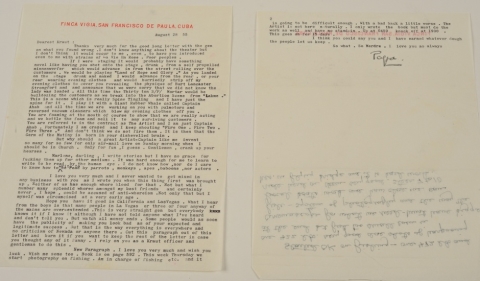

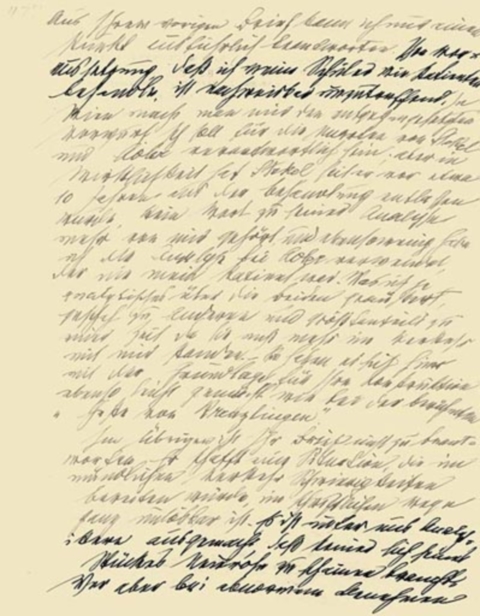

Freud and Jung. Jung and Freud. History has closely associated these two who did so much examination of the mind in early 20th-century Europe, but the simple connection of their names belies a much more complicated relationship between the men themselves. At the top of the post, you can see the letter that Sigmund Freud, father of psychoanalysis, wrote to Carl Gustav Jung, founder of analytical psychology, in order to end that relationship entirely. “At first Freud saw in Jung a successor who might lead the psychoanalytic movement into the future,” say the curator’s comments at the Library of Congress’ web site, “but by 1913 relations between the two men had soured.

While Freud claims in his letter that it is ‘demonstrably untrue’ that he treats his followers as patients, in the very same letter we find him alluding to Jung’s ‘illness.’ ” Freud calls it “a convention among us analysts that none of us need feel ashamed of his own neurosis. But one [meaning Jung] who while behaving abnormally keeps shouting that he is normal gives ground for the suspicion that he lacks insight into his illness. Accordingly, I propose that we abandon our personal relations entirely.”

“I shall lose nothing by it,” he continues, “for my only emotional tie with you has been a long thin thread — the lingering effect of past disappointments — and you have everything to gain, in view of the remark you recently made to the effect that an intimate relationship with a man inhibited your scientific freedom.” This relationship, writes Lionel Trilling in a review of The Correspondence Between Sigmund Freud and C.G. Jung, “had its bright beginning in 1906 and came to its embittered end in 1913,” when Freud wrote this letter. “Freud and Jung were not good for one another; their connection made them susceptible to false attitudes and ambiguous tones. [ … ] The intellectual and professional differences between the two men, profound as these eventually became, would perhaps not of themselves have brought about a break so drastic as did take place had not their alienating tendency been reinforced by personal conflicts.” Only a comparative study of Freud and Jung’s methods would yield a complete understanding of their roles in the struggle for the soul of psychoanalysis. But on a more basic level, this hardly counts as the first nor the last collapse, in any field of human endeavor, of a perhaps overdetermined succession between an eminence and his would-be protege — though it may count as one of the most eloquently documented ones.

Related Content:

Sigmund Freud Speaks: The Only Known Recording of His Voice, 1938

Face to Face with Carl Jung: ‘Man Cannot Stand a Meaningless Life’

Carl Gustav Jung Ponders Death

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.