For better (I’d say), or worse, the internet has turned cat people into what may be the world’s most powerful animal lobby. It has brought us fascinating animated histories of cats and animated stories about the cats of gothic genius and cat-loving author and illustrator Edward Gorey; cats blithely leaving inky pawprints on medieval manuscripts and politely but firmly refusing to be denied entry into a Japanese art museum. It has given us no shortage of delightful photos of artists with their cat familiars…

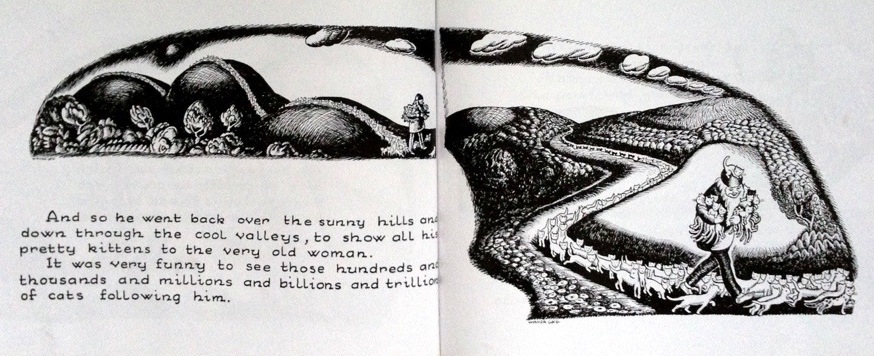

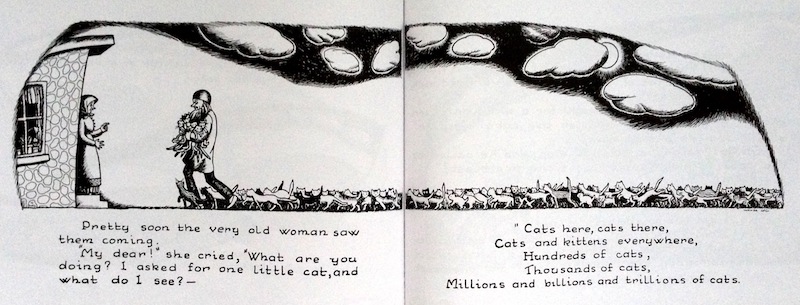

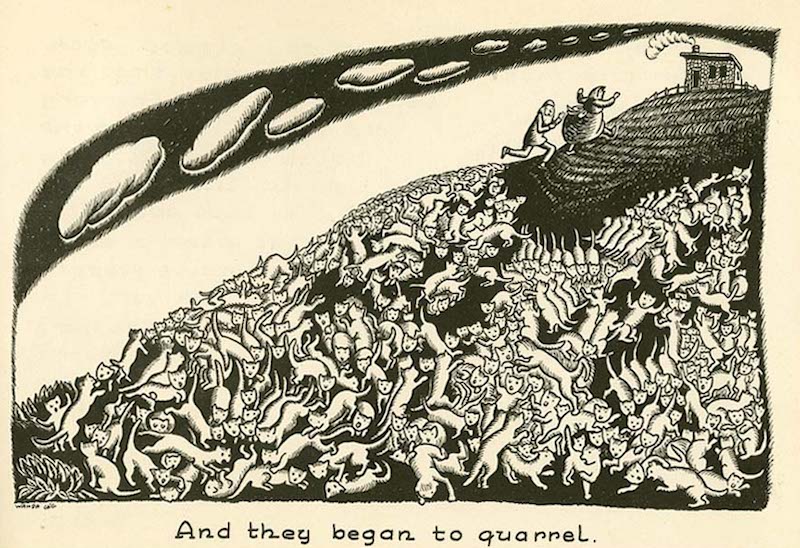

Cat antics and awe have always been a very online phenomenon, but the mysterious and ridiculous, diminutive beasts of prey have also always been inseparable from art and culture. As further evidence, we bring you Millions of Cats, likely the “first truly American picture book done by an American author/artist,” explains a site devoted to it.

“Prior to its publication in 1928, there were only English picture books for the children’s perusal.” The book “sky rocketed Wanda Gág into instant fame and set in stone her reputation as a children’s author and illustrator.”

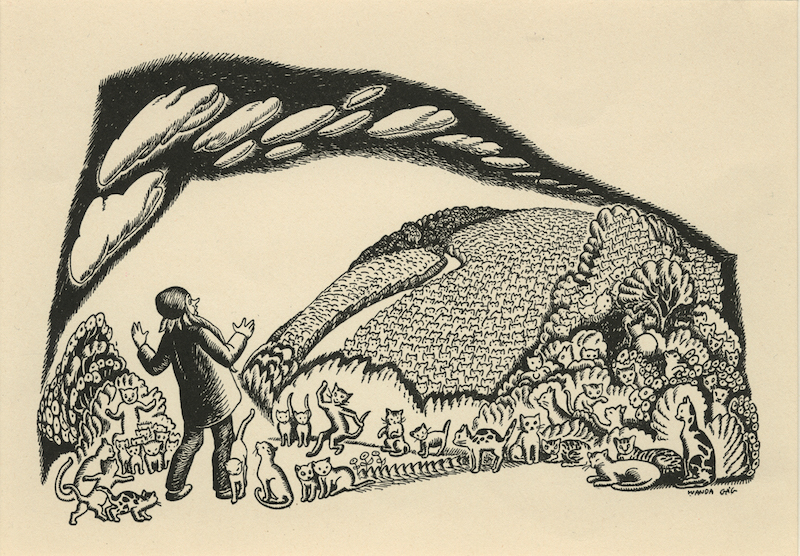

It set a standard for Caldecott-winning children’s literature for close to a hundred years since its appearance, though the award did not yet exist at the time. The book’s creator was “a fierce idealist and did not believe in altering her own aestheticism just because she was producing work for children. She liked to use stylized human figures, asymmetrical compositions, strong lines and slight spatial distortion.” She also loved cats, as befits an artist of her independent temperament, one shared by the likes of other cat-loving artists like T.S. Eliot and Charles Dickens.

Millions of Cats’ author and illustrator may not share in the fame of so many other artists who took pictures with their cats, but she and her cat Noopy were as photogenic as any other feline/human artistic duo, and she was a peer to the best of them. The book’s editor, Ernestine Evans, wrote in the Nation that Millions of Cats “is as important as the librarians say it is. Not only does it bring to book-making one of the most talented and original of American lithographers… but it is a marriage of picture and tale that is perfectly balanced.”

Gág (rhymes with “jog”) was “a celebrated artist… in the Greenwich Village-centic Modernist art scene in the 1920s,” writes Lithub, “a free-thinking, sex-positive leftist who also designed her own clothes and translated fairy tales.” She adapted the text from “a story she had made up to entertain her friends’ children,” with the millions of cats modeled on Noopy. Gág is the founding mother of children’s book dynasties like The Cat in the Hat and Pete the Cat, an artist whom millions of cat lovers can discover again or for the first time in a Newbery-winning 2006 collector’s edition.

Read a summary of the charming story of Millions of Cats at Lithub and learn more about her, the talented Gág family of artists, and her charming, very cat-friendly house here.

Related Content:

Insanely Cute Cat Commercials from Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki’s Legendary Animation Shop

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

A Digital Archive of 1,800+ Children’s Books from UCLA

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness