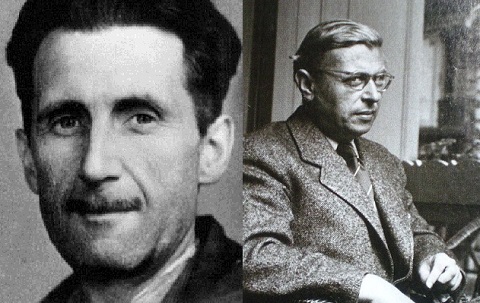

Yesterday we featured George Orwell’s review of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf — not just an isolated newspaper piece, or one of a scattered few, in a life otherwise spent churning out important novels like Animal Farm and 1984, but a particularly perceptive book review among the many in his prolific journalistic career. (He even wrote “Confessions of a Book Reviewer,” the definitive article on that practice.) Today we have another of Orwell’s pieces taking on a well-known 20th-century Continental figure: this time, the French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and his book Portrait of the Antisemite.

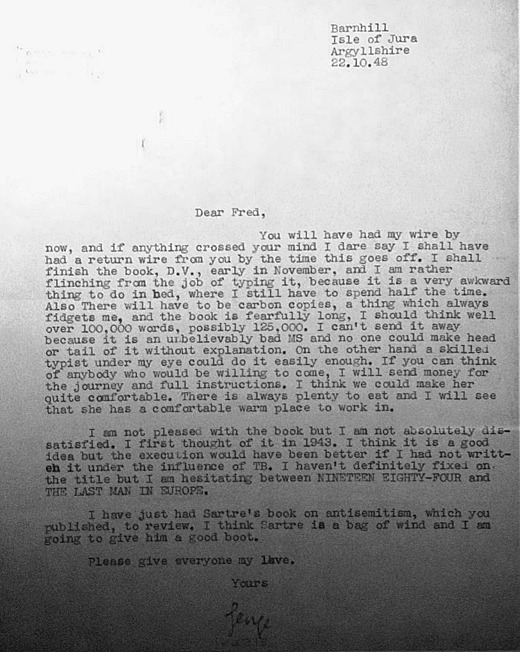

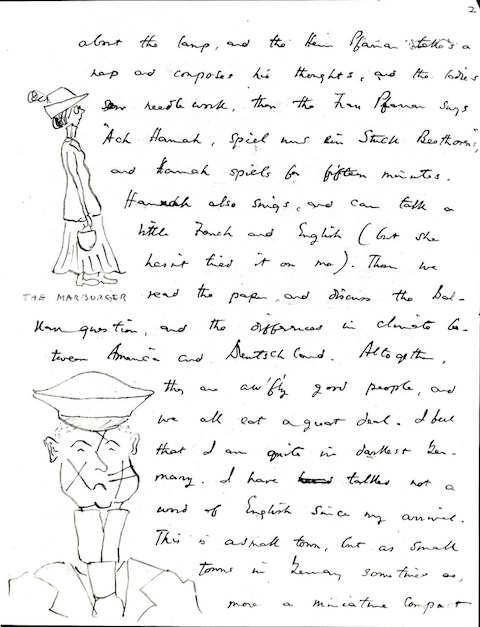

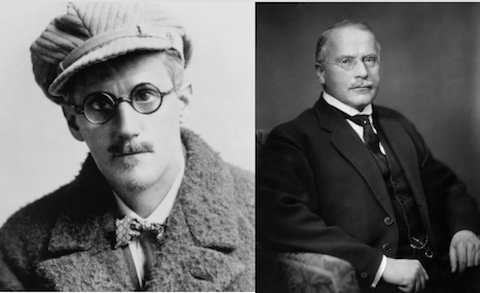

But as a prelude to the review, have a look at the October 1948 letter above, posted originally at Letters of Note. In it, Orwell writes to his publisher Frederic Warburg, keeping him posted on the state of the manuscript of 1984. Then, at the very end, he adds that “I have just had Sartre’s book on antisemitism, which you published, to review. I think Sartre is a bag of wind and I am going to give him a good boot.” That “good boot,” which ran in The Observer the next month, goes like this:

Antisemitism is obviously a subject that needs serious study, but it seems unlikely that it will get it in the near future. The trouble is that so long as antisemitism is regarded simply as a disgraceful aberration, almost a crime, anyone literate enough to have heard the word will naturally claim to be immune from it; with the result that books on antisemitism tend to be mere exercises in casting motes out of other people’s eyes. M. Sartre’s book is no exception, and it is probably no better for having been written in 1944, in the uneasy, self-justifying, quisling-hunting period that followed on the Liberation.

