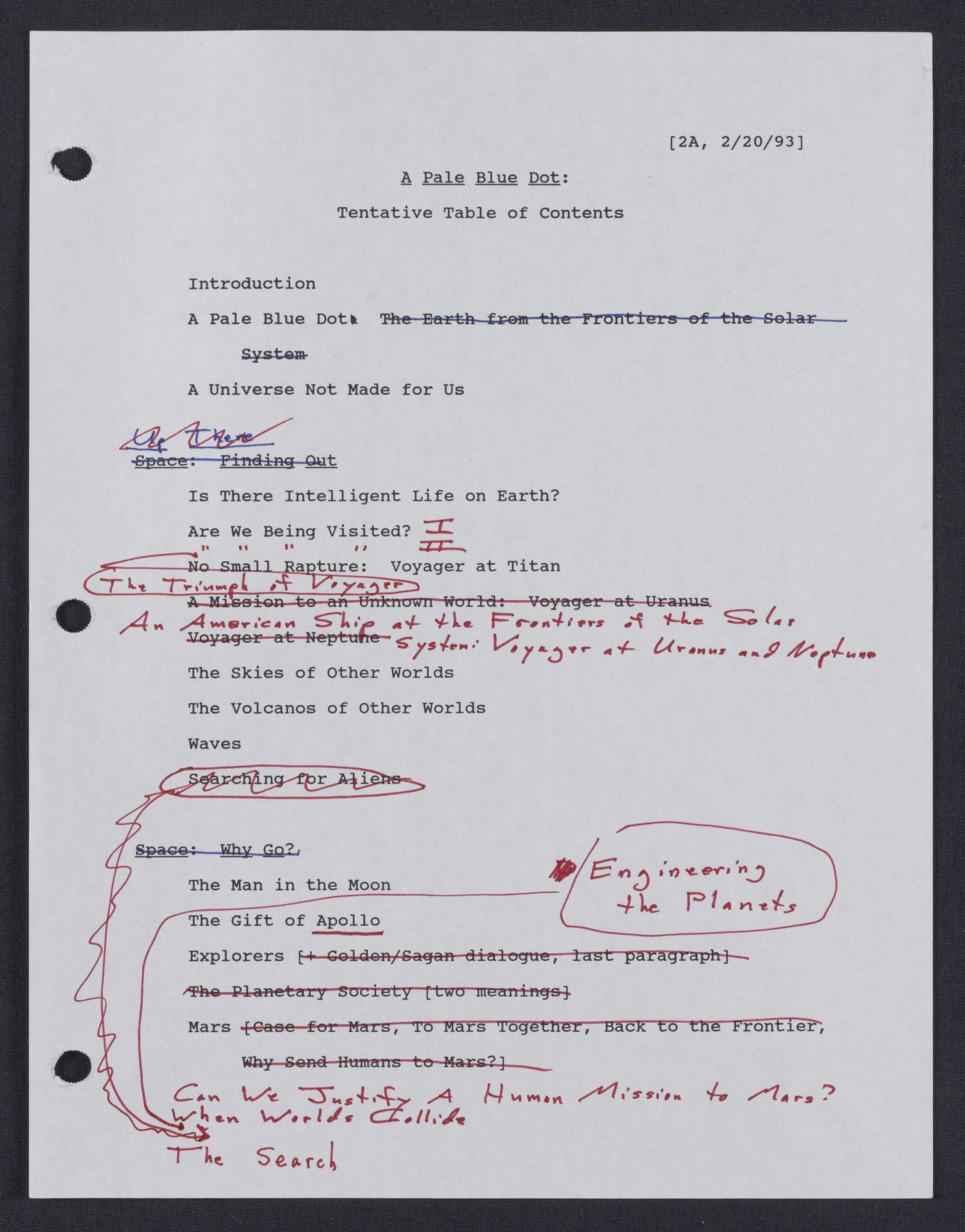

Mixing science and literature would remain one of Sagan’s specialties, and would eventually lead to his writing The Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of Human Future In Space (1994). The book discusses humankind’s place in the universe, past, present, and future, and a PDF version of the annotated second draft, pictured below, is available in the archive.

For more of the digitized collection, visit Seth MacFarlane Collection of the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive.

via Boing Boing

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Carl Sagan’s Undergrad Reading List: 40 Essential Texts for a Well-Rounded Thinker

Carl Sagan, Stephen Hawking & Arthur C. Clarke Discuss God, the Universe, and Everything Else