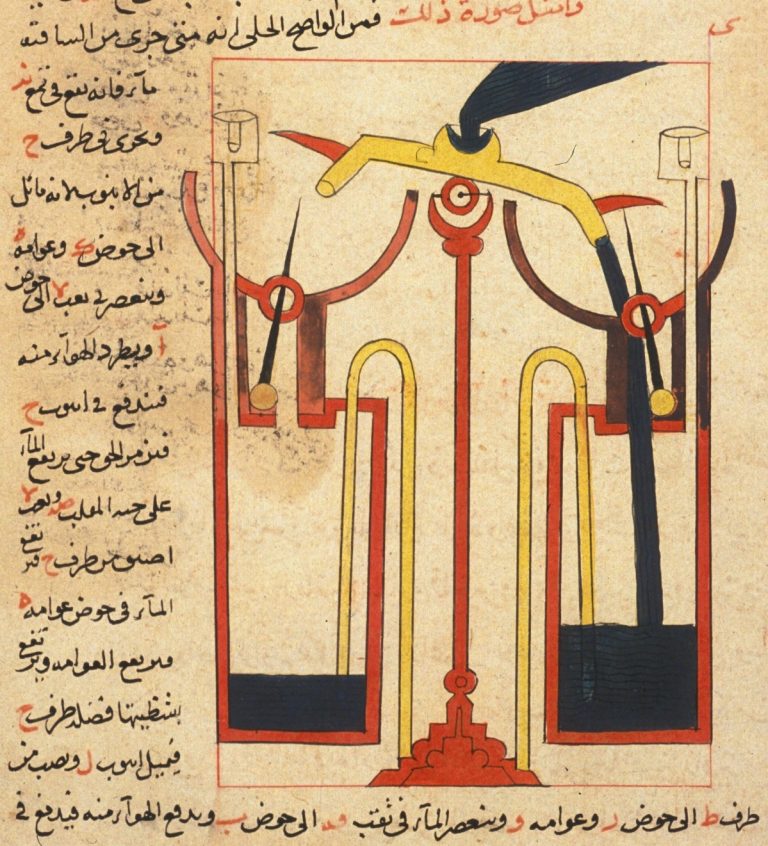

“Enable subtitles,” says the notification that appears before The Poor Man of Nippur — and you will need them, unless, of course, you happen to hail from the cradle of civilization. The short film is adapted from “a folktale based on a 2,700-year-old poem about a pauper,” says the University of Cambridge’s alumni news, acted out word-for-word by “Assyriology students and other members of the Mesopotamian community at the University.” The result qualifies as the world’s very first film in Babylonian, a language that has “been silent for 2,000 years.”

“Found on a clay tablet at the archaeological site of Sultantepe, in south-east Turkey,” the story of The Poor Man of Nippur hasn’t come down to us in perfectly complete form. The film represents the points of breakage in the tablet with VHS-style glitches, a neat parallel of forms of media degradation across the millennia.

That isn’t the only noticeable anachronism — taking the buildings of Cambridge for Mesopotamia in the seventh century BC demands a certain suspension of disbelief — but we can rest assured of the Babylonian dialogue’s historical accuracy, or at least that this is the most accurate Babylonian dialogue we’re likely to get.

According to Cambridge Assyriologist Martin Worthington, who oversaw the Poor Man of Nippur project (after serving as Babylonian consultant for The Eternals), determining its pronunciation involves “a mix of educated guesswork and careful reconstruction,” but one that benefits from existing “transcriptions into the Greek alphabet” as well as connections with stabler languages like Arabic and Hebrew. The result is an unprecedented historical-linguistic attraction, a compelling advertisement for the study of Babylonian at Cambridge, and also — in depicting the impoverished protagonist’s revenge on a thuggish town mayor — a demonstration that the underdog story transcends time, culture, and language.

Related content:

Listen to The Epic of Gilgamesh Being Read in its Original Ancient Language, Akkadian

Listen to the Oldest Song in the World: A Sumerian Hymn Written 3,400 Years Ago

Trigonometry Discovered on a 3700-Year-Old Ancient Babylonian Tablet

Learn Latin, Old English, Sanskrit, Classical Greek & Other Ancient Languages in 10 Lessons

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.