At the beginning, M. Sartre informs us that antisemitism has no rational basis: at the end, that it will not exist in a classless society, and that in the meantime it can perhaps be combated to some extent by education and propaganda. These conclusions would hardly be worth stating for their own sake, and in between them there is, in spite of much cerebration, little real discussion of the subject, and no factual evidence worth mentioning.

We are solemnly informed that antisemitism is almost unknown among the working class. It is a malady of the bourgeoisie, and, above all, of that goat upon whom all our sins are laid, the “petty bourgeois.” Within the bourgeoisie it is seldom found among scientists and engineers. It is a peculiarity of people who think of nationality in terms of inherited culture and property in terms of land.

Why these people should pick on Jews rather than some other victim M. Sartre does not discuss, except, in one place, by putting forward the ancient and very dubious theory that the Jews are hated because they are supposed to have been responsible for the Crucifixion. He makes no attempt to relate antisemitism to such obviously allied phenomena as for instance, colour prejudice.

Part of what is wrong with M. Sartre’s approach is indicated by his title. “The” anti-Semite, he seems to imply all through the book, is always the same kind of person, recognizable at a glance and, so to speak, in action the whole time. Actually one has only to use a little observation to see that antisemitism is extremely widespread, is not confined to any one class, and, above all, in any but the worst cases, is intermittent.

But these facts would not square with M. Sartre’s atomised vision of society. There is, he comes near to saying, no such thing as a human being, there are only different categories of men, such as “the” worker and “the” bourgeois, all classifiable in much the same way as insects. Another of these insect-like creatures is “the” Jew, who, it seems, can usually be distinguished by his physical appearance. It is true that there are two kinds of Jew, the “Authentic Jew,” who wants to remain Jewish, and the “Inauthentic Jew,” who would like to be assimilated; but a Jew, of whichever variety, is not just another human being. He is wrong, at this stage of history, if he tries to assimilate himself, and we are wrong if we try to ignore his racial origin. He should be accepted into the national community, not as an ordinary Englishman, Frenchman, or whatever it may be, but as a Jew.

It will be seen that this position is itself dangerously close to anti-semitism. Race prejudice of any kind is a neurosis, and it is doubtful whether argument can either increase or diminish it, but the net effect of books of this kind, if they have an effect, is probably to make antisemitism slightly more prevalent than it was before. The first step towards serious study of antisemitism is to stop regarding it as a crime. Meanwhile, the less talk there is about “the” Jew or “the” antisemite, as a species of animal different from ourselves, the better.

In Philosophy Now, Martin Tyrrell writes on Orwell’s relationship to the subject, which he saw “as a kind of gratuitous cleverness and he had no appetite for that. In Orwell’s writings, fiction or non-fiction, there are few good intellectuals. Where they appear, then it is usually only to spin words without meaning. At best, they are inadvertently confusing; at worst, deliberately so: Marxists, for example, or nationalists or Anglo or Roman Catholics. Or Jean-Paul Sartre. [ … ] Bewildered by existentialism, what most irked Orwell about Sartre was his seeming denial of individuality.” Tyrrell describes Orwell as “an individualist so much so that, when he came to list his reasons for becoming a writer, he put ‘sheer egoism’ at the top. In addition, and much more controversially, his review of Mein Kampf sees in Hitler more than a little of the tragic Orwellian hero, the small man embarked upon a doomed revolt.” Not everyone, of course, will agree with Orwell’s aggressively plainspoken takes on Hitler and Nazism, or Sartre and existentialism, but try substituting a variety of other controversial “-isms” for “antisemitism” in the review above, and you’ll see how we’d still think more clearly if we bore his observations in mind today.

via Letters of Note

Related Content:

George Orwell Reviews Mein Kampf (1940)

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

George Orwell’s 1984: Free eBook, Audio Book & Study Resources

Jean-Paul Sartre Breaks Down the Bad Faith of Intellectuals

Sartre, Heidegger, Nietzsche: Documentary Presents Three Philosophers in Three Hours

Walter Kaufmann’s Classic Lectures on Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Sartre (1960)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.