Italy is widely celebrated for having vigilantly preserved its food culture, with the result that many dishes there are still prepared in more or less the same way they have been for centuries. When you taste Italian food at its best, you taste history — to borrow the name of a Youtube channel whose success has revealed a surprisingly widespread enthusiasm for the cuisine of bygone eras. But some of Italy’s most globally beloved comestibles aren’t quite as deeply rooted in the past as people tend to assume: there are no records of tiramisu, for instance, before the nineteen-sixties; ciabatta, the Italian answer to the baguette, was invented in the early nineteen-eighties.

Neither of them appear anywhere in Historical Italian Cooking, a bilingual blog in English and Italian that teaches how to partake in far more venerable culinary traditions. A variety of periods are represented: the nineteenth century (Neapolitan calamari, tagliatelle and beef stew), the Renaissance (crostini with guanciale and sage, elderflowers fritters), the Middle Ages (monk’s stuffed-egg soup, quails with sumac), and even the time of ancient Rome (cuttlefish cakes, Horace’s lagana and chickpeas).

You can also see these and other dishes prepared on Historical Italian Cooking’s Youtube channel, which offers playlists organized by era, region, and chief ingredient: Medieval Tuscan recipes, ancient fish recipes, early medieval recipes at the court of the Franks.

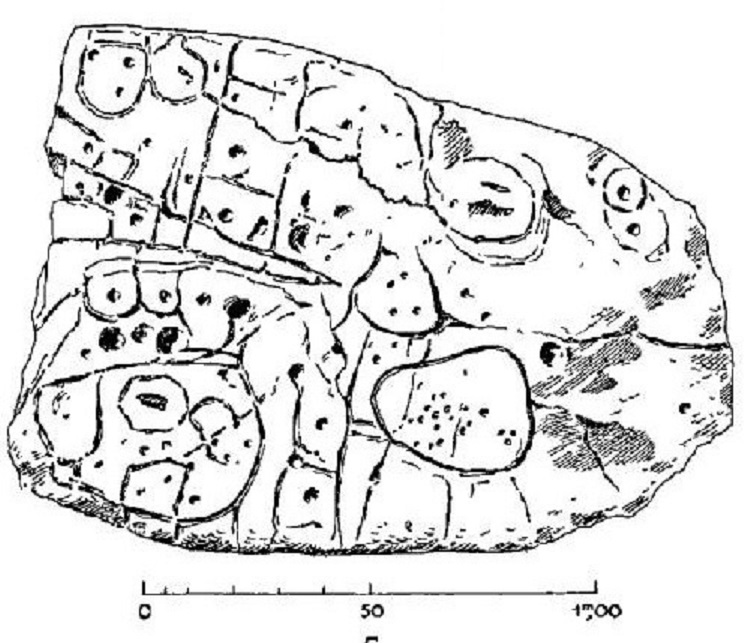

Historical Italian Cooking’s most popular video shows every step involved in making “the most famous ancient Mediterranean sauce, garum.” The recipe comes straight from De Re Coquinaria, the oldest known cookbook in existence, which we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture. If you’d like to try your hand at making this bold condiment, make sure you’ve got the time: you’ll have to let the fish it’s made of it sit for at least a few days, stirring it three or four times per day, though some recipes suggest continuing this process for three or four months before the garum is ready to eat. If, on further consideration, you’d prefer to make a pizza, Historical Italian Cooking can help with that as well: just make sure you’ve got enough lard and quails.

Related content:

A Free Course from MIT Teaches You How to Speak Italian & Cook Italian Food All at Once

The Futurist Cookbook (1930) Tried to Turn Italian Cuisine into Modern Art

When Italian Futurists Declared War on Pasta (1930)

Explore the Roman Cookbook, De Re Coquinaria, the Oldest Known Cookbook in Existence

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.